The Bizarre (and Magical) Duel Between Chung Ling Soo and Ching Ling Foo

While performing at the Wood Green Empire in London in 1918, one of the most famous and successful magicians in the world, Chinese illusionist Chung Ling Soo, was unfortunately killed attempting to catch a bullet. The fact that he got shot was only part of what astonished the audience that day. You see, directly after, Soo- a man who’d spent his entire career working in silence or through translators, and long claimed he understood no language except Chinese- exclaimed in perfect English, “I’ve been shot! Bring down the curtain!”

While performing at the Wood Green Empire in London in 1918, one of the most famous and successful magicians in the world, Chinese illusionist Chung Ling Soo, was unfortunately killed attempting to catch a bullet. The fact that he got shot was only part of what astonished the audience that day. You see, directly after, Soo- a man who’d spent his entire career working in silence or through translators, and long claimed he understood no language except Chinese- exclaimed in perfect English, “I’ve been shot! Bring down the curtain!”

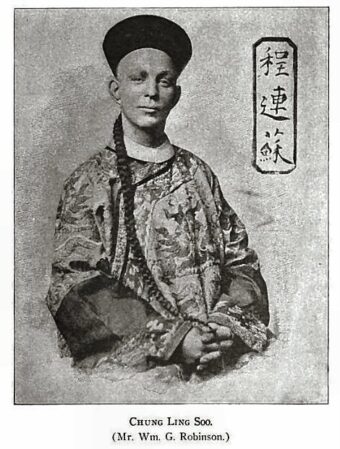

As it turns out, Chung Ling Soo wasn’t a Chinese illusionist at all, but an American man who’d lifted his entire gimmick wholesale from an actual Chinese magician and somehow had gotten away with it for nearly two decades. If that wasn’t impressive enough, at one point he even convinced the general public that the man he copied was the actual imposter, seeing said individual, Chinese magician Ching Ling Foo, more or less disappear from the history books after. This is the bizarre story of Chung Lin Soo, or as his parents named him- William Ellsworth Robinson.

Born in Westchester County, New York in 1861, Robinson was fascinated by magic from a young age and his studious nature eventually saw him becoming proficient in a number of magical skills by his early teens. By age 14, Robinson was sufficiently adept at the magical arts to work as a performer on the vaudeville circuit, earning a decent living with his illusions and tricks. A consummate performer of magic by all accounts, Robinson’s weakness was his stage persona, with the magician being said to lack the, shall we say, razzmatazz of a seasoned magician or illusionist. Robinson attempted to address this by billing himself as “Robinson, the man of mystery” but still found himself unable to land the headlining role in any vaudeville show due to his near total lack of charisma or charm.

Frustrated, in what would become his modus operandi later in life, he thus decided to simply steal the gimmick of a better magician- specifically the German born magician Max Auzinger. Famous in his native German and throughout Europe, Auzinger regularly performed under the stage name “Ben Ali Bey”, and styled himself as a vaguely Asian occultist and master of the black arts. This more or less allowed Auzinger to have a bit of mystique about himself on stage, but without needing to talk. Robinson thus began billing himself as Ben Ali Bey sometime in 1887 and just copied the mostly silent act.

On that note, not content with just stealing the on stage persona Auzinger had spent his entire life crafting, Robinson also shamelessly lifted the German illusionists’ greatest trick- making objects seemingly appear from thin air. For anyone curious about how the trick was performed, Robinson would stand on a very dark and poorly lit stage wearing all white while an assistant covered in dark cloth would pull various objects out of their pockets and wave them around to make them look to those in the audience like they were flying.

Over the next few years, Robinson continued to style himself as a foreign illusionist and quietly developed his skills as a magician while opening for more famous magicians such as Harry Kellar and Alexander Herrmann. While studying under the former, he changed his act (and race) yet again when he heard the great magician lament that Egyptian mystics weren’t as impressive as Indian fakirs. Dutifully, Robinson altered his act and began billing himself as “Nana Sahib: The East Indian Necromancer”. Likewise, while studying under Hermann, Robinson learned that the magician favoured neither Egyptian nor Indian magic and was actually a fan of the illusions performed by conjurers in Constantinople. As a result, Nana Sahib became, Abdul Khan.

In each case, Robinson committed to the role as best he could, adopting the stereotypical garb and look associated with the culture he was trying to mimic, and invariably remaining wholly silent save for orders barked to assistants on-stage in broken English and his best attempt at an appropriate accent. Still, Robinson was unable to escape the shadows of the great illusionists he was opening for and found himself unable to secure a gig as a headlining act.

This all changed when the magician met Ching Ling Foo.

A master magician who’d been the personal illusionist to the Empress of China before travelling the world, Ching Ling Foo (real name, Zhu Liankui) first met Robinson in 1898 when the latter was still studying under Alexander Hermann. During this initial meeting, Robinson observed Hermann perform the Chinese linking rings trick to Foo as a demonstration of his skill and as a nod to China’s critical role in the development of magic as a performing art.

Foo reportedly walked away from this meeting unimpressed, and the next time the pair met, Foo is said to have performed a far more elaborate version of Hermann’s routine before throwing the rings aside and pulling a goldfish bowl out of thin air while breathing fire.

Naturally given all we’ve said about him so far, you’ll be unsurprised to learn that this all inspired Robinson to adopt an almost identical persona to that of Ching Ling Foo. Despite this, the feud between the two wouldn’t begin in earnest for another two years.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. To begin with, when Foo first arrived in the states to promote his act, he made a $1000 (about $31,000 today) standing bet with the entire American magical community that nobody would be able to replicate his most famous illusion- the water bowl trick.

In a nutshell, the trick would see Foo wave around a simple piece of cloth, from which he’d produce a comically large bowl of water. Foo would then place this bowl on a table which he’d then cover with the cloth before dramatically removing it to reveal the water had been replaced by a small boy. In some versions of the trick, Foo would produce a smaller bowl containing a fish. However, in each case the the giant bowl would be filled to the brim all making the illusion seem impossible. Again for anyone curious, the bowl was simply hidden below Foo’s flowing oriental robes and he used his finely honed sleight of hand skills to make it look like he was actually pulling from the folds of the cloth.

Robinson, who as you’ve probably guessed by now was quite adept at copying the tricks of other magicians was able to figure out how to perform the trick after observing Foo do it several times, and thus tried to take the Chinese illusionist up on his offer. For reasons that aren’t entirely clear though, Foo refused to meet with Robinson or honor the terms of the bet he’d made- something that understandably annoyed Robinson greatly.

In 1900, Robinson spied his chance for revenge in the form of an open call from a theatre in France that was looking for an act similar to Foo’s, only cheaper. Already familiar with Foo’s routine and evidently not concerned with the ethics of outright stealing the tricks and stage persona of other magicians, Robinson took the gig and travelled to Europe. Once there, he bought some old Chinese robes and did his best to alter his appearance to be more stereotypically Chinese. To really sell people on his ethnicity, Robinson also pretty much stopped talking to anyone publicly outside of his assistant, Suee Seen (who he billed as his wife, though in truth he’d left his real wife at home after they’d had a kid and she couldn’t travel with him anymore. However, owing to being Catholic he decided not to officially get divorced and just shacked up with Suee Seen for the rest of his life). As will probably not come as a surprise, Suee Seen was also not Chinese, rather an American woman called Olive Path who likewise attempted to modify her appearance as best she could to appear Chinese.

In any event, while performing in France, Robinson honed his skills to the point that he was eventually invited to headline shows in London. It was here that the magician decided to throw all pretence out of the window and began billing himself as Chung Ling Soo.

Under this new guise, Robinson achieved extreme success in London, becoming by all accounts one of the highest paid magicians in the world during the height of his fame. During this time, Robinson committed, somewhat admirably, to the role of Chung Ling Soo, never once breaking character in public as far as any primary accounts of him reveal.

This said, while it’s often claimed that nobody knew one of the most famous magicians in the world was really a white guy from America called William Robinson pretending to be Chinese, if you do some digging, it would appear pretty much everyone in the magical community knew his secret, but being a rather tight-nit group about secrets, nobody seems to have been willing to blow the whistle. That said, there is a 1902 article in Magic magazine that openly acknowledges that the two men were one in the same.

In any event, for four years Robinson performed throughout Europe as Chung Ling Soo without incident ,until 1904 when Ching Ling Foo’s troupe of magicians and Chinese acrobats arrived in London to play their rather popular show. This almost immediately caused a stir amongst Londoners as there was understandably confusion about which man was which given the similarity of their names and the fact that their acts were basically identical. This all was made worse by the fact that the theatres Chung Ling Soo and Ching Ling Foo were set to perform at were only about 100 feet apart.

Incidentally as a brief aside, at around the same time Chung Ling Soo and Ching Ling Foo were performing at neighbouring theatres in London there were at least two other Chinese magicians performing similar acts in the city. We only mention this because these two magicians billed themselves as Pee-Pa-Poo and Goldin Poo respectively.

Going back to Foo and Soo, naturally when Foo found out about Soo and his copycat act, he was rightfully incensed at Robinson’s gall and, sensing the opportunity for a juicy story, The Weekly Dispatch newspaper encouraged the magician to challenge Robinson to a magical duel.

Foo agreed and openly challenged his rival to replicate 10 of his tricks at the newspaper’s office- a challenge Robinson happily agreed to. Or so it would seem because it’s noted that Foo was so enraged by Robinson’s appropriation of Chinese magic that he added a second stipulation to his challenge- that Robinson “prove before members of the Chinese Legation that he is a Chinaman”. Something Robinson obviously could not do. Robinson (and the press) decided to heroically ignore this part of the challenge and mention of it was conveniently left out of press coverage of their feud. This so annoyed Foo that he didn’t turn up to the challenge in protest. This was something Robinson capitalised on by publicly declaring himself the winner, which was then gleefully reported on by the media who joked that Foo had turned up but had been made to disappear by Soo.

Foo’s reputation was so badly damaged by this amongst Londoners that many assumed that he was ripping off Soo and his previously wildly popular show elsewhere flopped completely in London and was canceled in under a month.

Soo’s copycat act, on contrast, was a hit and endured for months in London. His legitimacy now cemented in the eyes of the public and media, Robinson then spent the next 14 years performing as Chung Ling Soo, becoming immensely wealthy in the process. Ching Ling Foo, on the other hand, largely disappeared from public record after his feud with Robinson. Thus, funny enough, as the former news accounts alleged, Soo really did make Foo disappear.

Of course, as mentioned in the beginning, Robinson did eventually get a comeuppance of sorts when he died trying to perform the co-called “Condemned to Death by the Boxers” magic trick, with the name referencing the Chinese uprising known as the Boxer Rebellion.

After Soo’s death, how he’d done the trick in the past was officially revealed to the wider public, as was the fact that he was actually an American. As to the trick, he would have random members of the audience mark bullets. Muzzle-loaded guns would then be loaded with said bullets and fired at the magician by assistants at point blank range. After, he would show that he’d managed to catch the bullets, sometimes dramatically in his hands or other times even in his teeth. He would also, of course, display the markings for all to see.

In truth, he would simply use slight of hand to palm the marked bullets and different ones would be loaded. As to the guns, they were specially designed so that the main loaded gun powder charge would not fire, but rather a chamber below would fire a blank charge. This ensured that the bullet that was loaded would not ever exit the gun, but it would all appear as if the gun had fired normally.

As to what went wrong, after the performances the bullets and main charge would need extracted and, rather than do something simple like firing the gun normally, Soo would simply dismantle part of the gun and remove them manually. The issue was that it appears some residual gunpowder built up and on the fateful night in question flashed after the blank charge went off. This, in turn, set off the main charge and fired the bullet.

Robinson died a short while later- his last known words on stage and the subsequent news accounts pulling the curtain on arguably his greatest illusion of all- the fact that he wasn’t Chinese.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- How Did Harry Houdini Die?

- The Fascinating Origin of the Word “Abracadabra”

- From a Handmade Present for the Creator’s Daughter to a Multi-Billion Dollar Industry- The Story of the Troll Doll

- Wyatt Earp – The Great American… Villain?

- The Man Who Sold the Eiffel Tower

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Some of this is briefly touched on in the film The Prestige.

‘Tight-Knit’