When Did People Start Turning Things Up to 11?

In the hilarious rockumentary This is Spinal Tap released in 1984, Spinal Tap guitarist Nigel Tufnel proudly boasts of his Marshal amp, “This is a top to what we use on stage, but it’s very, very special because, if you can see, the numbers all go to 11. Look, right across the board: 11, 11, 11.”

In the hilarious rockumentary This is Spinal Tap released in 1984, Spinal Tap guitarist Nigel Tufnel proudly boasts of his Marshal amp, “This is a top to what we use on stage, but it’s very, very special because, if you can see, the numbers all go to 11. Look, right across the board: 11, 11, 11.”

Why this is so special is, of course, because, unlike mere mortal amps that only go to 10, as Tufnel states, “It’s one louder, isn’t it?”

Since then, the idea of turning things up to 11 has bled into pop culture. But, as it turns out, people were doings this long before Spinal Tap came onto the scene, both in directly turning something up to “11” and the more cliched way to say the same thing- giving 110%.

With regards to the latter, who exactly first got the bright idea to make 110% the gold standard for maximum effort isn’t clear, but around the early 20th century, usage of “110%” in this way went from seemingly a non-existent utterance in the 19th century to ubiquitous within the span of decades.

For example, consider this excerpt from the November 28, 1919 edition of The Palm Beach Post:

It was Artemus Ward who once made the assertion that he was compounding a medicine to cure certain ailments and called attention to the fact that “his formula contained 110 percent, while all other medicines in the world held but 100 percent”

Unfortunately, where the 19th century humorist Artemus Ward, aka Charles Browne, is to have said this isn’t clear, as none of his written works seem to have had this phrase.

Whatever the case, around this time, we have countless other references to this same type of thing, generally associated with either patriotism or sports. For example, consider this excerpt from the June 16, 1920 edition of the Jackson Daily News out of Mississippi,

Let our American friends be “100 percent Americans” all the time. This does not prevent me being “110 percent Scotch!” And I hope it will never prevent any of us from realizing that a real union of hearts, aims and aspirations between the two leading nations of the world can only lead to 100 percent happiness and prosperity for both.

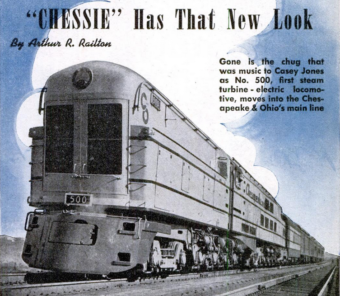

This all brings us to the first instance we could find of anyone ever explicitly wishing to turn something up to “11” instead of “110%” for maximal performance. This appears to come from a March of 1948 edition of Popular Mechanics where they interview a locomotive engineer working for the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway.

The subject of the article was the newly built steam/electric C&O No. 500 locomotive made by Baldwin Locomotive Works. Among other gems from that piece include extolling the virtue of coal/steam power instead of diesel as, to quote the designers “oil reserves may suffice for only 25-30 years at present consumption, while our coal reserves are good for 2000 years.”

As for turning it up to 11, during their conversation, the engineer explained to the interviewer that while in theory the train should be able to go in excess of 100 mph, nobody actually knew what the locomotive’s top speed was because of local speed limits on the railroads.

During a trial run with the interviewer, the article then notes,

By now the 500 is in open country and you look at the speedometer. The needle is hovering around 75 mph. That’s the speed limit here and the engineer takes his hand off the throttle. It’s on the seventh notch. The engineer grins. “Sure like to be able to pull it back to eleven!” he says.

You see, it turns out the C&O No. 500 had a throttle that went up to 11. As to why, this isn’t explained anywhere, though perhaps because the designers chose to use a 1, instead of a 0, base system, as the 1 setting was idle on this train, with 10 speeds beyond that.

Next up we move to music and Les Paul. In the early 1970s, Les Paul had a hand in creating what would later be dubbed “the ultimate Gibson Les Paul Guitar”- the Gibson Les Paul Recording Model.

Paul’s intention was for the instrument to offer guitarists an unprecedented amount of control over the sound they produced thanks to the equipment built into the guitar itself. He particularly targeted features commonly used by studio guitar players.

Towards this end, Paul made sure that the guitar featured a baffling array of options for the discerning guitarist via various knobs, dials and switches. The dial most pertinent to today’s topic is the so-called “decade switch” which, if interviews we read about it are to be believed, modified the treble harmonic sound from “smooth and silky” to “biting”. For those who really wanted extra bite, you could turn it up to 11.

It’s not clear why Les Paul did this instead of the more tradition 0 to 10, and we couldn’t find any interview anywhere of him explaining it, though we found several in which Paul extolled the virtues of this guitar, which apparently was his favorite to play all the way up to his death in 2009.

Clearly ahead of its time with its ability to turn something up to 11, according to Gibson, the Les Paul Recording Model was not well received, and suffered from limited sales before being discontinued about eight years after its creation, which just so happened to be around the time when This is Spinal Tap was first being sketched out.

Given its connection to music and the timing, you might be wondering if this particular guitar model inspired the gag in the film. Frustratingly, there doesn’t seem to be any quote or interview out there in which anyone asks how exactly the actors and/or writers came up with the “goes to 11” skit.

Given the dialogue for nearly the entire movie was improvised by the actors based on a rough outline of scenes, normally you might think they came up with it on the spot. However, in this case, Marshall didn’t make an amp with a plate with numbers going up to 11. Thus, this was definitely pre-planned.

And, in fact, if you look into it as we did, Christopher Guest (who played Spinal Tap lead shredder Nigel Tufnel in the film and did the commentary in character) stated in said commentary that they had Marshall produce a custom plate to attach to the front of the amplifier.

As for the original “script” (in the loosest sense of the word as it really just outlined the scenes), this was written by Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, Harry Shearer, and Rob Reiner; it simply said of the scene: “It’s like watching a kid show off his toys. He points out that he has his amps customized with special dials. Unlike most amps, whose highest volume level is indicated by a “10” on the dials, Nigel’s dials go up to 11.”

However they came up with the idea, Marshall reportedly had no intention to mass-produce the plates and in no way anticipated the popularity of the meme, which saw them being caught out when famous and not so famous guitarists across the world began requesting amplifiers that similarly “went up to 11” just like in the film.

According to legend, whether true or not we couldn’t verify, one of the first big name artists to request such an amplifier was Eddie Van Halen who upon seeing the film, immediately called Marshall to request such an amp- a request the company apparently were happy to comply with because, well, Eddie Van Halen.

For the more every day guitarist who couldn’t get a custom-made amplifier from the factory, Marshall did begin making plates similar to the one used in the film so that amp owners themselves could make it look like their amps went to 11.

The company later began releasing amplifiers with volume knobs that went to 20, and actually got Guest to reprise his role as Nigel Tufnel to advertise one of the earliest such amps- the Marshall JCM 900. On one ad for the JCM 900 you can see Guest, in character as Tufnel, proudly boasting “now it goes to ‘20’” which he assures people is “9 louder, innit!”

Although Tufnel was evidently happy enough with Marshall’s new amp that went to 20 to advertise it, in later in-character appearances as Tufnel, Guest has claimed to own an even better custom amp. To quote him, “When Joe [Satriani] first played with us… about a year ago… in Los Angeles, he was very frightened, you know, mostly from the volume because he plays it a little bit lower than we do. My new amplifiers now go to infinity and I think that idea was very scary to him because most amplifiers go to ten, but I made the jump to infinity…”

According to Tufnel, this amp was custom made by Marshall just for him and since it’s not technically possible to create an amp that is “one louder” than infinity, he still gets to claim to play the loudest amp in the entire world despite many people at that point having purchased amps that were capable of going to not just 11, but 20.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Tom Waits vs. the World (Of Advertising)

- That Time a Band Made Over $20,000 on a Totally Silent Album on Spotify

- Why British Singers Lose Their Accents When Singing

- NASA and Their Real Life Space DJ’s

Bonus Facts:

- Speaking of fake Hollywood bands that ultimately turned into the real thing in some respects, The Monkees were huge fans of Jimi Hendrix before he really made it big, so invited him to open for them on tour. This, however, didn’t go over very well with The Monkees‘ fan base. His performances at these shows were often cut short with the audience booing or chanting for The Monkees until he got off the stage. As a result of this, he asked to leave the tour. In order to help him get more media attention from the break, The Monkees claimed Hendrix was forced to leave because his performances were “lewd and indecent.”

- Jimi Hendrix joined the army, not because he wanted to be a soldier, but because he didn’t want to go to jail. He was arrested for riding around in stolen cars (twice) and the second time they told him he could spend two years in prison or join the army- he chose to enlist in the army and was assigned to the 101st Airborne Division. This didn’t last long though as he was constantly getting in trouble for sleeping while on duty and disregarding rules and regulations. His commanding officers finally requested that he be discharged, which he was.

Before this discharge came through, Hendrix supposedly pretended to be gay to try to get out of the military (according to Charles Cross’ biography on Hendrix), but was unsuccessful in that attempt. On that note, in the song “Purple Haze”, Hendrix has a line “Excuse me, while I kiss the sky.” This gave rise to some people misinterpreting the lyrics “Excuse me while I kiss this guy.” As a result of this, Hendrix reportedly would occasionally sing the latter line in his actual performances because he thought it was funny. - Speaking of phenomenal guitar players and connections to actors, one of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s first bands when he was 14 years old was Cast of Thousands. This band’s lead singer was none other than future actor Stephen Tobolowsky (BING!!!), who has since appeared in Heroes, Glee, CSI, Miss Congeniality 2, Sneakers, Kingpin, and Groundhog Day, among literally hundreds of others.

- Incidentally, Tobolowsky passed up the role of Al on Home Improvement. At the time, his wife was pregnant and he didn’t have much money. They offered him $16,000 per episode to play that role, which he was excited to take until they told him the pilot might not be filmed for six months, but their contract had a stipulation that he’d have to be exclusive to the show while working for them, which meant he might only get paid $16,000 during a six month span for the one episode and maybe nothing after if the show wasn’t picked up. Thus, with his child on the way, he turned down the role and took a few minor movie offers. It all worked out though, with some of the roles he took during the Home Improvement run launching his career as a staple “guest star” type actor, including his role in Groundhog Day.

- Ever wonder how Eric Clapton got the nickname “Slowhand”, well, wonder no more- When most guitar players break a string on stage, a roady will typically bring them another guitar and fix the string on the old one off-stage. Clapton, on the other hand, had a practice of standing on stage and replacing and tuning the string in front of the audience. While he was doing this during one particular performance, the audience gave him a slow clap or a “slow hand” until he had fixed it and was ready to play again. This “slow hand” clap eventually became a thing in his performances. According to Clapton, the guy that managed the Yardbirds, Giorgio Gomelsky, gave him the nickname “Slowhand” from this- “He coined it as a good pun. He kept saying I was a fast player, so he put together the slow handclap phrase into Slowhand as a play on words.”

- During his college years, Leo Fender, founder of Fender Guitars, studied to be an accountant while pursuing electronics as a hobby, though never taking any electronics courses. For quite some time after graduating, Fender worked as an accountant. However, after losing his job due to the Great Depression, he opened the “Fender Radio and Record Shop” in Fullerton, CA where he was able to combine his love of music and tinkering with electronics. Initially, part of the service he offered at his shop was amplifier repair. This led to Fender designing and building his own amplifiers to get around many of the design flaws he found in existing amplifiers. He later went beyond amplifier design and repair and moved into instrument design itself. On that note, despite designing the first commercially successful solid-body electric guitar, the Telecaster; designing the most influential of all electric guitars, the Stratocaster; and inventing the solid-body electric bass guitar, the Precision bass, Fender was not a musician and he couldn’t himself play a lick of guitar! As such, he had to bring in musicians to properly test out the prototypes of his guitars.

- Spinal Tap – Tufnel Interview

- Les Paul Recording Guitar

- Amps That Go to 11

- Les Paul Recording

- Chesapeake and Ohio

- Popular Mechanics Mar 1948

- The A-Z of Spinal Tap

- History of the Expression Give 110%

- Popular Mechanics Magazine: Written So You Can Understand it, Volume 89, Issue 1

- Les Paul’s Favorite Les Paul – The Recording Model

- Nigel Tufnel about Joe Satriani – Video

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

This got me intrigued as to how a steam/electric locomotive works.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steam_turbine_locomotive#Electric_transmission

A steam turbine drives a generator which powers electric motors which drive the wheels. The C&O 500 of the story was a lemon. “These locomotives were intended for a route from Washington, D.C. to Cincinnati, Ohio but could never travel the whole route without some sort of failure.” (Wikipedia.) The wikipedia article also has a photo so much like the illustration at the top of this page that surely the illustration was copied off this photo.

The 500-503 locomotives certainly could travel the entire route without a failure. They were too complex and some of the materials available in the 40’s were not able to withstand the forces which materials now can. They were well thought out but not real well designed.

A couple of years ago, I bought 2 new Klipsch 15″ subwoofers (R-115-SW) to go under my big Klipsch Chorus speakers… The “gain” knob on the back goes to 11. 🙂

-At “7” they are already backing out the drywall nails in the room, so I can’t imagine what “11” sounds like!