The Curious Case of Alexis St. Martin

Being shot directly in the stomach isn’t generally conducive to living- a fact that makes the story of Alexis St. Martin all the more impressive because he not only walked off being shot in said organ at the age of 20 on June 6, 1822 at a range of less than a meter, but went right ahead and lived for another half century despite the wound going full Weathertop on him and never completely healing, giving scientists an almost literal window into how the body digests food.

Being shot directly in the stomach isn’t generally conducive to living- a fact that makes the story of Alexis St. Martin all the more impressive because he not only walked off being shot in said organ at the age of 20 on June 6, 1822 at a range of less than a meter, but went right ahead and lived for another half century despite the wound going full Weathertop on him and never completely healing, giving scientists an almost literal window into how the body digests food.

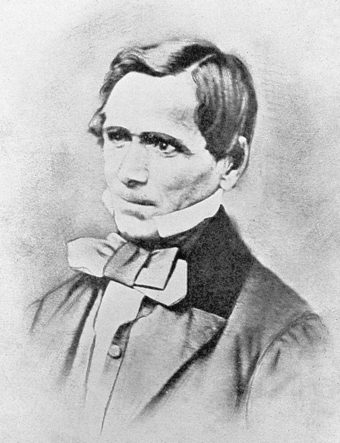

So how did this all come about? Martin, an illiterate French Canadian indentured servant working as a fur trapper for the American Fur Company, was shot in the gut by a fellow trapper at the Mackinac Island trading post. Exactly what happened isn’t clear, but it’s largely agreed that the whole thing was just an unfortunate accident caused by the fellow trapper accidentally discharging his weapon.

Within a half hour, the resident army physician stationed at Mackinac Island, Dr William Beaumont, was looking over St Martin. What he saw wasn’t pretty:

The [duck shot] entered posteriorily, and in an oblique direction, forward and inward, literally blowing off interguments and muscles of the size of a man’s hand, fracturing and carrying away the anterior half of the sixth rib, fracturing the fifth, lacerating the lower portion of the left lobe of the lungs, the diaphragm, and perforating the stomach.

The whole mass of materials forced from the musket, together with fragments of clothing and pieces of fractured ribs, were driven into the muscle and cavity of the chest….

He goes on,

found a portion of the lung as large as a turkey’s egg, protruding through the external wound, lacerated and burnt; and immediately below this, another protrusion, which, on further examination, proved to be a portion of the stomach, lacerated through all its coats, and pouring out the food he had taken for his breakfast, through an orifice large enough to admit the forefinger…

Naturally, Beaumont saw little hope that St. Martin would make it through the night, but operated as best he could anyway and, against all expectations, St Martin survived.

A problem arose, however, when attempts were made for St Martin to eat and drink. You see, thanks to the gaping hole in his stomach, anything swallowed ultimately just ended up gushing right out of the hole shortly thereafter.

Undeterred, the enterprising Beaumont simply spent weeks feeding St. Martin via “nutritious enemas”…

This worked.

After a few weeks, Beaumont reported that rectal feedings became unnecessary, despite the hole in the stomach remaining. They got around the problem via applying “compresses and adhesive straps” to St Martin “so as to retain his food.”

Remarkably, Beaumont also notes, “No sickness nor unusual irritation of the stomach, not even the slightest nausea, was manifest during the whole time; and after the fourth week, the appetite became good, digestion regular, the… evacuations natural, and all the functions of the system perfect and natural.”

After five weeks, St Martin was healing nicely most everywhere except the troublesome hole in his stomach. Rather than healing naturally, it had become more or less attached to the hole in the skin, forming something of sphincter with a slight prolapse of the stomach pushing through it. Because of this, continued application of compresses was needed for St Martin to retain food and drink.

Eight months later, Beaumont was still attempting various, sometimes very painful, means to get the wound to close itself with no success. He then suggested cutting the stomach away from the skin and attempting to suture everything back up, but at this point St Martin had had enough. Otherwise mostly healthy and fully functional, other than, you know, the literal hole in his stomach and abdomen, he refused the surgery.

In the interim of all this, St Martin was released from his indentured servitude contract and booted out of the hospital as he had no money to pay. Beaumont, however, saw a golden opportunity in St Martin to study the human digestive tract up close and personal… And we mean personal. For example, at one point he literally stuck his tongue in the hole, noting, “On applying the tongue to the mucous coat of the stomach, in its empty, unirritated state, no acid taste can be perceived…”

Up to this point, very little was definitively known about how the human digestive tract worked exactly. Doctors in the past had done things like experimented on animals, but this inevitably led to the animal’s death so observing a working digestive tract wasn’t exactly feasible. Likewise dissecting human bodies was a thing, but, again, this isn’t terribly helpful in watching the process of digestion on a living organism.

To attempt a way around this, some doctors had tried things like tying strings to mesh bags filled with food items and then swallowing them- waiting some period, and then pulling the item back out through the mouth. But nobody had ever had a guinea pig like St Martin to play with.

As such, Beaumont offered to sign St Martin as an indentured servant to himself, primarily working as a laborer for Beaumont but also with the agreement that Beaumont would be able to experiment on St Martin in pretty much any way he wanted. And, given the terms of the agreement and St Martin’s extreme lower class status, this really was very much “any way he wanted” with seemingly little regard for St Martin’s feelings about things once the contract was signed.

While the terms of this initial contract are not known today, a later contract he signed with Beaumont has survived and in that one, in return for St Martin being a servant to Beaumont and his guinea pig, Beaumont would cover St Martin’s room and board and would also pay him $150 per year (about $2,800 today).

After a few years of this, St Martin broke his contract and left without permission, heading up to Canada where he started a family. Perturbed, but nonetheless still wanting to study St Martin, Beaumont spent a considerably sum of money tracking St Martin down and then convincing the fur company St Martin was then working for to allow him to return. He then offered St Martin things like a huge increase in pay, land granted by the government, and money to relocate his family (or better yet even more money to abandon his wife and kids). However, privately, he darkly wrote, “When I get him alone again into my keeping, I will take good care to control him as I please.” He also variously referred to St Martin’s children in a letter as “live stock” and in a letter to the U.S. surgeon general lamented St Martin’s “villainous obstinacy and ugliness”. Beyond all this, when writing about St Martin, he generally referred to him as “boy” rather than calling him by his name.

But before all that, with lapses here and there due to the aforementioned instances of St Martin fleeing the doctor’s not so tender care, Beaumont basically spent his time dropping or shoving random things into St Martin’s stomach to see what happened- and we do mean “see” because he often used instruments to keep the hole open and as wide as possible so he could observe food and drink entering and then what happened after, noting in this way he could see “to the depth of five or six inches…”

Beyond sticking his tongue in the wound, he also occasionally would extract things, including stomach tissue and food items. On the latter, after extraction, he even sometimes taste tested them, for instance at one point writing that partially digested chicken tasted “bland and sweet”…

Beaumont also spent considerable time extracting stomach acid to then experiment with separately, including sending samples around to other doctors looking to do experiments. As to this uncomfortable procedure, he wrote,

On introducing the tube, the fluid soon begins to flow, first by drops, then in an interrupted, and sometimes in a short continuous stream. Moving the tube about, up and down, or backwards and forwards, increases the discharge. The quantity of fluid ordinarily obtained is from four drachms to one and a half or two ounces…

Its extraction is generally attended by that peculiar sensation at the pit of the stomach, termed sinking, with some degree of faintness, which renders it necessary to stop the operation. The usual time of extracting the juice is early in the morning, before he has eaten, when the stomach is empty and clean.

Fascinatingly, despite the wound never healing, Beaumont did report a rather odd occurrence that happened about a year and a half after the initial injury:

At this time, a small fold or doubling of the coats of the stomach appeared forming at the superior margin of the orifice, slightly protruding, and increasing till it filled the aperture, so as to supersede the necessity for the compress and bandage for retaining the contents of the stomach. This valvular formation adapted itself to the accidental orifice, so as completely to prevent the efflux of the gastric contents when the stomach was full…

Thus, while the hole in St Martin’s stomach and abdomen still persisted, an effective sphincter of sorts made up of stomach tissue formed to allow St. Martin to no longer necessarily need a wrap to keep the contents of his stomach from falling out.

In any event, the various discoveries Beaumont made over the course of years of experimenting on St Martin ultimately saw him named “The Father of Gastric Physiology” and helped lay the groundwork of our modern understanding of the human digestive process.

Amazingly, St Martin lived to the ripe old age of 78, siring 6 children and otherwise living a pretty normal, if mostly impoverished, life.

As for after, while inquiries were made by doctors to acquire St Martin’s body when he died, his family had anticipated this, reportedly leaving his body out in the sun for a time until it was quite decomposed and then burying him in a secret location to avoid any chance anyone would be able to dig him up and perform an autopsy. As to specific inquiries, one doctor boldly sent a medical bag for St Martin’s family to mail the stomach back in. Instead, they simply replied with a telegram stating, “Don’t come for autopsy, will be killed.”

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Curious Case of Ronald Opus

- The Curious Case of Coffin Births

- Medical Oddities: Brewing Beer In Your Digestive Tract

- The Curious Case of the Campden Wonder

- The Curious Case of Alien Hand Syndrome

| Share the Knowledge! |

|