Forgotten Heroes: The Accidental Farmer

Bob Fletcher was an agricultural inspector working in California’s Central Valley in the early 1940s. He might have stayed one, too, had the outbreak of World War II not changed everything.

Bob Fletcher was an agricultural inspector working in California’s Central Valley in the early 1940s. He might have stayed one, too, had the outbreak of World War II not changed everything.

INFAMY

Shortly before 8:00 a.m. on the morning of December 7, 1941, Japanese military forces attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, on the Hawaiian Island of Oahu. More than 2,400 soldiers were killed in the attack, 18 warships were sunk or damaged, and 188 aircraft were destroyed. The surprise attack was just the opening shot in a military campaign that stretched across Southeast Asia and the Pacific. In the days and weeks that followed, the U.S. territories of Guam, Wake Island, and the Philippines fell to the Japanese. So did the British possessions of Hong Kong, Malaya (part of modern-day Malaysia), Burma, and Singapore, as well as the Netherlands Indies (part of modern-day Indonesia) and the nation of Thailand.

As one territory after another was captured by Japan, for a time it seemed like their advance might never be stopped. Would Australia be next? The West Coast of the United States? With much of the Pacific Fleet destroyed or knocked out of commission at Pearl Harbor, an invasion of the western United States was a very real—and terrifying—possibility.

GUILT BY ASSOCIATION

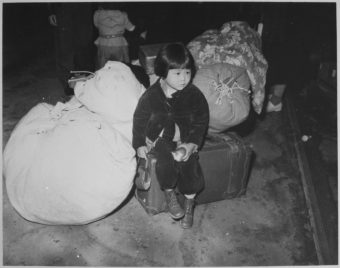

One group that fell victim to the hysteria that followed was the Japanese American community of families who lived on the West Coast. Many were descended from immigrants who settled in the United States as far back as the 1860s; ties to their ancestral homeland were tenuous at best. No matter: In February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the military to designate the entire state of California, as well as parts of Arizona, Oregon, and Washington, as “military areas” from which “any or all persons may be excluded.” As a consequence of the order, more than 110,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese American citizens were forced from their homes and transported to internment camps far from home. There they were kept under armed guard for the rest of the war. It was the largest forced relocation in American history.

One group that fell victim to the hysteria that followed was the Japanese American community of families who lived on the West Coast. Many were descended from immigrants who settled in the United States as far back as the 1860s; ties to their ancestral homeland were tenuous at best. No matter: In February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the military to designate the entire state of California, as well as parts of Arizona, Oregon, and Washington, as “military areas” from which “any or all persons may be excluded.” As a consequence of the order, more than 110,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese American citizens were forced from their homes and transported to internment camps far from home. There they were kept under armed guard for the rest of the war. It was the largest forced relocation in American history.

“OUSTER OF ALL JAPS IN CALIFORNIA NEAR!” screamed one San Francisco Examiner headline in February 1942. The forced internments were popular with the American public, but one man who was appalled by them was Bob Fletcher, a 33-year-old state agricultural inspector who had gotten to know many Japanese American farmers in the Central Valley, the agricultural heart of California. Some of these families had been on the land for three generations. With no way to pay their bills while they were locked away in the camps for years on end, they risked losing everything they had.

One Japanese American who Fletcher knew fairly well was a farmer named Al Tsukamoto. Around the time that notices appeared on telephone poles in the town of Florin, near Sacramento, ordering Japanese Americans to report to the train station in nearby Elk Grove to be taken away to internment camps, Tsukamoto came to Fletcher with a request. Two of his neighbors, the Okamotos and the Nittas, were looking for someone to manage their farms while they were interned. If Fletcher was willing to run their farms, keep the books, and pay the bills while the families were away, whatever money was left over was his to keep as payment for his labor.

BACK TO THE LAND

Fletcher had been raised on a walnut farm, and during the Great Depression he managed a peach orchard. But he had no experience growing Flame Tokay table grapes, which was the two farms’ main crop. Nevertheless, he was bothered by the fact that decent people like the Okamotos and the Nittas could lose their farms, so he agreed to do it. Then when Tsukamoto decided he needed someone to take over his farm as well, Fletcher agreed to look after all three farms. He quit his job as an agricultural inspector and moved into an unoccupied bunkhouse on Tsukamoto’s farm. Tsukamoto had invited Fletcher to move into his own home, but Fletcher was uncomfortable with the idea of living there when Tsukamoto could not, so he stayed in the bunkhouse.

There must have been times when Fletcher wondered what he’d gotten himself into, because he was soon putting in 18-hour days tending Flame Tokay grapes, strawberries, blackberries, boysenberries, and olive trees—more than 100 acres of produce in all. In addition to the hard work, he also had to put up with the disapproval of his neighbors, many of whom supported the forced internments and considered Fletcher a “Jap lover” who was aiding and abetting the enemy. Once he was nearly shot when someone fired a gun into Tsukamoto’s barn while he was inside. But he toughed it out, and in defiance of his neighbors he kept the farms going until the war ended, the internment camps closed, and the families were able to return home.

Those families that still had homes, that is: of the 2,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans who had lived in and around Florin before the war, only about 20 percent, or some 400 people, returned to live there after the war. Where would the rest have stayed? Their homes and farms were gone—foreclosed upon or otherwise stolen from them when they were imprisoned in the camps.

WELCOME MAT

When the Nittas, the Okamotos, and the Tsukamotos began making their way back to Florin, they too must have wondered what awaited them. What they found was what they’d hoped they’d find: their homes and farms still intact, and Bob Fletcher tending to their crops. He was newly married to his wife Teresa, who was helping him with the farm chores. (Even after marrying, the Fletchers did not move into the Tsukamotos’ house, which would have been more comfortable for the newlyweds than the spartan bunkhouse. But doing so felt wrong, so they didn’t—“It’s their house,” Teresa Fletcher explained.)

The families did find one surprise when they got home: money in the bank. The agreement the Nittas, the Okamotos, and the Tsukamotos made with Fletcher was that if their farms managed to eke out a profit, he could keep the money in payment for his labor. But Fletcher decided to split it with them, and their half was in the bank, earning interest—a sizable nest egg that they could use to restart their lives.

A LASTING FRIENDSHIP

Fletcher must have enjoyed farmwork because after the war he bought a ranch of his own, and raised hay and cattle. He also volunteered for the Florin Fire Department and served 12 years as fire chief. He retired in 1974 and lived to the age of 101. On his 100th birthday in July 2011, his family threw a huge birthday bash. Teresa, his wife of 66 years, was by his side, as were his son, three granddaughters, and five great-grandchildren. So were quite a handful of Nittas, Okamotos, and Tsukamotos. And though Fletcher never sought recognition for the helping hand he gave his neighbors during the war, they were eager to share his story. “We had forty acres of Flame Tokay grapes and we would have lost it if Bob didn’t take care of it,” Doris Taketa told the Sacramento Bee. She was 12 when her family was sent with to an internment camp in Arkansas. “My mother called him God,” she said, “because only God would do something like that.”

When asked by reporters at the birthday party why he did what he did, Fletcher’s answer was simple. “They were the same as everybody else,” he said. “It was obvious they had nothing to do with Pearl Harbor.”

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s OLD FAITHFUL 30th Anniversary Bathroom Reader. Uncle John and the Bathroom Readers’ Institute! Every year for the past three decades, Uncle John and his team of tireless researchers have delivered an epic tome packed with thousands of fascinating factoids. And now this extra-special 30th anniversary edition has everything you’ve come to expect from the BRI, and more! It’s stuffed with 512 pages of all-new articles sure to please everyone, from our longtime readers to newbies alike. You’ll get the scoop on the latest “scientific” studies, weird world news, surprising history, and obscure facts.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s OLD FAITHFUL 30th Anniversary Bathroom Reader. Uncle John and the Bathroom Readers’ Institute! Every year for the past three decades, Uncle John and his team of tireless researchers have delivered an epic tome packed with thousands of fascinating factoids. And now this extra-special 30th anniversary edition has everything you’ve come to expect from the BRI, and more! It’s stuffed with 512 pages of all-new articles sure to please everyone, from our longtime readers to newbies alike. You’ll get the scoop on the latest “scientific” studies, weird world news, surprising history, and obscure facts.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Boy, if this story doesn’t cry out for a movie treatment, I don’t know what does.

true. Hasn’t it been made?

I grew up there, off Florin Road, south sac county, 5 minutes from the town of Florin. I never heard of him or this story. None of our Japanese neighbors ever talked about it. It was never brought up at school.

Our local grocery store was run by Asian families. I was about 12 yrs old before I realized that not all stores have 100 lbs sacks of rice for sale next to the magazine rack…

Great story. Thanks a lot.

FDR was a Democrat. Typical of racial profiling. Made it possible for the Nissei to be robbed of freedom, rights of ownership and future enterprise. Not unlike the Demoncrats who created “Jim Crow” laws, oppressed black ppl, forbade inter racial marriage, and fought Civil Rights legislation. I am a Democrat and I am ashamed of this legacy.