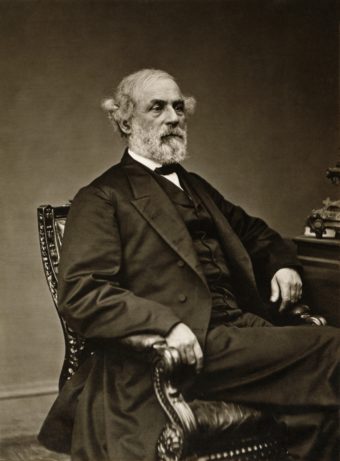

The Difficult Decisions of Robert E. Lee

If you look back on your life, you can probably point to a time or two where you were faced with a really tough decision. Had you chosen differently, your world would look very different right now. So it was for Confederate general Robert E. Lee (1807–70)—one of the most divisive figures in American history. To his fans, Lee was the hero of the Civil War—which explains why there are so many roads and schools named after him in the South. But to his critics, Lee was a traitor who fought to keep slavery legal. It turns out that Lee was just as conflicted as his legacy. Let’s look at Lee’s life through the scope of some of those choices to look at the impact they did have…and are still having today.

If you look back on your life, you can probably point to a time or two where you were faced with a really tough decision. Had you chosen differently, your world would look very different right now. So it was for Confederate general Robert E. Lee (1807–70)—one of the most divisive figures in American history. To his fans, Lee was the hero of the Civil War—which explains why there are so many roads and schools named after him in the South. But to his critics, Lee was a traitor who fought to keep slavery legal. It turns out that Lee was just as conflicted as his legacy. Let’s look at Lee’s life through the scope of some of those choices to look at the impact they did have…and are still having today.

DECISION 1: MATHEMATICS OR MILITARY?

Robert Edward Lee was born in 1807 to one of Virginia’s most wealthy and respected families. When he was 18 years old, he applied to West Point Military Academy in New York, which was expected of a young man of his social status. But late in life he confided to a friend that attending a military college was among his greatest regrets. It may seem like an odd comment for a man who was venerated as a war hero, but as a boy it was mathematics, not soldiering, that interested him. Robert was an intelligent child and could have studied to become a teacher, architect, or an engineer. But there was another factor in play: the once-proud family name had been tarnished.

Two centuries earlier (a few years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock), Richard Lee I emigrated from England to begin a new life in what is now Virginia. That was Robert E. Lee’s great-grandfather. Lee’s grandfather was Colonel Henry Lee II, a prominent Virginia politician. And Lee’s father, Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee III, fought alongside George Washington in the Revolutionary War. In fact, at Washington’s funeral in 1799, it was Harry Lee who famously described the late general and president as “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” Harry Lee would go on to become Virginia’s governor and then a U.S. congressman.

But things turned sour for the family when Harry’s poor financial habits and risky business ventures led to bankruptcy and a one-year stint in debtor’s prison. A few years later, during the War of 1812, Harry was nearly beaten to death after defending a friend who opposed the war. He fled to the West Indies to “heal,” but it was more likely to escape his debts. He died before he could make it home.

HONOR THY FATHER

With his father gone, and his older brother away at Harvard, it was left to Robert to care for his invalid mother and help raise his younger siblings. His mother instilled in him a sense of honor, never letting him forget that he was born into a family that had produced a governor, a U.S. congressman, a U.S. senator, a U.S. attorney general, and four signers of the Declaration of Independence. Even so, the name “Lee” didn’t have the clout it once did.

So one reason for Lee’s application to West Point was to restore honor to his family. (Another reason: it was much cheaper than Harvard.) He nearly didn’t get in because of his father’s reputation, as by that point he had become known primarily as “the man who once wrote George Washington a bad check.” But Lee was accepted, and that’s where his rise began. An exemplary student, Lee earned zero demerits in his four years there, which is almost unheard of at the strict military academy. In 1829, after graduating second in his class, his high marks earned him the rank of second lieutenant in the prestigious Army Corps of Engineers. He then married Mary Custis, the great-granddaughter of Martha Washington. That alone went a long way to restoring the Lee name.

During the 1830s and early ’40s, when the United States was at peace, Lee had the opportunity to put his math skills to work by fortifying the nation’s borders. As a U.S. Army engineer, he helped map the line between Ohio and Michigan, and was part of the team that rerouted the Mississippi River back toward St. Louis.

MEANWHILE, IN TEXAS

A few years later, the United States went to war against Mexico over the annexation of Texas. Lee, now a captain, was dispatched there in 1847 to map routes over rough terrain that American soldiers could use to gain an advantage over the Mexicans. His tactical prowess led directly to winning several crucial victories…and eventually the war. And it put Lee on the map as a rising star in the U.S. Army. His commander, General Winfield Scott, called him “the very finest soldier I ever saw in the field.”

When Lee was giving a speech to the troops during the Mexican-American War, one of the soldiers in attendance was Ulysses S. Grant, who admired Lee. When the war ended, the two men went their separate ways, on either side of the Mason-Dixon Line (which ran between Virginia and Maryland, and divided the nation between North and South). Little did they know their lives and their legacies would be forever linked.

DECISION 2: CAPTURE BROWN, OR WAIT IT OUT?

In 1859, Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee and a squad of marines were sent to Harpers Ferry, Virginia, to prevent a slave revolt. A group of 21 abolitionists led by a 58-year-old white Northerner named John Brown had taken over a military arsenal. Their mission: free every slave and kill their captors if they had to (which they had already done on a few occasions). At Harpers Ferry, Brown and his men captured several townspeople, including George Washington’s great-grandnephew, and held them as hostages. When Lee arrived, his main objective was to capture Brown, but he was also there to ensure the safety of any townspeople, black or white, who refused to side with Brown. After a tense standoff, Lee sent one of his commanders to approach the arsenal with a white flag. Brown was told that if he surrendered, none of his men’s lives would be lost

“No,” replied Brown, “I prefer to die here.”

That brought Lee to his next big decision: Should he send his men in to capture by force and perhaps even kill Brown—whom he described as a “madman”—but doing so, possibly turn Brown into a martyr in the North, which would further divide the already divided nation? Or should Lee cut off Brown’s provisions and wait him out, in the hope that the revolt would fizzle? Lee chose to send in the troops. They captured Brown after a bloody firefight in which several people were killed—including two of Brown’s sons—but no hostages.

John Brown was convicted of murder, conspiracy to incite a slave uprising, and treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia. He was hanged for his crimes. Just as Lee had feared, Brown’s death became a rallying cry for the North, though he was vilified as a murderer and a terrorist in the South. When Abraham Lincoln was elected president a year later on an antislavery platform (without winning a single state below the Mason-Dixon Line), many in the South saw that as the last straw. Slavery had been outlawed in the northern states for several decades, and most Southerners could see no other choice than to fight the “northern aggression” or lose their way of life. War was looming.

DECISION 3: WHICH SIDE SHOULD I FIGHT FOR?

Next came the most difficult decision of Lee’s life. He was both a proud American and a proud Virginian. Today, it’s accepted that the federal government is responsible for setting the national agenda with regard to laws, taxation, education, and more. In the 19th century, Washington, D.C., had a lot less direct oversight over people’s lives. The states made their own laws—including laws relating to slavery. Like most Americans of his generation, Lee’s loyalty was to his state first, and his country second.

That didn’t mean he wasn’t alarmed when several Southern states—South Carolina, Alabama, Georgia, Texas, and Louisiana—seceded from the Union after Lincoln was elected. Lee feared that Virginia’s leaders would follow suit, and he thought it was a major overreaction to the problem, stating, “I do not believe in secession as a constitutional right, nor that there is sufficient cause for revolution.”

But after Virginia’s lawmakers voted by a narrow margin to secede in April 1861 and join the newly formed Confederate States of America, Lee suddenly found himself as a man without a country. He didn’t want to fight for either side. He sought the counsel of General Scott, director of the Confederacy’s War Department. Scott’s advice: “You cannot sit out the war.” The situation became even more complicated after President Lincoln, an admirer of Lee, offered him the chance to lead the Union army in the war. Lee had to think about it for a few days. He ultimately confided,

I look upon secession as anarchy… If I owned the four millions of slaves in the South I would sacrifice them all to the Union, but how can I draw my sword upon Virginia, my native state?

SACRIFICE

So when it came down to choosing between the North and the South, Lee chose neither. He chose Virginia. Turning down Lincoln’s offer, he resigned his commission with the U.S. Army after serving with distinction for 32 years. A few weeks later, Lee accepted Confederate president Jefferson Davis’s offer to serve in the Army of Northern Virginia, the first line of defense against invading Union soldiers. Within a year Lee would be in charge of the entire Confederate military.

History buffs can only speculate about what would have transpired had Lee accepted Lincoln’s offer, but it’s hard to imagine a worse fate than a war that killed more than 620,000 people. In his 2014 book, A Disease in the Public Mind, historian Thomas Fleming theorizes that the outcome would have been much better:

General Lee would have remained in command of the Union army, ready to extinguish any and all flickers of revolt. By expertly mingling his troops so that Southern and Northern regiments served in the same brigades, he would have forged a new sense of brotherhood in and around the word ‘Union.’ At the end of President Lincoln’s second term, it seems more than likely that the American people would have elected Robert E. Lee as his successor.

DECISION 4: FOLLOW ORDERS, OR FOLLOW MY HEART?

But that didn’t happen, and four years later, the Confederacy had all but lost the Civil War. And Lee knew it. After some early successes in driving off invading Union troops—which earned him a lot of respect on both sides—Lee lost both of his major incursions into the North at the battles of Antietam and Gettysburg, two of the bloodiest of the war.

Lee, now in his mid-50s, was suffering from heart problems that kept him sidelined for weeks at a time. After Gettysburg, he even tried to resign his commission, but President Davis talked him out of it. Yet despite the losses, the Confederate soldiers still looked up to him. Why? Unlike many commanders who traveled with servants and slept on soft beds, Lee chose to be with his troops, both on and off the battlefield. Lee biographer Peter S. Carmichael wrote that the soldiers had “extraordinary confidence in their leader, extraordinary high morale, a belief they couldn’t be conquered. But at the same time it was an army that was being worn down. Lee was pushing these men beyond the logistical capacity of that army.”

As the South ran low on supplies, and the desertion rate among Confederate soldiers increased, Lee proposed a radical plan: train the slaves to fight. That idea did not go down well. “The proposition to make soldiers of our slaves is the most pernicious idea that has been suggested since the war began,” complained Georgia governor Howell Cobb. “The day you make a soldier of them is the beginning of the end of the Revolution. And if slaves seem good soldiers, then our whole theory of slavery is wrong.”

President Davis agreed with Cobb, and Lee’s request was denied. Lee told Davis there was only one option left: surrender to the North so no more lives would be lost for a losing cause.

Davis wasn’t ready to give up, though. He ordered Lee to keep the war going by using guerrilla tactics—sending small squads into Northern strongholds to fight, hand-to-hand if necessary. Knowing that a guerrilla war could go on for years, Lee found himself in yet another difficult position: should he follow the orders of his commander-in-chief, or do what he thought was right?

On April 9, 1865, with his troops heavily outnumbered in the town of Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, Lee knew it was time. “I suppose there is nothing for me to do but go and see General Grant,” he said. “And I would rather die a thousand deaths.”

The two generals held an official ceremony in which Lee surrendered, and the Civil War was over.

DECISION 5: RETIRE IN PEACE, OR WORK FOR PEACE?

When Lee chose to align himself with Davis, not Lincoln, he was effectively renouncing his U.S. citizenship. So when the war ended, he was a man without a country. He couldn’t vote, much of his land had been seized in the war (including his home, the Custis-Lee Mansion, which is now Arlington National Cemetery), and he was nearly broke. According to South Carolina writer Mary Chestnut in Civil War Diaries, right after the war she overheard Lee telling a friend that he “only wanted a Virginia farm—no end of cream and fresh butter, and fried chicken.” But as much as he yearned for a quiet life, Lee’s sense of duty brought him to the White House to publicly advocate for Reconstruction. That made him, according to Civil War scholar Emory Thomas, “an icon of reconciliation between the North and South.”

BACK TO SCHOOL

For Lee’s final act, he saved a school. Washington College, located in Lexington, Virginia, had been left in tatters after the war. Five months after the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse in September 1865, Lee was offered the job as the school’s president. The use of his name, which was still hallowed in the South, would be a boon to any institution (and he reportedly turned down several other, more lucrative positions that would have capitalized on his name). Lee agreed to take the job—in part because of his respect for George Washington, for whom the school was named, but also because he believed that an educated populace would be less likely to wage war. “It is well that war is so terrible,” he once said, “we should grow too fond of it.”

Under Lee’s leadership, Washington College grew from a small Latin school to a university that offered students (just white males at the time) the opportunity to major in journalism, engineering, finance, and law. He fused those with the liberal arts, which was almost unheard of at the time. He even recruited Northerners to become part of the student body in yet another effort to heal a broken nation. “The students fairly worshipped him, and deeply dreaded his displeasure,” wrote one of the professors, “yet so kind, affable, and gentle was he toward them that all loved to approach him.”

The school, now known as Washington and Lee University, is still going strong today. Now fully integrated with women and African Americans (though it took until the 1970s for that process to become complete), the school has produced four U.S. Supreme Court justices; 27 U.S. senators; 67 members of the House of Representatives; 31 state governors; a Nobel Prize laureate; several Pulitzer Prize, Tony Award, and Emmy Award winners; and many more government officials, judges, business leaders, entertainers, and athletes. Fittingly, the university adopted Lee’s family motto: Non incautus futuri, which means “Not Unmindful of the Future.”

But Lee only had a chance to serve as the school’s president for a short time. In 1870, just five years after the Civil War ended, he suffered a stroke and died.

A Legacy Divided

The debate continues to this day: was Robert E. Lee a hero or a traitor? Although he was considered a war hero in the South, his peacetime promotion of reconciliation earned him accolades in the North. Shortly after the Civil War ended, Lee granted an interview to the New York Herald in which he condemned the assassination of President Lincoln as “deplorable,” said he “rejoiced” at the end of slavery, and referred to the North and the South as “we.” The Herald praised Lee’s efforts to reunite the nation: “Here in the North we have claimed him as one of ourselves.”

That sentiment was echoed by most American newspapers after Lee died in 1870, but not all of them. The editor of the New National Era, noted abolitionist and former slave, the great Frederick Douglass, wrote a scathing editorial: “We can scarcely take up a newspaper…that is not filled with nauseating flatteries of the late Robert E. Lee. Is it not about time that this bombastic laudation of the rebel chief should cease?”

But the adulation would only increase as the nation slowly healed from the wounds of the Civil War, and Jim Crow segregation laws became the norm in both the North and the South for another century. Lee’s legacy has been tied to U.S. race relations ever since.

Lee and Slavery

Like most wealthy white men in pre-Civil War America, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and even Ulysses S. Grant, Lee was a slave owner…but his own views on slavery were conflicted.

In 1856, he wrote:

There are few, I believe, in this enlightened age, who will not acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil. It is idle to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it is a greater evil to the white than to the colored race. While my feelings are strongly enlisted in behalf of the latter, my sympathies are more deeply engaged for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, physically, and socially. The painful discipline they are undergoing is necessary for their further instruction as a race, and will prepare them, I hope, for better things.

Lee even went so far as to advocate for the education of slaves, saying, “It would be better for the blacks and for the whites.” But he was not in favor of granting them the right to vote, and even said that if the slaves were freed, “I think it would be better for Virginia if she could get rid of them.” A deeply religious man, in Lee’s view slavery could only be ended by God.

The Man and the Mythology

Despite Lee’s views on slavery, his posthumous star kept rising. That began in earnest in 1871, the year after he died, with a biography called The Life of General Robert E. Lee, by John Cooke, a former Confederate soldier who served under Lee. Glossing over Confederate losses at Antietam and Gettysburg as having hastened the end of the war, Cooke focused on the “Lost Cause” belief that pervaded the South in the late 19th century. It downplayed slavery as the main cause of the Civil War and instead promoted the idea that the war was an “honorable, heroic struggle,” fought in defense of the Southern way of life and against Union attempts to disrupt it. And it was Lee, Cooke wrote, who kept the South united: “The crowning grace of this man, who was thus not only great but good, was the humility and trust in God, which lay at the foundation of his character.”

Hundreds of Lee biographies have been published since then, most of them painting the same rosy picture. For example, John Perry’s 2010 biography, Lee: A Life of Virtue, describes Lee as a “passionate patriot, caring son, devoted husband, doting father, don’t-tread-on-me Virginian, Godfearing Christian.” Perry wrote that the real Lee was a caring man who “considered it a special honor to push his invalid wife in her wheelchair. During the war, he picked wildflowers between battles and pressed them into letters to his family. He once described two dozen little girls dressed in white at a birthday party as the most beautiful thing he ever saw.”

Of course, today if a military leader were to defect from the United States and then lead a foreign army back into it, he would almost certainly be tried for treason and executed. But several former presidents—on both sides of the political spectrum—didn’t view Lee in that light.

- President Theodore Roosevelt said that the two greatest Americans of all time were George Washington and Robert E. Lee: “Lee was one of the noblest Americans who ever lived, and one of the greatest captains known to the annals of war.”

- Roosevelt’s cousin, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, called Lee “one of our greatest American Christians and one of our greatest American gentlemen.”

- President Woodrow Wilson, the first Southerner elected to the White House after the Civil War, wrote a biography praising Lee. He often told of his experience as a 13-year-old boy, shortly after the war in Augustus, Georgia, when he had the opportunity to stand next to Lee during a procession.

- After President Dwight D. Eisenhower was criticized for hanging a portrait of General Lee in the White House, he replied, “From deep conviction I simply say this: a nation of men of Lee’s caliber would be unconquerable in spirit and soul.”

- In 1975, a few years after a letter written by Lee to President Andrew Johnson requesting amnesty was discovered, President Gerald Ford finally restored Lee’s full U.S. citizenship. At the ceremony he said, “General Lee’s character has been an example to succeeding generations, making the restoration of his citizenship an event in which every American can take pride.”

- In 2009, President Barack Obama spoke at the annual dinner of the Alfalfa Club, which was founded in 1913 in honor of Lee (who, it turns out, is a distant relative of Obama’s). Noting the irony that Lee didn’t think African Americans should be allowed to vote or hold office, Obama said, “I know many of you are aware that this dinner began almost 100 years ago as a way to celebrate the birthday of General Robert E. Lee. If he were here with us tonight, the general would be 202 years old. And very confused.”

On the Other Hand…

Indeed, a lot of Americans in the 21st century are confused as to why Lee is still glorified.

- “Why is it so hard for people to just say Robert E. Lee fought for a despicable cause and doesn’t deserve our admiration?” asked Slate magazine’s chief political correspondent, Jamelle Bouie.

- Washington Post columnist Richard Cohen wrote, “It has taken a while, but it’s about time Robert E. Lee lost the Civil War. The South, of course, was defeated on the battlefield in 1865, yet the Lee legend—swaddled in myth, kitsch, and racism—has endured even past the civil rights era when it became both urgent and right to finally tell the ‘Lost Cause’ to get lost. Now it should be Lee’s turn. He was loyal to slavery and disloyal to his country—not worthy, even he might now admit, of the honors accorded him.”

The More Things Change

That’s one reason why so many schools and highways named after Lee have been renamed after prominent African Americans. But not all of them are being renamed. In 2015, after calls for the removal of the Confederate flag from Southern statehouses following a tragic church shooting by a white supremacist in South Carolina, a petition was started at Robert E. Lee High School in Staunton, Virginia, to change its name. The petition was met with strong opposition. In an official protest letter from students and alumni, they wrote, “We support the decision by South Carolina and other states to lower the Confederate flag, a symbol of bigotry and bias for many. But erasing Robert E. Lee’s name from the school is political correctness run amuck; and an act of historical vandalism.” The name wasn’t changed—that time—but it’s safe to say the battle isn’t over yet.

We’ll give the final word to Ulysses S. Grant, the general-turned-president who admired and then defeated Lee in the Civil War. In his memoir, he wrote about Lee’s surrender at Appomattox:

I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s OLD FAITHFUL 30th Anniversary Bathroom Reader. Uncle John and the Bathroom Readers’ Institute! Every year for the past three decades, Uncle John and his team of tireless researchers have delivered an epic tome packed with thousands of fascinating factoids. And now this extra-special 30th anniversary edition has everything you’ve come to expect from the BRI, and more! It’s stuffed with 512 pages of all-new articles sure to please everyone, from our longtime readers to newbies alike. You’ll get the scoop on the latest “scientific” studies, weird world news, surprising history, and obscure facts.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s OLD FAITHFUL 30th Anniversary Bathroom Reader. Uncle John and the Bathroom Readers’ Institute! Every year for the past three decades, Uncle John and his team of tireless researchers have delivered an epic tome packed with thousands of fascinating factoids. And now this extra-special 30th anniversary edition has everything you’ve come to expect from the BRI, and more! It’s stuffed with 512 pages of all-new articles sure to please everyone, from our longtime readers to newbies alike. You’ll get the scoop on the latest “scientific” studies, weird world news, surprising history, and obscure facts.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

“When the war ended, the two men went their separate ways, on either side of the Mason-Dixon Line (which ran between Virginia and Maryland, and divided the nation between North and South).”

The Mason-Dixon Line was nowhere near Virginia. It marked the border between Pennsylvania and Maryland, and also ran north-south to mark the border between Delaware and Maryland. It did divide “slave” states from “free” states, but only along it’s length.

The western end of the M-D line did mark part of the border between Virginia (the portion now known as “West Virginia”) and Pennsylvania, but the text in the article is wrong- no part of the Mason-Dixon line divide Virginia & Maryland.

Quick correction: While the Mason-Dixon line divided the nation between North and South, it runs between Maryland and Pennsylvania. Maryland and Virginia are separated by the Potomac River.

That’s why we’ve “The Border States” most markedly Maryland, which stand astride The South and North. Most Southerners consider these States as Northern. Of course, there are Territories, many of which produce offspring whom need History and Geography lessons, as they claim allegiances to particular “Sides” and, unbeknownst to them, having nothing to do with their State. Sorry, but when you hear about this at a N.C. University with a lot of Ohioans (my best mate and Long-Time Roommate hails from Columbus, so I’m not trying to be rude, merely citing my Source)

Anyway; the The Missouri Compromise saw the Territories (and Future US States) Maine & Missouri gain admission to the Union. This admittance maintained a balance between Free and Slave States. The Line drawn by The Comprise crosses across/sits on parallel 36°30 North, running from the southern borders of Kentucky & Virginia, and the northern border of what we know as the Texas Panhandle. The Compromise created, or tried to create, a demarcation zone, saying Chattle slavery could not breach this Line.

However, as is often forgotten, similar to the Emancipation Proclamation- see the: Time, Delivery, and use as a political tool, which didn’t end the Practice of Chattle Slavery {yes it existed} in the North- above the Line, and land East of the Pennsylvania Border. This remained the norm until 1865, with the ratification of the 13th Amendment to The U.S. Constitution.

But: The Mason-Dixon Line, 39°43 Parallel North, interestingly, established in the mid-1760s, established the borders of four States: Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and West Virginia.

The Line created by The Missouri Compromise runs about 200+ miles South of the Mason-Dixon Line. The use of certain Rivers indeed played a major role in establishing the Borders!

Thanks for that! As a Marylander, I’ve a correction: the Potomac divides Maryland and Virginia. The Mason-Dixon Line divides Maryland and Pennsylvania.