Sue Me, Sue You Blues

The business side of music can be a world of cutthroat legal practices and endless litigation. Here’s the story of one of the biggest music legal battles of all time.

The business side of music can be a world of cutthroat legal practices and endless litigation. Here’s the story of one of the biggest music legal battles of all time.

SOLO FLIGHT

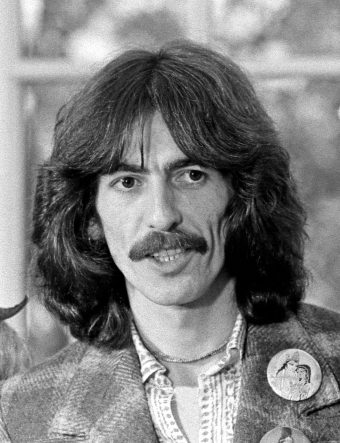

In 1969 George Harrison was on a break from the Beatles and was doing some concerts in Copenhagen, Denmark, with the group Delaney and Bonnie and Friends. One day he slipped out of a press conference, grabbed his guitar, and started playing some guitar chords that were in his head. Then he added in two religious chants: the Christian “hallelujah” and the Hindu “hare krishna.” Later he played it for the band, who joined in with four-part vocal harmony. Harrison fleshed out some verses about yearning to be closer to God, and titled it “My Sweet Lord.”

A week later, Harrison flew to London to help produce an album by singer/keyboardist Billy Preston and gave him “My Sweet Lord” to record. The song went nowhere, but Harrison decided to record it himself for his first post-Beatles album, All Things Must Pass. Released as a single, “My Sweet Lord” became a number-one hit in January 1971.

At the time of the song’s birth, Harrison thought elements of the song just popped into his head. He later figured out that subconsciously he’d been inspired by an old gospel song called “Oh Happy Day.” Harrison insisted he hadn’t “stolen” the song, he just used it as a starting point. And even if he had copied it directly, there were no legal ramifications—“Oh Happy Day” was in the public domain.

But as it would later turn out, another song did “pop” into Harrison’s head and subconsciously inspire him. And that one had serious legal ramifications.

COVER ME

As “My Sweet Lord” rose up the charts, a cover version was released by a group called the Belmonts (formerly Dion and the Belmonts, best known for the 1959 hit “A Teenager in Love”). But instead of a straight cover of Harrison’s song, the Belmonts’ version interspersed lyrics from “He’s So Fine,” a 1963 hit by the girl group the Chiffons. It was uncanny: The songs meshed together perfectly, with nearly the exact same chord structure and many of the same notes.

The Belmonts’ version was only a minor novelty hit. But it caught the attention of executives at Bright Tunes, the music publishing company that owned the copyright to “He’s So Fine.” In 1971 they sued Harrison, his label (Apple Records), and his publisher (Harrisongs Music Limited), claiming that Harrison had plagiarized “He’s So Fine” and turned it into “My Sweet Lord,” and was now profiting from it.

YOU NEVER GIVE ME YOUR MONEY

Guiding Harrison in the lawsuit was his business manager, Allen Klein. They’d worked together since early 1969, when Klein became the Beatles’ business manager. Klein handled the Beatles’ financial affairs shrewdly, saving Apple Records from bankruptcy, negotiating a new royalty rate ($.69 per album—the highest ever, at the time), and working for only a percentage of increased business. Nevertheless, Paul McCartney didn’t trust Klein (he had an abrasive demeanor and was rumored to engage in shady business practices), and never actually signed the contract authorizing Klein to make decisions for him—one of the many disagreements that led to the Beatles’ breakup in 1970.

Harrison tried to settle the suit quickly by offering to purchase the copyright to “He’s So Fine” (for an undisclosed sum, probably less than $100,000, which would be about $600,000 today), but despite being on the verge of bankruptcy, Bright Tunes declined. Reason: Klein had secretly met with Bright Tunes execs and told them they’d get more money by suing Harrison than by settling. He produced documents showing that Harrison stood to make more than $400,000 (about $2.4 million today) from “My Sweet Lord,” to which Klein told Bright Tunes that they had a right—and a shot in court—at ownership.

SOMETHING IN THE WAY HE SUES

Bright Tunes was in deep financial trouble at the time, and Klein likely knew it. A lengthy court battle would further deplete their funds, making Bright Tunes far more likely to settle for an offer— any offer—made for their back catalog. By encouraging Bright Tunes to sue Harrison, Klein was actually hoping to bring down the price on “He’s So Fine” so that he could buy the rights and sue Harrison for copyright infringement himself.

Unaware of Klein’s duplicity, Harrison was baffled when Bright Tunes declined his offer. Instead, they amended their lawsuit to request ownership of “My Sweet Lord” and half of all songwriting royalties earned by Harrison on the song, past and future. Harrison said no and the matter was headed for court.

I, ME, KLEIN

But in late 1971, before the case could be heard, Bright Tunes filed for bankruptcy (after they turned down another offer from Harrison—this time to buy their entire catalog). All legal matters would be delayed until the company was financially stable again.

Harrison’s camp was also in chaos. Earlier in 1971, Harrison had organized the Concert for Bangladesh. From the proceeds of the concert and album sales, nearly $10 million was raised for UNICEF to help refugees in the war-torn Asian nation. But little of it actually went to those in need. Klein, acting as Harrison’s business manager, should have arranged the donation with UNICEF prior to the concert or the album’s release, but he didn’t. Because of this, a hefty portion of the proceeds was taken out for taxes. And because it was reported after the fact, the IRS—and Harrison—suspected that Klein had embezzled some of the money. When Klein’s contract with Harrison expired in 1973, it wasn’t renewed.

In January 1976, nearly five years after the lawsuit was first initiated, Bright Tunes finally pulled itself out of bankruptcy. At that point Harrison offered Bright Tunes another deal: He would pay them $148,000 (40% of estimated royalties for “My Sweet Lord”) to settle the suit, but he would get to keep the copyright. Again—on the advice of secret collaborator Allen Klein—Bright Tunes turned it down and went to court in the hopes of more money. In the summer of 1976, the case finally went to trial.

MY SWEET LAWSUIT

Most of the trial was spent on testimony from musicologists (hired by both Bright Tunes and Harrison) who broke down and analyzed the basic musical elements of the two songs, “He’s So Fine” and “My Sweet Lord.” According to Bright Tunes’ experts, “He’s So Fine” used two musical motifs. Motif A is the notes G-E-D repeated four times. Motif B repeats the notes GA-C-A-C four times, with an extra “grace note” the fourth time. “My Sweet Lord,” they further argued, used the same Motif A the same four times, then Motif B three times instead of four. In place of the fourth repetition, “My Sweet Lord” used a passage of the same length with the same grace note in the same place. Each motif is fairly common, they said, but for both songs to use the two motifs together and for the same number of times was no accident.

HEAR YE

In August 1976, U.S. District Court judge Richard Owen delivered his verdict. “It’s perfectly obvious,” said Owen. “The two songs are virtually identical.” Owen went on to say, however, that he didn’t think Harrison intentionally stole “He’s So Fine.” He noted that there are only eight notes in the scale, and that “accidents do happen.” Though Harrison acknowledged being familiar with “He’s So Fine” (it was a massive hit), Owen said that while Harrison didn’t steal the song, he did infringe on the copyright. The difference: Harrison’s theft was unintentional or “subconscious.”

Nevertheless, Judge Owen ruled that a copyright had still been violated, a decision upheld on appeal with the court noting that United States copyright law does not require the showing of intent to infringe.

Monetary damages were decided three months later, in November 1976. The royalties for “My Sweet Lord”—based on the sales of singles, albums, and sheet music—totaled $2.1 million. But Bright wasn’t awarded the entire amount. Judge Owen determined that only 75 percent of the song’s merit and success was due to “He’s So Fine,” with the other 25 percent owing to Harrison’s lyrics and arrangement. So Owen recommended Bright get 75 percent of the royalties, about $1.6 million. Had Harrison been found to have intentionally stolen the song, Bright Tunes would probably have gotten the full amount.

After five years, the case was finally decided, but no money would change hands…yet.

HALLELUJAH

Shortly after the trial, Bright Tunes entered into an agreement to sell its entire catalog of songs—and their subsequent litigation rights—for $587,000 to music publisher ABKCO, a company owned by…Allen Klein. Still stinging from the Concert for Bangladesh scandal, Harrison refused to pay Klein the $1.6 million he owed Bright. By now, Harrison had become aware of Klein’s secret double-cross with Bright, and filed a motion with the court arguing that Klein was ineligible to get any money from “My Sweet Lord” because the plagiarism trial was the result of Klein’s illegal dealings.

It took another five years for that decision to be handed down. In February 1981, the U.S. District Court ruled that Klein had indeed illegally betrayed Harrison back in 1976, thereby compromising the integrity of the findings of the plagiarism suit. As a result, the financial terms from the case were ruled invalid, meaning Harrison didn’t have to pay anybody the $1.6 million in royalties.

WILL IT GO ROUND IN CIRCLES

The court also ruled that Harrison reimburse Klein $587,000. That’s what Klein paid for the Bright Tunes catalog. With Harrison paying that amount, Klein would break even—but not profit—from his purchase of the Bright Tunes catalog.

But there was yet another twist. The judge ruled that because of Klein’s machinations, and because Harrison would, in essence, end up paying for the Bright Tunes catalog, Harrison would be the sole owner of the copyright to “He’s So Fine.” After a decade-long legal battle, Harrison would own the song he’d inadvertently plagiarized years earlier.

AFTERMATH

Harrison channeled his anger and frustration over the suit into two hit songs, “This Song” and “Sue Me, Sue You Blues.” But the impact of the “My Sweet Lord” debacle was felt for years to come, in an explosion of pop-music plagiarism cases:

- The publishing company that owned the rights to the standard “Makin’ Whoopee” sued Yoko Ono for her song “Yes, I’m Your Angel.” She later admitted in court that she’d taken the melody and structure of the song, added new lyrics, and taken full credit.

- Jazz pianist Keith Jarrett sued Steely Dan for plagiarism on the title track of their album Gaucho, citing similarities to his composition “Long As You Know You’re Living Yours.” Future pressings of Gaucho credited Jarrett as a songwriter.

- The producers of Ghostbusters asked Huey Lewis to write the movie’s theme song. When he declined, Ray Parker Jr. was enlisted. Lewis later sued Parker for plagiarism because his song “Ghostbusters” sounded strikingly similar to Lewis’s “I Want a New Drug.” Parker paid Lewis an undisclosed amount, but alleged that the producers told him to write a song that sounded “like Huey Lewis.”

- Saul Zaentz of Fantasy Records owned the rights to all of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s songs. In 1985 he sued former CCR singer John Fogerty, claiming Fogerty’s song “The Old Man Down the Road” plagiarized CCR’s “Run Through the Jungle.” In other words, Zaentz sued Fogerty for sounding too much like himself. Fogerty won the case when the court ruled that an artist cannot plagiarize himself.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Triumphant 20th Anniversary Bathroom Reader. This behemoth of a book is jam-packed with 600 pages of all-new articles (as usual, divided by length for your sitting convenience). In what other single book could you find such a lively mix of surprising trivia, strange lawsuits, dumb crooks, origins of everyday things, forgotten history, quirky quotations, and wacky wordplay? Uncle John rules the world of information and humor, so get ready to be thoroughly entertained.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Triumphant 20th Anniversary Bathroom Reader. This behemoth of a book is jam-packed with 600 pages of all-new articles (as usual, divided by length for your sitting convenience). In what other single book could you find such a lively mix of surprising trivia, strange lawsuits, dumb crooks, origins of everyday things, forgotten history, quirky quotations, and wacky wordplay? Uncle John rules the world of information and humor, so get ready to be thoroughly entertained.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|