Dustbin of History: Project Greek Island

Here’s our look at one of the best-kept secrets of the Cold War…or was it? It depends on how you look at it.

Here’s our look at one of the best-kept secrets of the Cold War…or was it? It depends on how you look at it.

COOKING THE BOOKS

In 1980 a hotel executive named Ted Kleisner landed a job as the general manager of the Greenbrier, a five-star luxury resort in the Allegheny Mountains of West Virginia. The resort sprawls over 6,500 acres and includes hiking and biking trails, three championship golf courses, a hotel with over 600 rooms, more than 90 guest houses, and its own private train station. Learning to run such a large facility would have been a big job for anyone. Even so, it only took a few days for Kleisner to notice that there were some serious discrepancies in the company’s books. For example:

- The resort was spending a fortune on “maintenance” of equipment that it didn’t own.

- It had ordered thousands of gallons of diesel fuel that it had no need for. The fuel had disappeared without a trace.

- Every payday, dozens of paychecks were being mailed out to people whose names did not appear on the employee roster.

The deeper Kleisner dug, the more problems he found.

BENEATH THE SURFACE

Strangely, when Kleisner took his concerns to his superiors, they didn’t seem that concerned…until he talked about turning the matter over to the police.

That got their attention. Not long afterward, Kleisner was instructed to report to a building in a remote section of the grounds, where a man identifying himself as a senior Pentagon official invited him into an office. “He turned up a radio very loud and shut the blinds,” Kleisner recalled in a 1995 interview with the London Times. “Then he said, ‘You are about to be briefed on a top-secret government project that is part of the Greenbrier.’”

After Kleisner signed a pledge of secrecy, the official let him in on one of the most sensitive secrets of the Cold War era: 65 feet beneath the West Virginia wing of the Greenbrier was a fully staffed, fully operational bomb shelter large enough to accommodate both houses of the United States Congress, plus family members and key aides, for up to 60 days in the event of nuclear war.

SHELTER SHOCK

The shelter dated back to the late 1950s and was the brainchild of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. A former five-star general, Ike knew that the Pentagon was building numerous “emergency command relocation centers” for top military leaders (including himself), to ensure that they would survive a nuclear attack by the Soviet Union and would be able to continue to oversee the defense of whatever was left of the country.

But what would happen if the military leaders were the only top officials to survive a nuclear war? Eisenhower worried that America might slide into dictatorship. He believed that the United States had to put as much effort into building shelters for the legislative and judicial branches of the government as it did for the military and the commander-in-chief.

HIDE AND SEEK

One of the tricks to building an effective bomb shelter, especially one designed to house top government officials, is doing it in complete secrecy—the enemy can’t bomb it if they can’t even find it. But how do you hide a bomb shelter large enough to accommodate more than 1,000 people, plus all the food, supplies, machinery, and equipment necessary to keep them alive for 60 days?

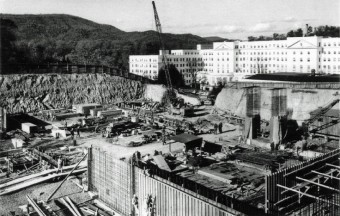

Eisenhower himself has been credited with being the one who came up with the idea of burying it beneath the Greenbrier resort. He had visited it a number of times over the years and liked to play golf there. The place had a lot going for it as the potential site for an important bomb shelter: It was 250 miles southwest of Washington, D.C., close enough to be accessible but far enough away to survive a nuclear strike against the city. Since it had its own train station, large numbers of people would be able to evacuate there in an emergency. Best of all, as Eisenhower learned, the Greenbrier was planning to add a giant new wing to the hotel.

At Eisenhower’s request, the Architect of the Capitol approached the owners of the resort with a deal: In exchange for allowing the government to build the bomb shelter underneath the new wing as it was being constructed, the government would pay for the wing as well as for the bunker. Because both would be built at the same time, the thinking went, the shelter wouldn’t attract much attention. Anyone who saw the work under way would naturally assume that it was all part of the hotel.

At Eisenhower’s request, the Architect of the Capitol approached the owners of the resort with a deal: In exchange for allowing the government to build the bomb shelter underneath the new wing as it was being constructed, the government would pay for the wing as well as for the bunker. Because both would be built at the same time, the thinking went, the shelter wouldn’t attract much attention. Anyone who saw the work under way would naturally assume that it was all part of the hotel.

Who could pass up an offer like that? The Greenbrier’s owners took the deal and work on “Project Greek Island,” as the bomb shelter was code-named, began in 1958.

YOUR TAX DOLLARS AT WORK

What kind of a bomb shelter would you build if you had the unlimited resources of the federal government behind you, and no public oversight thanks to the fact that the project was a secret? The bomb shelter built underneath the Greenbrier was enormous and had everything. The size of two football fields stacked one atop the other, it was more than 60 feet underground and protected by concrete walls and ceilings 5 feet thick. It had 153 rooms, including 18 dormitories that slept 60 people each; a kitchen and a cafeteria large enough to feed 400 people at a sitting, and a full hospital suite complete with two operating rooms, an intensive-care unit, a 12-bed ward, and a “pathological-waste incinerator” large enough to serve as a crematorium if the need arose. Thirty-five doctors and nurses would have staffed the hospital if it were ever activated.

The shelter also had its own air and water decontamination facilities and a power station stocked with 42,000 gallons of fuel, enough to keep the shelter’s giant diesel generators running for months on end. Giant steel and concrete blast doors protected the shelter’s four hidden entrances. The largest door, which protected a tunnel large enough to drive trucks into, weighed 40 tons.

HANG IN THERE

Maintaining contact with government and military officials in other secret bunkers during a nuclear war was a top priority, as was broadcasting messages of hope and encouragement to any survivors fending for themselves in post-nuclear-war America. To this end the shelter was also equipped with a sophisticated communications area, complete with telephone equipment and TV and radio broadcasting studios. Who knew when nuclear war might come? The TV studio had four different pull-down backdrops of the Capitol dome, one for each season of the year, so that elected officials would look in season when speaking to their constituents back home.

AN OPEN SECRET

The bomb shelter also contained two rooms large enough to serve as House and Senate chambers. A third, even larger room, would have served as office space for the officials and their aides, and was also large enough to host joint sessions of Congress if the need ever arose.

Unlike the rest of the bomb shelter, which was concealed behind a locked and carefully guarded door marked “Danger: High Voltage–Keep Out,” these large rooms were hidden in plain sight —they were open to the public and used by the Greenbrier as a basement exhibition hall. The only hint of the room’s true purpose was a movable, wallpapered panel next to the corridor leading to the hotel. The panel concealed a 25-ton blast door that was normally kept open to allow access to the hall. But if a crisis ever erupted, the public would have been hustled out of the exhibition hall (the shelter was stocked with firearms and riot gear for just such an occasion); then the blast door would have been closed and locked from inside the shelter, sealing its occupants off from Armageddon and abandoning the Greenbrier and its guests and staff to their fate.

Did you ever attend an exhibit or trade show in the basement of the Greenbrier? Or maybe you saw a movie in the Governor’s Hall? (The House chamber was disguised as a theater, and movies really were shown there.) If so, you were in one of the most secret bomb shelters in the world, and you didn’t even know it.

TRY NOT TO THINK ABOUT IT

For all its amenities, the bomb shelter was still a bomb shelter, after all, one designed to be used at what would probably have been the end of the world. The designers put a lot of thought into managing the psychological stresses the shelter occupants would undoubtedly be under if nuclear war ever came. Each of the 18 dormitory rooms had its own lounge stocked with books, magazines, an exercise bicycle, and a TV to provide distractions (though it’s unclear what people would have watched on postapocalyptic TV). To make the shelter seem less like an underground tomb, the walls of the cafeteria had fake “windows” that looked out onto painted landscapes. The pharmacy was stocked with plenty of antidepressants, and there was an isolation chamber to contain anyone who went completely nuts under the strain.

OPEN FOR BUSINESS

In all the shelter cost more than $10 million to build (about $80 million today), and the hotel wing on top of it cost another $4 million. Both projects were completed in October 1962—just in time for the shelter to be activated during the Cuban missile crisis, the only time in the shelter’s 30-year history that it went on full alert. At one point during the crisis the Senate and House of Representatives (and numerous crates of top-secret documents) came within 12 hours of relocating to the Greenbrier. That was as close as Project Greek Island ever came to actually being put to use.

In all the shelter cost more than $10 million to build (about $80 million today), and the hotel wing on top of it cost another $4 million. Both projects were completed in October 1962—just in time for the shelter to be activated during the Cuban missile crisis, the only time in the shelter’s 30-year history that it went on full alert. At one point during the crisis the Senate and House of Representatives (and numerous crates of top-secret documents) came within 12 hours of relocating to the Greenbrier. That was as close as Project Greek Island ever came to actually being put to use.

But just because the shelter was never put to use doesn’t mean that it wasn’t kept ready for use. For the next 30 years, 12 to 15 retired military personnel with high security clearances were always stationed at the Greenbrier, where they posed as TV repairmen working for a shell company called “Forsythe Associates.” To make their cover story believable, the “repairmen” really did spend as much as 20 percent of their time repairing TVs at the resort.

KEEPING IT FRESH

The rest of the time, they and a few dozen trusted Greenbrier employees who had been sworn to secrecy were down in the bunker maintaining equipment, replacing burned-out lightbulbs, changing bedsheets, restocking expired food and other supplies, and cleaning the 110 showers, 187 sinks, 167 toilets, and 74 urinals that were never used. They rotated the magazines and books in the lounges to keep the reading material fresh, and they kept the pharmacy stocked with the prescription medications of all 435 members of the House and Senate.

Once a year, they replaced outdated medical equipment so that the hospital kept up with advances in medicine. Because bed space in the dormitories was assigned by seniority, after each election the workers changed the name tags on the bunk beds as older politicians left office (or died) and younger ones moved up the ranks. They even turned the pages on the daily calendars scattered throughout the facility so that they would always show the correct date. If at any time in those 30 years the House and Senate had been forced to evacuate to the Greenbrier, it would have seemed as if the bomb shelter had just opened for business that morning.

SHHH!

So how secret was the bomb shelter? It depends on what you mean by secret. As far as anyone can tell, the people who signed secrecy pledges did honor their commitment. Not that they had much choice—they faced stiff fines and prison time if they talked. But you just can’t build a facility that big without it attracting some attention, if from no one else then at least from the construction workers who watched as 4,000 loads of concrete, more than 50,000 tons in all, were hauled up to the site and poured to make five-foot-thick walls and ceilings in a “basement” that was 65 feet underground. How many hotel basements are 65 feet underground? How many have five-foot-thick walls and ceilings? Even if the workers didn’t know what they were building, they knew it was something unusual, and by the time the project was finished the entire valley buzzed with gossip and speculation.

At one point the government became so concerned about how much the locals might have pieced together about the site that they sent two agents who knew nothing about it to the area posing as hunters to see how much information they could pry out of the locals. According to one version of the story, they returned with so much information about the bomb shelter that the government had to give them top-secret security clearances.

One thing that helped to keep the secret from traveling outside of the area was the fact that with more than 1,500 employees, the Greenbrier wasn’t just the largest employer in the valley, it was pretty much the only one of any significance in the entire county. Even if you didn’t work there you knew someone or were related to someone who did. People gossiped about the facility with each other (and with the occasional nosy hunter), but somehow the story never got much farther than that. The world outside Greenbrier County remained almost completely in the dark.

BLAME IT ON THE MEDIA

Project Greek Island remained a secret (if you can call it that) until May 1992, when the Washington Post revealed its existence in an exposé. By then the Cold War had been over for several months—the Soviet Union passed into history on Christmas Day 1991—and the bomb shelter had fulfilled its purpose. Rather than deny the Post story, the Pentagon acknowledged the shelter’s existence…and then promptly shut it down. Ownership of the facility reverted to the Greenbrier, which converted half of it into a data-storage facility and opened the rest to public tours…for now, anyway: At last report the resort was thinking about turning it into a casino with a James Bond theme.

DOWN UNDER

The United States isn’t the only country that sank a lot of time and money into holes in the ground for top government officials: The British government built an entire underground city, complete with two train stations, 60 miles of road, and one pub in a rock quarry 70 miles outside of London. Canada built a network of seven “Diefenbunkers” (nicknamed in honor of Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, who had them built) outside of major cities around Canada.

WHITE ELEPHANT

When the Cold War ended, these countries learned the same lesson that the U.S. did: It’s a lot easier to build giant underground facilities with five-foot concrete walls than it is to figure out what to do with them when you’re done with them. The British site has been for sale since 2005; the Canadians did manage to sell off one Diefenbunker in Alberta, but when rumors spread that the new owner was thinking about reselling it to a biker gang, the government bought it back and demolished it.

And even though the Cold War has long been over, the threat of a nuclear attack on Washington, D.C., remains. Chances are there’s another hi-tech, high-luxury bunker located somewhere on the outskirts of the nation’s capitol…that hopefully will never have to be put to use.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Triumphant 20th Anniversary Bathroom Reader. This behemoth of a book is jam-packed with 600 pages of all-new articles (as usual, divided by length for your sitting convenience). In what other single book could you find such a lively mix of surprising trivia, strange lawsuits, dumb crooks, origins of everyday things, forgotten history, quirky quotations, and wacky wordplay? Uncle John rules the world of information and humor, so get ready to be thoroughly entertained.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Triumphant 20th Anniversary Bathroom Reader. This behemoth of a book is jam-packed with 600 pages of all-new articles (as usual, divided by length for your sitting convenience). In what other single book could you find such a lively mix of surprising trivia, strange lawsuits, dumb crooks, origins of everyday things, forgotten history, quirky quotations, and wacky wordplay? Uncle John rules the world of information and humor, so get ready to be thoroughly entertained.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

60 days? Wow, they really wanted to make sure everybody there would easily survive a full out nuclear war LOL