The Story Behind The Godfather

The Godfather is considered one of the best movies ever made—the American Film Institute ranks it #3, after Citizen Kane and Casablanca. The story of how it got made is just as good.

The Godfather is considered one of the best movies ever made—the American Film Institute ranks it #3, after Citizen Kane and Casablanca. The story of how it got made is just as good.

BOOKMAKER

In 1955 a pulp-fiction writer named Mario Puzo published his first novel, The Dark Arena, about an ex-GI and his German girlfriend who live in Germany after the end of World War II. The critics praised it, but it didn’t sell very many copies.

It took Puzo nine years to finish his next novel, The Fortunate Pilgrim, which told the story of an Italian immigrant named Lucia Santa who lives in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood of New York City. After two bad marriages, Lucia is raising her kids alone and worries about her daughter, who has become too Americanized, and her son, who is being pulled into the Mafia.

Today The Fortunate Pilgrim is widely considered a classic work of Italian American fiction; Puzo himself considered it the best book he ever wrote. But it sold as poorly as The Dark Arena—together the two books had earned Puzo only about $6,500. By then he was 45 years old, $20,000 in debt, and tired of being broke. He wanted his next novel to be a success. “I looked around and said…I’d better make some money,” he recalled years later.

HIT MAN

Puzo figured that a story with an entire family of gangsters in it instead of only one would have more commercial appeal than The Fortunate Pilgrim had. He titled his third novel Mafia, and in a sign of how his fortunes were about to change, he received a $5,000 advance payment from the publisher. Then, after he’d completed only an outline and 114 pages, Paramount Pictures acquired the movie rights for $12,000 and agreed to pay an additional $50,000 if the movie actually got made.

Puzo’s decision to pack his story with wiseguys paid off. Mafia, by now retitled The Godfather, was a publishing phenomenon. The most successful novel of the 1970s, it spent 67 weeks on the bestseller list and sold more than 21 million copies before it even made it to the big screen.

THE NUMBERS RACKET

Believe it or not, the success of the novel actually hurt its chances of becoming a decent film. Bestsellers appeal to movie studios because they have a guaranteed audience. But fans will come to the theater no matter what, so why spend extra money to get them there? Shortsighted studio executives are often tempted to maximize profits by spending as little on such movies as possible. At the time Paramount was in bad financial shape and its last Mafia film, The Brotherhood, starring Kirk Douglas, bombed. The studio couldn’t afford another expensive mistake. It set the budget for The Godfather at $2 million, a minuscule figure even for the early 1970s.

Two million dollars wasn’t enough money to make a decent film set in the present, let alone a period piece like The Godfather, which takes place from 1945 to 1955—and in Manhattan, one of the most expensive places in the country to shoot a film. To save on expenses, Paramount decided to move the story forward to the 1970s, and made plans to film it in a Midwestern city like Kansas City, or on the studio back lot instead of on actual New York streets. The title would still be The Godfather, but other than that the film would have very little in common with Puzo’s novel.

Paramount signed Albert Ruddy, one of the co-creators of TV’s Hogan’s Heroes, to produce the film. Ruddy had produced only three motion pictures, and they’d all lost money, but what impressed the studio was that he had brought them in under budget. That was what Paramount was looking for in The Godfather—a critical flop that would nonetheless turn a quick profit because it had a built-in audience and would be filmed on the cheap.

NO, THANKS

By now it was clear in Hollywood that the studio was planning what was little more than a cinematic mugging of millions of fans of Puzo’s novel. What director would want to work on something like that? It was enough to ruin a career. Ruddy approached several big directors about making the film but, of course, none were interested. So he turned to a hungry young director named Francis Ford Coppola.

He turned it down, too.

THE KID

In his short career, Coppola, then 31, had directed only four films (not including the nudie flicks he worked on while studying film at UCLA): Dimentia 13, a critical flop that bombed at the box office; Finian’s Rainbow, another critical flop that bombed; You’re a Big Boy Now, another critical flop that bombed; and The Rain People (starring James Caan and Robert Duvall), a critical success that bombed. With his track record, he couldn’t afford to be too choosy, and yet when Albert Ruddy offered him The Godfather in the spring of 1970, Coppola picked up a copy of the book and read only as far as one particularly lurid scene early in the book before he dismissed the whole work as a piece of trash and told Ruddy to find someone else. (Have you read the book? It’s the part where Sonny’s mistress goes to a plastic surgeon to have her “plumbing” fixed and ends up having an affair with the doctor.)

In his short career, Coppola, then 31, had directed only four films (not including the nudie flicks he worked on while studying film at UCLA): Dimentia 13, a critical flop that bombed at the box office; Finian’s Rainbow, another critical flop that bombed; You’re a Big Boy Now, another critical flop that bombed; and The Rain People (starring James Caan and Robert Duvall), a critical success that bombed. With his track record, he couldn’t afford to be too choosy, and yet when Albert Ruddy offered him The Godfather in the spring of 1970, Coppola picked up a copy of the book and read only as far as one particularly lurid scene early in the book before he dismissed the whole work as a piece of trash and told Ruddy to find someone else. (Have you read the book? It’s the part where Sonny’s mistress goes to a plastic surgeon to have her “plumbing” fixed and ends up having an affair with the doctor.)

AN OFFER HE COULDN’T REFUSE

Film buffs know that we have George Lucas to thank for Star Wars. We can thank him for The Godfather, too. In November 1969, Coppola had founded his own film company, American Zoetrope, and its first project was to turn his friend George’s student film, THX-1138, into a feature-length movie. Today it’s a cult classic, but it was such a dud when it was first released that it nearly forced American Zoetrope into bankruptcy. Coppola was so desperate to keep the studio’s doors open that when Ruddy offered him the Godfather job a second time in late 1970, he agreed to at least give the novel another look.

This time Coppola read the book all the way through. He found more sections that he didn’t like, but he was also captivated by the central story of the relationship between the Godfather, Don Corleone, and his three sons. He realized that if he could strip away the lurid parts and focus on the central characters, The Godfather had a shot at becoming a very good film.

THE SALESMAN

If The Godfather had a shot at becoming a good movie, it was a very long shot indeed. Robert Evans, Paramount’s vice president in charge of production, wasn’t sure he wanted Francis Ford Coppola for the director’s job, and Coppola was willing to do it only if he got a big enough budget to direct the film that he wanted to direct: a period piece, shot on location in the United States and Sicily, and faithful to the novel.

If you could boil Coppola’s entire career down to the single moment that put him on the path to his future successes, it must have been the meeting he had with Evans and Stanley Jaffe, the president of Paramount, to win final approval to direct The Godfather. When producer Albert Ruddy picked Coppola up at the airport to take him to the meeting, he peppered the young director with all the arguments the studio heads were going to need to hear: He could finish the picture on time, he could keep within the budget, etc.

Coppola considered all this and then decided to go his own way.

REVERSAL OF FORTUNE

Rather than talk about schedules and finances, as soon as the meeting began, Coppola launched into a vivid and passionate description of the characters and the story as he thought they should be portrayed. “Ten minutes into the meeting he was up on the f*#$%ing table, giving one of the great sales jobs of all time for the film as he saw it,” Ruddy told Harlan Lebo in The Godfather Legacy. “That was the first time I had ever seen the Francis the world got to know—a bigger-than-life character. They couldn’t believe what they were hearing—it was phenomenal.”

Evans and Jaffe were floored. “Francis made Billy Graham look like Don Knotts,” Evans remembered. On the strength of that one meeting with Coppola, Evans and Jaffe abandoned the idea of a “quickie mobster flick,” increased The Godfather’s budget to $6 million (it would later grow to $6.5 million), and announced that it would be Paramount’s “big picture of 1971.”

CASTING CALL

Getting Paramount to take The Godfather seriously would come at a price—now that the studio had so much money tied up in the film, it was determined to oversee every big decision. Take casting: Even when he was writing the novel, Mario Puzo had pictured Marlon Brando playing the Godfather, Don Corleone, and Coppola agreed that he was perfect for the part. Though he was widely considered one of the world’s best actors, Brando had been in a rut for more than a decade; he had appeared in one money-losing film after another and had a reputation for being the most difficult actor in Hollywood. When he made his directorial debut in the 1961 film One-Eyed Jacks, his antics caused so many delays that production costs doubled and the film lost a bundle of money.

Paramount had produced One Eyed Jacks, and it wasn’t about to make the same mistake again. “As long as I’m president of the studio,” Jaffe told Coppola, “Marlon Brando will not be in this picture, and I will no longer allow you to discuss it.” The studio wanted someone like Anthony Quinn to play the part; Ernest Borgnine was the Mafia’s top pick for the job (according to FBI wiretaps). Rudy Vallee wanted the job; so did Danny Thomas. Mario Puzo remembered reading in the newspaper that Thomas wanted the part so badly that he was willing to buy Paramount to get it. The thought of that happening put Puzo into such a panic that he wrote Brando a letter begging him to take the part.

I’LL MAKE HIM AN OFFER HE CAN’T ACCEPT

Coppola was as determined to get Brando as Puzo was. He pushed Jaffe so hard, in fact, that Jaffe finally put him off by agreeing to “consider” Brando, but only if the World’s Greatest Actor agreed to three conditions that Jaffe was certain he would never accept: Brando had to agree to work for much less money than usual, he had to pay for any production delays he caused out of his own pocket, and he had to submit to a screen test, something he knew Brando would see as a slap in the face.

MAKING THE MAN

Coppola gave in—what choice did he have? While all this was going on, Brando read both the book and the script and became interested in playing the part. Coppola didn’t tell him about Jaffe’s conditions; Coppola just asked if he could come over and film a “makeup test.” Brando agreed.

At their meeting, Brando told Coppola he thought the Godfather should look “like a bulldog.” He stuffed his cheeks with tissues, slouched a little, and feigned a tired expression on his face. Then he started mumbling dialog. That may not sound like much, but with these and other subtle techniques, the 47-year-old actor turned himself into an old Mafia don. The change was so complete that when Coppola brought Brando’s test back to Paramount, Ruddy and the other studio executives didn’t even realize it was him. The “makeup test” closed the deal—Brando not only could play Don Corleone, the executives decided, he had to play him.

GET SHORTY

Coppola also had someone in mind to play the character of the Don’s youngest son, Michael Corleone. He’d recently seen a play called Does the Tiger Wear a Necktie?, a story about a psychotic killer, and he was convinced that the star of the play, 31-year-old Al Pacino, was just the guy for the part. Pacino was beginning to make a name for himself on Broadway, but he was still largely unknown to movie audiences.

Paramount wouldn’t hear of it. Pacino was a nobody, the studio complained. The part of Michael Corleone was as big a part as Brando’s, and studio wanted someone with star power to fill it. Pacino was too short, they argued. (He’s about 5’6″ tall). The son of Sicilian immigrants, Pacino looked “too Italian” to play the son of a Sicilian mobster, the executives argued. Dustin Hoffman was interested, and names like Jack Nicholson, Warren Beatty, Ryan O’Neal, and even Robert Redford were also being tossed around. O’Neal and Redford didn’t look anything like Italians, but they were big stars. Paramount figured they could pass as “northern Italians.”

THOSE EYES

Coppola had his heart set on Al Pacino for the role of Michael Corleone, and, as he had with Marlon Brando, he just kept pushing until he finally got his way. Paramount forced him to test other actors for the part, and every time he did he had Pacino come in and do another screen test, too. Robert Evans got so sick of seeing Pacino’s face that he screamed, “Why the hell are you testing him again? The man’s a midget!”

But Coppola would not back down, not even when Pacino grew discouraged filming test after test after test for a part that he knew the studio would never give him. Ironically, it may have been that very frustration that got Pacino the part—in some of the screen tests he appears calm but also seems to be hiding anger just below the surface. This moody intensity was an accurate reflection of his state of mind, and it was just the quality he needed to convey to be successful in the role.

Did the screen tests convince Paramount that Pacino was right for the part, or did Coppola finally just wear them down? Whatever it was, Pacino got the job. “Francis was the most effective fighter against the studio hierarchy I’ve ever seen,” casting director Fred Roos told one interviewer. “He did not do it by yelling or screaming, but by sheer force of will.”

YOU LOSE SOME, YOU WIN SOME

By the time Paramount finally got around to approving Pacino for the role, he’d signed up to do another film called The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight. To get him out of that commitment, Coppola made a trade: He released another young actor from appearing in The Godfather so that he could take Pacino’s place in The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight. The actor: Robert De Niro—he’d been cast as Paulie Gatto, the driver and bodyguard who betrays Don Corleone. Losing the part may have been disappointing to De Niro at the time, but it also cleared the way for him to play the young Vito Corleone in The Godfather: Part II, the role that won him his first Oscar, for Best Supporting Actor, and made him an international star.

FAMILY PROBLEMS

As if fighting Paramount wasn’t bad enough, Coppola also had to contend with the real-life Mafia, which wasn’t too pleased with the idea of a big-budget Italian gangster movie coming to the screen. Joe Colombo, head of one of the real “five families” that made up the New York mob, was also the founder of a group called the Italian-American Civil Rights League, an organization that lobbied against negative Italian stereotypes in the media.

The League had won some impressive victories in recent years, successfully lobbying newspapers, broadcast networks, and even the Nixon Justice Department to replace terms like “the Mafia” and “La Cosa Nostra” with more ethnically neutral terms like “the Mob,” “the syndicate,” and “the underworld.” The League was at the height of its powers in the early 1970s, and now it set its sights on The Godfather.

I’M-A GONNA DIE!

How would you deal with the Maf…er, um…the “syndicate” if they were trying to stop the project you were working on? Albert Ruddy, the producer, decided to face the problem head on: He met with Colombo in the League’s offices to discuss mutual concerns, and he even let Colombo have a peek at the script. Colombo’s demands actually turned out to be fairly reasonable: He didn’t want the film to contain any patronizing Italian stereotypes or accents—“I’m-a gonna shoot-a you now”—and he didn’t want the Mafia identified by that name in the film. Ruddy assured Colombo that Coppola had no plans to use that kind of speech, and he even promised to remove all references to “the Mafia” from the script.

Colombo didn’t know it at the time, but removing the word “Mafia” from the script was an easy promise to keep because it wasn’t in there to begin with—guys who are in the Mafia don’t sit around discussing it by name.

In effect, Colombo had agreed to end the Mob’s opposition to the film and even to make some of his “boys” available for crowd control and other odd jobs, and had gotten next to nothing in return.

(In 1971, during filming of The Godfather, Colombo was gunned down in a Mob hit and lingered in a coma until 1978, when he finally died from his wounds.)

LASHED TO THE MAST

One of the nice things about winning so many battles with studio executives is getting to make the film you want to make; the bad thing is that once it becomes your baby, if things start to go wrong it’s easy for the studio to figure out who they need to fire—you.

Filming of The Godfather got off to a rough start—Brando’s performances in his first scenes were so dull and uninspired that Coppola had to set aside time to film them again. Al Pacino’s earliest scenes didn’t look all that promising, either. His first scenes were the ones at the beginning of the film, when he’s a boyish war hero determined to stay out of the family “business.” Pacino played the scenes true to character—so true, in fact, that when the Paramount executives saw the early footage, they doubted he’d be able to pass as a Mafia don.

For a time the set was awash with rumors that Coppola and Pacino were both about to be fired. How true were the rumors? Both men were convinced their days were numbered—that was one of the reasons Coppola cast his sister, Talia Shire, as Don Corleone’s daughter, Connie: He figured that if he was going to lose his job, at least she’d get something out of the film.

FAIR-WEATHER FRIENDS

More than 30 years later, it’s difficult to say how true the rumors were, especially now that the film is considered a classic—the executives who would have wanted to fire the pair back then are now more likely to take credit for discovering them. But the threat was real, and Marlon Brando saved Coppola by counter-threatening to walk off the job if Coppola was removed from the film.

Al Pacino saved his own skin when he filmed the scene where he murders Virgil Sollozzo and Captain McCluskey (Al Lettieri and Sterling Hayden) in an Italian restaurant. That was the first scene in which he got the chance to appear as a cold-blooded killer, and he pulled it off with ease. Finally, Paramount could see that he could indeed play a Mafia don.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Once these early problems were resolved, the production made steady progress and remained more or less on schedule and on budget. Marlon Brando behaved himself on the set and delivered one of the greatest performances of his career; the other actors gave excellent performances as well. As Paramount executives reviewed the footage after each day of shooting, it soon became clear to everyone involved that The Godfather was going to be a remarkable film.

In 62 days of shooting, Coppola filmed more than 90 hours of footage, which he and six editors whittled down to a film that was just under three hours long. (Paramount made Coppola edit it down to two and a half hours, but that version left out so many good scenes that the studio decided to use Coppola’s original cut.) By the time they finished—and before the film even made it into the theaters—The Godfather had already turned a profit: So many theaters rushed to book it in advance that it had already taken in twice as much money as it had cost to make.

LARGER THAN LIFE

The advance bookings were the first sign that The Godfather was going to do really big business; another sign came on March 15, 1972, the day the film premiered in the United States. That morning when Albert Ruddy drove into work, he saw people waiting in front of a theater that was showing The Godfather. It was only 8:15 a.m., and the first showing was hours away, but the fans were already lining up around the block—not just at that theater, but everywhere else in America, too.

The long lines continued for weeks. As The Godfather showed to one sold-out audience after another, it smashed just about every box-office record there was: In April it became the first movie to earn more than $1 million in a day; in September it became the most profitable Hollywood film ever made, earning more money in six months than the previous record holder, Gone With the Wind, had earned in 33 years. In all, it made more than $85 million during its initial release. (How long did it hold the record as Hollywood’s most profitable film? Only one year—The Exorcist made even more money in 1973.)

Nominated for 10 Academy Awards, The Godfather won for Best Actor (Brando), Best Adapted Screenplay (Coppola and Puzo), and Best Picture.

The Godfather revived Marlon Brando’s career and launched those of Francis Ford Coppola, Al Pacino, Robert Duvall, Diane Keaton, James Caan, Talia Shire, and even Abe Vigoda (who later starred in TV’s Barney Miller and Fish), whom Coppola discovered during an open casting call. “The thing that I like most about the film’s success is that everyone that busted their hump on this movie came out with something very special—and good careers,” Albert Ruddy said years later. “All of these people came together in one magic moment, and it was the turn in everybody’s careers. It was just a fantastic thing.”

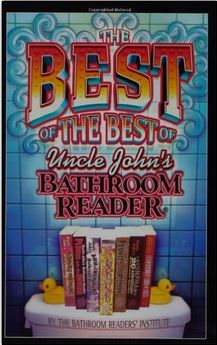

This article is reprinted with permission from The Best of the Best of Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader. They’ve stuffed the best stuff they’ve ever written into 576 glorious pages. Result: pure bathroom-reading bliss! You’re just a few clicks away from the most hilarious, head-scratching material that has made Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader an unparalleled publishing phenomenon.

This article is reprinted with permission from The Best of the Best of Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader. They’ve stuffed the best stuff they’ve ever written into 576 glorious pages. Result: pure bathroom-reading bliss! You’re just a few clicks away from the most hilarious, head-scratching material that has made Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader an unparalleled publishing phenomenon.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Thank you for that article. Two of my favorite movies of all-time, “Godfather” one and two. I think two is better, and as many times as I’ve watched them, I still get teary-eyed when Fredo gets capped.