Just Have One More Try – The Amazing Story of Douglas Mawson’s 300-Mile Antarctic Trek

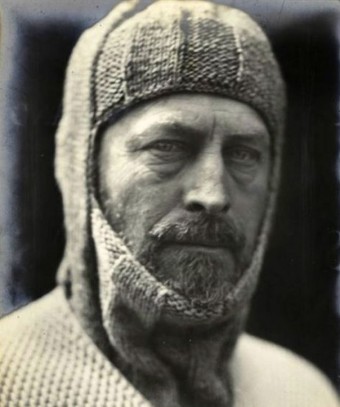

On a brutal Antarctic day in January 1913, without food, dogs, transport or companionship, starving, covered in open sores and with the soles of his feet attached to his body with only tape, 30-year-old Australian geologist and explorer Douglas Mawson’s only remaining motivation for soldiering on was to leave his diary in a place where searchers might eventually find it.

On a brutal Antarctic day in January 1913, without food, dogs, transport or companionship, starving, covered in open sores and with the soles of his feet attached to his body with only tape, 30-year-old Australian geologist and explorer Douglas Mawson’s only remaining motivation for soldiering on was to leave his diary in a place where searchers might eventually find it.

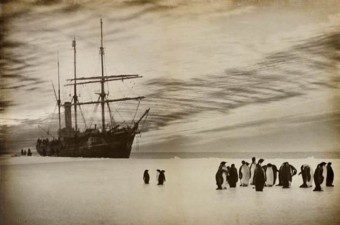

Mawson’s journey through hell had, ironically, begun rather auspiciously. As the leader of Australasian Antarctic Expedition, Mawson and his 31-man crew landed on January 8, 1912 at a place they named Cape Denison on Commonwealth Bay, a site later found to be the windiest sea-level place on Earth, with the average wind speeds ringing in at a whopping 50 mph (80 km/h). The crew established a base there, essentially a hut on a rocky cape, as well as another to the west on the Queen Mary Land ice shelf. Their relief ship, the Aurora, was not scheduled to return until January 15, 1914.

Well-provisioned, the men survived the coming winter which featured blizzards with wind speeds topping out at close to 200 mph (322 km/h). Mawson said of having to go outside in some of these, “A plunge into the writhing storm-whirl stamps upon the senses an indelible and awful impression seldom equalled in the whole gamut of natural experience. The world a void: grisly, fierce and appalling. We stumble and struggle through the Stygian gloom; the merciless blast – an incubus of vengeance – stabs, buffets and freezes; the stinging drift blinds and chokes.”

As the year went on and the storms waned, they prepared to take advantage of the (relatively) pleasant Antarctic summer, which lasts from around late November through February, to explore the previously uncharted, surrounding territory. Splitting into eight 3-man teams (with the remaining crew staying behind to tend the camps), Mawson’s Far Eastern Party included a Swiss skiing champion, 29-year old Xavier Mertz, and a member of the British Royal Fusiliers, 25-year old Belgrave Ninnis.

Setting off on November 10, 1912, Mawson’s party made great time, and a month later, they were 300 miles from Camp Denison. Having crossed two glaciers and dozens of deadly crevasses (where thin bridges of snow spanned and often hid the abyss below), the men were beginning to think of heading back (needing to return at the latest by January 15th, when the Aurora would arrive to pick them up). But then tragedy struck on December 14, 1912.

Setting off on November 10, 1912, Mawson’s party made great time, and a month later, they were 300 miles from Camp Denison. Having crossed two glaciers and dozens of deadly crevasses (where thin bridges of snow spanned and often hid the abyss below), the men were beginning to think of heading back (needing to return at the latest by January 15th, when the Aurora would arrive to pick them up). But then tragedy struck on December 14, 1912.

At about noon, Mertz, who skied ahead as a scout for the other two who were driving sledges pulled by Huskies, stopped and signaled that another crevasse was in their path. In the lead, Mawson had no trouble traversing a discovered snow bridge, and then glanced back to make sure Ninnis had adjusted his path to follow the safe course behind him. He had.

Pushing on and facing front, Mawson was surprised to suddenly notice Mertz had stopped and was heading back toward him, looking alarmed. Looking back himself, Mawson was shocked to see no sign of Ninnis, his sledge, or his six dogs. Rushing back on foot alongside Mertz, together the two soon reached an 11-foot hole in the surface of the snow, with two sets of tracks leading up to it, and only one leading away.

Taking turns roping up and creeping to the delicate lip of the hole, they leaned over the edge in an attempt to find their companion. However, the only survivor they saw was a suffering dog, as well as a dead one, both approximately 150 feet below the surface. Despite three-hours of desperate calling and listening, there was no sign of Ninnis, and with too little rope to reach even the 150 foot shelf, they had to accept that Ninnis was lost.

Poor planning made things worse. You see, rather than divvy up the supplies evenly between the two sleds, Ninnis’ sled had contained their three-man tent, most of the people food (all but 10 days rations), all of the dog food, and their six best dogs.

The men turned their sledge runners, Mertz’ skis and a spare tent cover into an improvised, cramped tent and spent that first, desperate night planning their 315 mile return journey.

Over the first few days, while they and the dogs were still relatively well nourished, they made good time on the trek back. However, between the limited food and constant exertion, during the remaining weeks of December, their huskies began dropping from exhaustion. As each dog could no longer run, it was placed on the sledge and carried along until they camped. Once the men made camp for the night, the no longer useful dog was killed and butchered, with its meat and offal becoming food for the men, with whatever was left being given to the remaining dogs. Nothing was wasted. Even the dogs’ toughened paws were ultimately stewed and eaten.

Unfortunately for the pair, they didn’t know that Husky liver is extremely high in Vitamin A (a nutrient that in excessive quantities can lead to severe health problems) and they kept choice bits like that for themselves.

The two men were soon down to one dog, so they harnessed themselves and also began to pull with her through the deep hard snow. Keeping only the most basic of gear, they threw away their rifle, extra runners, alpine rope, and even the camera and film they had used to memorialize their journey.

Sixteen days into their return journey and only a little over half way back, Mawson noted, “Xavier off colour. We did 15 miles, halting at about 9 am. He turned in – all his things very wet. The continuous drift does not give one a chance to dry a thing, and our gear is deplorable. Tent has dripped terribly, all caked with ice.”

Emaciated and seemingly suffering from hypervitaminosis A, Mertz quickly began to decline; on January 5, 1913, at least slightly delusional, in an attempt to prove to Mawson that his fingers were not frostbitten, he actually bit of the tip of one. Soon after, he refused to go any further.

Mawson would not leave Mertz behind and persuaded him to ride on the sledge, now pulled solely by himself.

Although they had now travelled two-thirds of the way back, on January 7, 1913, they still had 100 miles to go, and Mertz was in his last hours. Mawson stated,

During the afternoon he has several fits and is delirious, fills his trousers again and I clean out for him. He is very weak, becomes more and more delirious, rarely being able to speak coherently. At 8 pm he raves and breaks a tent pole. I hold him down, then he becomes more peaceful and I put him quietly in the bag. He dies peacefully at about 2 am on the morning of the 8th. He had lost all the skin of his legs and private parts. I am in same condition and sore on finger won’t heal.

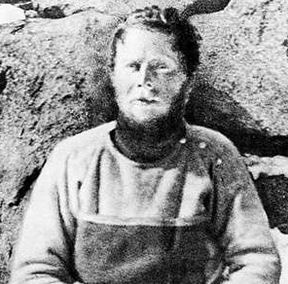

Now alone in one of the loneliest places on Earth, Mawson made a snow block cairn for Mertz, cut the sledge in half and constructed a “sail” out of Mertz’ coat and some other remaining cloth and continued on, with nearly no food, his hair falling out in clumps, skin peeling off of his legs, and open sores on his face and body. Within a few days, he also discovered to his horror that the soles of his feet had detached, but, ever-persistent, he taped them back on, put on several pairs of wool socks and soldiered on.

Now alone in one of the loneliest places on Earth, Mawson made a snow block cairn for Mertz, cut the sledge in half and constructed a “sail” out of Mertz’ coat and some other remaining cloth and continued on, with nearly no food, his hair falling out in clumps, skin peeling off of his legs, and open sores on his face and body. Within a few days, he also discovered to his horror that the soles of his feet had detached, but, ever-persistent, he taped them back on, put on several pairs of wool socks and soldiered on.

With 80 miles to go and only a few days to make the January 15th rendezvous with the Aurora, Mawson’s chances were looking increasingly bleak when yet another disaster struck. Breaking through a bridge, he found himself suspended from his sledge over a deadly crevasse, kept from falling only by his harness rope.

Luckily, the sledge was firmly stuck, and the rope had knots periodically along its 14-foot length. Summoning his remaining strength, Mawson lunged for the first knot, grabbed and pulled his body up. Repeating the feat again and again, with his physical and mental strength exhausted, Mawson finally reached the lip of the crevasse – at which point he slipped and plunged back down, again only saved by his harness.

Emotionally, figuratively and literally at the end of his rope, Mawson was considering untying himself and just ending it all by falling into the crevasse.

Below was a black chasm. Exhausted, weak and chilled (for my hands were bare and pounds of snow had got inside my clothing) I hung with the firm conviction that all was over except the passing. It would be but the work of a moment to slip from the harness, then all the pain and toil would be over.

But then he recalled a verse from Robert Service’s poem, The Quitter: “Just have one more try – it’s dead easy to die, It’s the keeping-on-living that’s hard.”

Giving it “one last tremendous effort,” Mawson again climbed the rope. “My strength was ebbing fast; in a few moments it would be too late. The struggle occupied some time, but by a miracle I rose slowly to the surface. This time I emerged feet first…and pushed myself out…Then came the reaction, and I could do nothing for quite an hour…”

And later, “For hours I lay in the bag, rolling over in my mind all that lay behind and the chance of the future. I seemed to stand alone on the wide shores of the world…My physical condition was such that I felt I might collapse at any moment…Several of my toes commenced to blacken and fester near the tips and the nails worked loose. There appeared to be little hope…It was easy to sleep on in the bag, and the weather was cruel outside…”

Assuming the Aurora had already left, and believing he was doomed, Mawson continued on with the thin hope that he would reach a place where he could leave his and Mertz’ diaries, so that others would learn their fate.

Assuming the Aurora had already left, and believing he was doomed, Mawson continued on with the thin hope that he would reach a place where he could leave his and Mertz’ diaries, so that others would learn their fate.

Yet, hope sprung anew on January 29, 1913 when Mawson discovered a cloth-covered stash of food with a note from members of his party who had been searching for his little group, left only hours before. Beyond the food, the note stated that the Aurora was still waiting for him.

Only 28 miles from Camp Denison at this point, it still took him 10 days to reach the base, partially due to his still weakened state, despite the extra supplies, but also due to a blizzard that kept him stranded in a cave for nearly a week just a few miles from the main camp. When he did emerge from the cave and make the final push to the waiting ship, the sight he saw was the Aurora off in the distance, sailing away… He had missed it by only a matter of hours.

But this was not the end. Six of his colleagues had volunteered to remain behind to search for the missing party. Upon Mawson’s arrival, the small group attempted to call the Aurora back via a wireless telegraph but due to the ever worsening weather, the ship could not return nor remain and so sailed home.

Forced to spend another winter on the frozen continent, the well provisioned group made good use of their time, performing additional scientific research, including studying the Aurora Australis (see: What Causes the Northern and Southern Lights), mapping the region further, and discovering the first meteorites in Antarctica, among other things. Through it all they were able to communicate with the outside world via experimenting with long-range wireless transmissions.

Forced to spend another winter on the frozen continent, the well provisioned group made good use of their time, performing additional scientific research, including studying the Aurora Australis (see: What Causes the Northern and Southern Lights), mapping the region further, and discovering the first meteorites in Antarctica, among other things. Through it all they were able to communicate with the outside world via experimenting with long-range wireless transmissions.

Despite the work and now plentiful supplies, it took Mawson some time to mentally recover from his ordeal. He stated, “I find my nerves in a very serious state, and from the feeling I have in the base of my head I have suspicion that I may go off my rocker very soon. My nerves have evidently had a very great shock.”

Mawson returned to Australia in February of 1914. For his work exploring Antarctica, he received the Founder’s Gold Medal in 1915 and the David Lingstone Centenary Medal in 1916. He also wrote a fascinating account of his ordeal in 1915, The Home of the Blizzard. (A more recent account of Mawson’s expedition was published in 2013 by David Roberts: Alone on the Ice: The Greatest Survival Story in the History of Exploration.)

He married and was knighted in 1914, served as a Major in the British Army during World War I, became a professor at the University of Adelaide, and even returned to Antarctica in 1929-31. He died from a stroke on October 14, 1958 at the age of 76. Today, his visage can be found on the Australian one hundred dollar banknote.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- To Boldly Go Where No One Has Gone Before

- A 17 Year Old Girl Survived a 2 Mile Fall Without a Parachute, then Trekked Alone 10 Days Through the Peruvian Rainforest

- The Tale of the Man Who Nearly Drowned While Falling from the Sky

- Why Penguins’ Feet Don’t Freeze

- The Man on the Raft: The Story of Poon Lim

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

“David Livingstone Centenary Medal”, not “David Lingstone Centenary Medal”.