The Archives of Terror

On December 22, 1992, former school teacher Martin Almada discovered thousands of documents that detailed the systematic repression of Paraguayans under the government of dictator General Alfredo Stroessner. Almada stumbled upon what has come to be known as Paraguay’s Archives of Terror in the basement of a police station in the capital city of Asuncion while working with a judge, José Fernández, to find the police records to Almada’s own four-year ordeal as a political prisoner. Approximately four to five tons of paperwork—a total of 700,000 papers and microfilm pages—filled the room from floor to ceiling. Not only did they describe in graphic detail the kidnapping, interrogation, and imprisonment of political prisoners, but they also finally provided hard proof of Operation Condor.

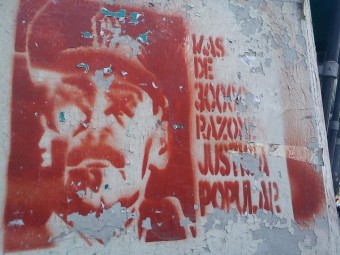

Operation Condor took place approximately between the mid-1970s to the early 1980s. The military governments of Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay conspired to thwart the plans of men and women that they considered to be subversive elements within their borders. (The operation was initially supposed to be about removing communist influence, but quickly became a tool to remove anyone the governing bodies deemed subversive for whatever reason.) Operation Condor created an agreement where each of the member countries could pursue any person or persons that they believed to be subversive into another of the member countries without fear of causing an international incident. In fact, the countries worked together to detain, torture, or even kill, subversives who crossed over their borders.

Using the broad term “subversive” in Operation Condor allowed the dictators to apply the term to more than just guerrilla fighters or communists. That meant anyone who questioned the status-quo or offered even the slightest opposition to the regime. Members of the media, former and current legislators, union representatives, and even teachers could be arrested or kidnapped. Those men and women then faced interrogation, torture, confinement, and even the possibility of death, sometimes via “death flights,” where the condemned were simply flown out to sea and tossed alive out of the plane or helicopter to plunge down into the ocean. Needless to say, a number of these individuals disappeared without a trace, though there are known instances of some of the bodies washing up on shore.

Martin Almada, the man who discovered the Archives of Terror, experienced Operation Condor firsthand. He was working as an elementary school principal in Paraguay when the military took him from his home in November of 1974. After being seen by a military tribunal with representatives from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, and Paraguay and being accused of working as an intellectual terrorist, Almada was tortured.

They tortured me for 30 days….For the first 10 days, they would call my wife and make her listen to me cry, to hear my screams as I pleaded for help. On the ninth day, they sent her my blood-soaked clothes, as was customary in those days. It was customary to first pull off the nails, then cut of an ear, then cut out the tongue; they just kept cutting.

Almada, who was president of an education association that vocally opposed the ruling dictatorship at the time, committed the “crimes” of instituting a liberation education in his school, helping to build houses for poor teachers, and defending a PhD dissertation that claimed the education system in Paraguay only benefited the upper class. In short, his actions showed where and how Stroessner’s regime was failing and he wasn’t keeping silent about it.

Operation Condor took place within the larger conflict of the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. (See: How Did the Cold War Start and End) The United States had an interest in keeping communism out of the Western Hemisphere, so they cultivated relationships among the dictators and military regimes holding power in South America, with some evidence that it was the CIA that helped setup specialized telecommunications systems between the governments, among other types of support, to help facilitate the removal of communist “subversives” in these nations.

As U.S. General Robert W. Porter stated in 1968, a few years before Operation Condor got underway, “in order to facilitate the coordinated employment of internal security forces within and among Latin American countries, we are…endeavoring to foster inter-service and regional cooperation by assisting in the organization of integrated command and control centers; the establishment of common operating procedures; and the conduct of joint and combined training exercises.”

Beyond this, political science professor and author of Predatory States, which detailed the United States’ involvement in Operation Condor, J. Patrice McSherry, noted there is “increasingly weighty evidence suggesting that U.S. military and intelligence officials supported and collaborated with Condor as a secret partner or sponsor.”

A recently declassified document from the U.S. Department of State, known as the Shlaudeman Memorandum, also shows that the United States understood the governments’ positions, noting that, “This siege mentality shading into paranoia is perhaps the natural result of the convulsions of recent years in which the societies of Chile, Uruguay and Argentina have been badly shaken by assault from the extreme left…”

They also noted that, “The problem begins with the definition of ‘subversion’ — never the most precise of terms. One reporter writes that subversion ‘has grown to include nearly anyone who opposes government policy.’ In countries where everyone knows that subversives can wind up dead or tortured, educated people have an understandable concern about the boundaries of dissent.”

The Shlaudeman Memorandum also mentions rumors that Argentina’s police murdered Uruguayan refugees as a favor to Uruguay, though it isn’t known how much merit there is to these accusations.

Today, the Archives of Terror give ample and well documented proof of the atrocities to survivors, their families, and the families of the missing. Such evidence played heavily in the plaintiffs’ favor when a group of former political prisoners decided to sue police officials whom they claimed tortured them during interrogations. The defendants’ initial response of having no idea who the plaintiffs were crumbled when the Archives were discovered and the transcripts of the interrogations contained the names of every plaintiff present.

All in all, Operation Condor is thought to have resulted in something on the order of 300,000-500,000 people arrested and imprisoned, about 30,000 people having disappeared (some perhaps killed, while others secretly fled to other nations), and an estimated 50,000-60,000 or so people killed.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The American Government Once Intentionally Poisoned Certain Alcohol Supplies, Resulting in the Death of Over 10,000 American Citizens

- The Largely Forgotten Paris Massacre of 1961

- One of the Most Shocking CIA Programs of All Time: Project MKUltra

- When the Canadian Government Used “Gay Detectors” to Try to Get Rid of Homosexual Government Employees

- The Story Behind the Man Who was Killed in the Famous “Saigon Execution” Photo

- Files in Paraguay Detail Atrocities of U.S. Allies

- Truth Commission: Paraguay

- UN urged to save vital archives of Pinochet’s terror

- Exposing the Legacy of Operation Condor

- Operation Condor: Setting precedent from one ‘war on terrorism’ to the next

- Shlaudeman Memorandum

- Condor legacy haunts South America

- How Paraguay’s ‘Archive of Terror’ put Operation Condor in focus

- Paraguay’s archive of terror

- Rights-Paraguay: New ‘Archives of Terror’ Unearthed

- Paraguay’s Dark Side: Interview with Martin Almada, Former Political Prisoner

- The Cold War (1945-1963)

- Image Source

| Share the Knowledge! |

|