Scamming Pan Am

Being an early adopter can be a risky proposition, especially for a large company. On the one hand, no company wants to fall behind as its competitors take full advantage of a new game-changing technology. On the other hand, many seemingly revolutionary developments ultimately turn out to be nothing but overhyped fads, leaving early adopters saddled with expensive white elephants. This was the dilemma facing America’s airlines and aircraft manufacturers in the early 1950s as they debated whether to embrace the futuristic new technology of jet propulsion. While jets promised unheard of speed, passenger comfort, and reliability, there were many reasons to be skeptical. For one thing, aircraft manufacturers were still equipped up to produce the same propeller-powered aircraft they had built during WWII and were reluctant to retool their factories. Jets also required longer runways, new airports, and new air traffic control systems to handle them, and the technology was so unproven that the development costs for a jet airliner were likely to be enormous. All these factors created a chicken-and-the-egg problem whereby no manufacturer was willing to invest in jets unless enough airlines would buy them – and vice-versa. And worse still, the jet age had already suffered its own tragic false start.

Being an early adopter can be a risky proposition, especially for a large company. On the one hand, no company wants to fall behind as its competitors take full advantage of a new game-changing technology. On the other hand, many seemingly revolutionary developments ultimately turn out to be nothing but overhyped fads, leaving early adopters saddled with expensive white elephants. This was the dilemma facing America’s airlines and aircraft manufacturers in the early 1950s as they debated whether to embrace the futuristic new technology of jet propulsion. While jets promised unheard of speed, passenger comfort, and reliability, there were many reasons to be skeptical. For one thing, aircraft manufacturers were still equipped up to produce the same propeller-powered aircraft they had built during WWII and were reluctant to retool their factories. Jets also required longer runways, new airports, and new air traffic control systems to handle them, and the technology was so unproven that the development costs for a jet airliner were likely to be enormous. All these factors created a chicken-and-the-egg problem whereby no manufacturer was willing to invest in jets unless enough airlines would buy them – and vice-versa. And worse still, the jet age had already suffered its own tragic false start.

On May 2, 1952, the world’s first jet airliner, a De Havilland DH106 Comet, made its inaugural commercial flight from London to Johannesburg. It was an event that stunned the world; American manufacturers had nothing to compete with the Comet, and it seemed as though Britain – and not America – would rule the post-war skies. But the Comet’s reign was tragically short-lived. On January 10, 1954, a BOAC Comet departing from Rome broke up in mid-air over the Mediterranean, while three months later on April 8, a South African Airways Comet crashed near Naples. These disasters led to the entire Comet fleet being grounded until the cause of the crashes could be determined. A lengthy investigation eventually concluded that the crashes were due to metal fatigue caused by the Comet’s square windows, whose corners caused stress to build up in the aircraft’s skin every time the cabin was pressurized. While the Comet was redesigned with round windows and returned to service in 1958, it was already too late: Britain had lost its early lead in the jetliner field, largely thanks to one man: Juan Trippe.

Trippe, the legendary founder and CEO of Pan American Airways, was known for being the first to jump on any new development in aviation technology, forcing all his competitors to play follow-the-leader. So it was that shortly after the Comet’s first flight, Trippe placed an order for three for Pan Am. While Trippe was criticized for ordering a foreign aircraft, there was method to his madness, for Trippe knew that this move would goad American manufacturers into developing their own jets. His instincts paid off, and in 1954 Seattle manufacturer Boeing unveiled its model 707, America’s first jet airliner. In response, Douglas Aircraft, which had stubbornly continued to produce propeller airliners, was forced to release their own competitor, the DC-8. While it may seem that Douglas was late to the party, they actually managed to use this late start to their advantage. Figuring that after spending nearly $15 million on development Boeing would be unwilling to make any major changes to its new aircraft, Douglas took the opportunity to improve upon the major shortcomings of the 707 design, such as its short range and small passenger capacity. The 707 might have been the first, but it would not be the best.

The gamble paid off, and on October 13, 1955, Pan Am placed an order for 25 DC-8s. It was a staggering turn of events, given that at this point the DC-8 only existed on paper and as wooden mockups while the 707 prototype had been flying for over a year. As more and more airlines jumped on the bandwagon and ordered DC-8s, Boeing was forced to bite the bullet and produce a larger, longer-range version of the 707 called the Intercontinental. Turning the tables again on Douglas, Boeing secured the sale of 17 Intercontinental 707s to Pan Am and quickly began raking in orders from other carriers. By shrewdly playing America’s aircraft manufacturers off one another, Juan Trippe had dragged the industry kicking and screaming into the jet age – and on Pan Am’s own terms.

But Juan Trippe was not the only master of the freewheeling antics that characterized the early jet age, and he himself would soon fall for one of the most inspired ploys in civil aviation history. Enter the mastermind behind National Airlines, George Baker.

The American airline industry in the 1950s was very different from today, with international travel being dominated by giants Pan Am and TWA while domestic routes were divided among by dozens of small regional airliners who fought fiercely for territorial dominance. Among these were rivals National Airlines, headed by George Baker, and Eastern Airlines, headed by WWI flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker. In 1958 both airlines were competing for control of the lucrative New York-to-Miami route and keen to get their hands on the new jet airliners before the other. But Boeing and Douglas were full-up with orders from the big airlines, and it would be years before any aircraft became available for the smaller operators. Desperate to get a leg up on Eastern, George Baker turned to possibly the one man he hated more than Eddie Rickenbacker: Pan Am’s Juan Trippe.

Baker knew that Pan Am suffered a slump in ticket sales every winter – the same period when National did its best business. He thus proposed leasing two of Pan Am’s new Boeing 707s for the 1958-1959 winter season. And to make the deal even more enticing, he made Juan Trippe an offer he couldn’t refuse, offering him 400,000 shares in National stock with an option for another 250,000. On hearing this offer Trippe’s jaw must have hit the floor, for exercising that option would have given Pan Am a controlling interest in National Airlines. For years Trippe had wanted to establish domestic U.S. routes, but the U.S. Government, wary that Pan Am would use its political clout to monopolize the domestic market, had stood in his way. Now, out of the blue, his dream was seemingly being handed to him on a silver platter. It seemed too good to be true, but Trippe nonetheless accepted Baker’s offer and handed over the planes.

Trading controlling interest in one’s company for a temporary advantage over a rival might seem about the most idiotic thing a CEO can do, but George Baker was no fool. He was counting on the intervention of a certain Government body, the Civil Aeronautics Board, to swing the deal entirely in his favour. From 1939 until 1985, the CAB regulated all aspects of civil aviation within the United States, and was responsible for barring Pan Am from flying domestic routes. Baker knew that the CAB would likely block National’s deal with Pan Am, but gambled on the fact that such a large, slow-moving Government bureaucracy would take months to do so – giving National just enough time to beat Eastern in the race for jets and fly the New York-Miami route all winter.

Amazingly, everything worked out exactly as Baker had planned it: the CAB blocked the deal, Baker got to pull a fast one on Pan Am, and National Airlines gained the distinction of being the first American airline to fly jets on domestic route – beating its rival Eastern Airlines by two years.

But as is often the case with business, nothing lasts forever, and though National enjoyed great success in the next decades – even expanding internationally in the 1970s – following a series of takeover attempts by Texas International Airlines and old rival Eastern Airlines, in 1980 National was finally acquired by Pan Am, at last giving the airline giant the domestic routes it had been seeking for nearly five decades. However, it’s hard to tell who had the last laugh, as the acquisition of Eastern proved to be a disaster for Pan Am, contributing to its ultimate demise in 1991. That year also saw the collapse of Eastern Airlines, which despite soldiering on for 65 years was finally done in by a combination of high oil prices, competition due to airline deregulation, and labour unrest. Just like that, three of the pioneers of American civil aviation had suddenly ceased to exist. Yet despite these ignoble ends, it cannot be forgotten that it was these airlines and others like them that gave us the world of safe, reliable, and affordable jet travel we enjoy today, and it is hard not to admire the sheer wiliness, creativity, and chutzpah it took to get us there.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Has Any Passenger Ever Landed a Commercial Airliner Like You See in Movies?

- How Commercial Airplanes Keep a Steady Supply of Fresh Air and How the Emergency Oxygen Masks Supply Oxygen Given They are Not Hooked Up to Any Air Tank

- The Pass That Allows People to Fly Free Forever and the Airline’s Attempt to Kill It

- What is the Best Way to Survive Falling Out of a Plane with No Parachute?

Bonus Facts

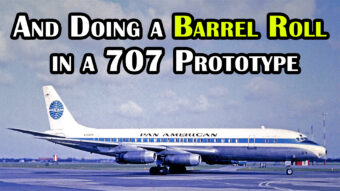

#1: On August 5, 1955, Boeing held a demonstration flight of the Dash-80, the prototype for the 707 jetliner, over Lake Washington just outside Seattle. At the controls was legendary test pilot Alvin M. “Tex” Johnston, who was determined to give the spectators below a show they would never forget. As the assembled delegation of airline representatives looked on in amazement, Johnston pulled the 42-ton jetliner, 49-meter wingspan and all, into a full barrel roll. Furious, then-head of Boeing, Bill Allen, called Johnston to his office and angrily asked him just what he thought he was doing. According to legend, Johnston simply replied: “I was selling airplanes.”

#2: While the De Havilland Comet was the first jet airliner to fly, Britain was very nearly beaten to the punch by an unlikely competitor: Canada. On August 10, 1949 – only 13 days after the Comet – the prototype C102 Jetliner, designed and built by A.V. Roe Canada Limited, took to the skies for the first time above Malton Airport in Ontario. While the Jetliner was smaller and had a shorter range than the Comet, it was designed not for international travel but shorter domestic routes such as between Toronto, Montreal, and New York, which it could fly 20% more cheaply than competing propeller-driven airliners. In April 1950 the Jetliner became the first jet to carry mail between Toronto and New York, a trip it completed in only 58 minutes – half the previous record. So momentous was this achievement that the crew was treated to a ticker-tape parade in Manhattan, and Avro was certain that the orders would start pouring in.

Unfortunately, the Jetliner appeared doomed from the start. Following a change of management, in 1947 Trans Canada Airlines, who had originally contracted Avro to build the Jetliner, changed its mind and pulled out of the agreement. This left Avro without a buyer, and the prototype Jetliner was only completed thanks to a cash injection from the Canadian Government. But it would be this same Government who would finally seal the Jetliner’s fate. In the early 1950s Avro was engaged in building CF-100 Canuck all-weather interceptors for the Royal Canadian Air Force, and the Government came to see the Jetliner as an unnecessary distraction from this strategically vital task. So, in December 1951, Avro received a shocking order from Minister of Supply C.D. Howe: scrap the Jetliner.

Desperate to save their advanced new aircraft, Avro turned to an unusual ally: eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes. On April 7, 1952, a delegation from Avro flew the Jetliner to Hughes’ facility in Culver City in California. Over the next week Hughes flew the aircraft several times and stayed up late with the Avro engineers poring over the blueprints. By the end of the week, Hughes was fully converted and agreed to buy 30 Jetliners for his airline, TWA. He even made an agreement with American aircraft manufacturer Convair to produce the Jetliner under license, freeing up Avro’s production capacity. Deal in hand, Avro’s executives returned to Canada and pleaded the Government for a few months to hammer out the details. But it was not to be. The Government held firm on its order, and on December 13, 1956, the only flying Jetliner and its half-completed sister were cut up for scrap. All that remains of the Jetliner today is the cockpit section, stored at the National Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa – a sad reminder of a time when Canada almost ruled the skies.

Expand for References| Share the Knowledge! |

|