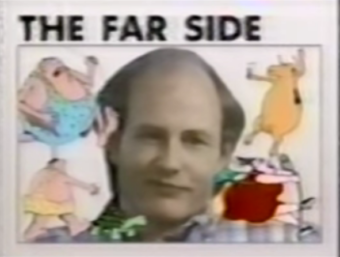

On The Far Side

For 15 years, Gary Larson took millions of readers over to the “Far Side.” Using anamorphic animals, chubby teenagers, universal emotions, a simple drawing style and a really bizarre, morbid sense of humor, The Far Side became one of the most successful – and praised – comic strips of all time. But like many cartoonists, Larson has remained rather elusive. In 1995 (about 11 months before the creator of Calvin and Hobbes did the same), he abruptly ended the comic strip – perhaps even a bit prematurely according to many of his fans. So, how did Larson get to the “Far Side?” And what was with his fascination with making aliens look stupid?

For 15 years, Gary Larson took millions of readers over to the “Far Side.” Using anamorphic animals, chubby teenagers, universal emotions, a simple drawing style and a really bizarre, morbid sense of humor, The Far Side became one of the most successful – and praised – comic strips of all time. But like many cartoonists, Larson has remained rather elusive. In 1995 (about 11 months before the creator of Calvin and Hobbes did the same), he abruptly ended the comic strip – perhaps even a bit prematurely according to many of his fans. So, how did Larson get to the “Far Side?” And what was with his fascination with making aliens look stupid?

Larson was born in 1950 – in the midst of the baby boomer generation – in a blue-collar neighborhood of Tacoma, Washington. His father was a car mechanic, someone who didn’t mind getting a bit dirty, which was a trait he passed on to his two sons. Larson has often reminisced about how he and his brother would wade in the nearby Puget Sound looking for critters like octopi and salamanders, several of which would end up in his later comics.

As he explained to the New York Times in 1998, this love of wildlife has continued throughout his life. He originally was even a biology major at Washington State University before deciding that he wasn’t into all that schooling. “I didn’t want to go to school for more than four years, and I didn’t know what you did with a bachelor’s in biology,” Larson told the Times, ”so I switched over and got my degree in communications. I regret it now. It was one of the most idiotic things I ever did.”

Throughout his adult life, he was a keeper of exotic pets including tarantulas, African bullfrogs, Bermuda pythons, Mexican king snakes, and carnivorous South American ornate horned frogs. Also, through high school and college, he got really into jazz, both listening and playing. And he was pretty talented, especially on the guitar and banjo.

All of this is to say that being a cartoonist was not originally part of Larson’s career plan- he was never even terribly good at drawing. Unlike many cartoonists of his era, Larson says that he more or less fell into it.

In the mid-1970s, his jazz career was slowing getting better and better until he was passed over for a gig he thought he was going to get with an established band. Upset, loathing his job at a music store (establishments which are, as he put it, “graveyards of musicians”), and in need of money, Larson began to draw animals, poorly.

While at the aforementioned day job at a music shop in 1976, he drew one-panel cartoons featuring animals making pithy, weird jokes. Then, Larson sent them into local Seattle magazine Pacific Search and, much to his surprise, they purchased six of them for $90 (about $400 today).

He thought this was the easiest money he had ever made, so he kept doing it. Soon after, a small weekly Tacoma publication called the Sumner News Review purchased his cartoons – which he had now named Nature’s Way due to the fact that it was mostly about animals – for $3 a pop.

Looking at Nature’s Way today, one can spot many similarities to Far Side (which was still a few years away). The comic humanized animals, making them talk, banter, and act like we do. As for the humans, they were often chubby, goofy-looking and not particularly bright. In other words, it seems rather clear that Larson has always held animals in a higher regard than his fellow humans.

After a brief hiatus from publication, around 1978 or 1979, the Seattle Times gave Nature’s Way a weekly space next to the “Junior Jumble” puzzle, with Larson now earning five times as much per week- a whopping $15 per comic (about $50 today).

While a paid cartoonist, $15 per week isn’t enough to live off of so Larson went to work as an animal cruelty investigator for the Seattle Humane Society. According to a story he told Salon, on the way to the interview for the job, Larson accidentally hit a dog with his car…

To him, that was signal that perhaps this line of work wasn’t meant to be for him. (He also said that the dog ended up being okay.) So, on the side, he kept making his comics.

Trying to gain a second revenue stream, he drove to San Francisco in an attempt to sell Nature’s Way to the San Francisco Chronicle. Admittedly, it was a stab in the dark. He sat for hours in the reception area and later called in twice a day to see if anyone had looked over his work. The most he got in response at this stage was a bit of sympathy from the receptionist.

It was set-up to be a disappointment, but much to his astonishment, when the paper did finally get back to him, it turned out the editors not only loved his comic, but instead of running it weekly, they wanted it daily. On top of that, they weren’t just going to run it in one newspaper, but were going to syndicate it to start across 30 newspapers! Their only request was that Larson switch the name from Nature’s Way to one they had come up with- The Far Side.

As to that name change, Larson stated, “They could have called it Revenge of the Zucchini People for all I cared.” The point was that between the switch to daily and being syndicated, he could now make a living doing the comic full time.

This was a fortunate turn of events as that very same week the Seattle Times sent him a letter noting they were canceling Nature’s Way citing that they were getting too many complaints that the comic was weird and offensive.

If he hadn’t just gotten the deal with Chronicle, he later told Rolling Stone Magazine, that “I’m certain I would have bagged it all.”

As noted, the San Francisco Chronicle put the comic in 30 newspapers nearly immediately and quickly audiences took to the weird, morbid humor. Well, at least, some did. Through the comic’s decade and a half run, newspapers across the country got an assortment of complaint letters about the comic, mostly with people stating that they found the cartoon disturbing or offensive. Some said that Larson needed “psychotherapy” while others just wanted their “Annie” back.

In the early days, the San Francisco Chronicle editors, unlike the Seattle Times‘, simply didn’t care. They thought the comic was the work of genius.

But as for the steady stream of complaints, this always took Larson by surprise with him telling the Associated Press in 2003, “You start off thinking that everyone in the world has the same sense of humor as your six friends. I was surprised at just how upset some people could be.”

Among the massive fan base that The Far Side would eventually develop, interestingly scientists and academics were among the first to take to the comic, despite Larson’s frequent jabs at this very same group. For example, perhaps the most famous Far Side comic shows an image of a chubby boy with glasses and holding books attempting to enter the “Midvale School for the Gifted.” He’s trying to push the door open while it’s clearly marked pull. Or the one where a group of scientists are trying to figure out an equation only to be interrupted by the ice cream truck. Or this classic where the scientist realizes the glass he’s holding is lemonade and not a culture of amoebic dysentery. Next to him another scientist is casually sipping a glass of what he thinks is lemonade.

The strip also had a tangible impact on the world of paleontology. In an 1982 comic, a group of cavemen are in lecture hall being shown a slide of a dinosaur. The caveman instructor is pointing to the spiky tail of a Stegosaurus while saying, “Now this end is called the thagomizer…after the late Thag Simmons.” As it turned out, in real life, no one had actually given that part of the Stegosaurus’ tail a name. Despite Larson’s fudging of the facts (in actuality, dinosaurs and humans missed each other by more than 140 million years), paleontologists adopted “thagomizer” as the official name of the spikes on a Stegosaurus.

A decade and a half and over 4,000 comics later, with a new premise for each cartoon (as opposed to normal comic strips, which could extend a premise for weeks and use repeating characters to further simplify things) and Larson was burnt out. In 1994, he announced his retirement citing that he wanted to avoid “the Graveyard of Mediocre Cartoons.” The final strip was published on January 1, 1995 and it was different than any other Far Side. It was two panels.

At the peak of his comic’s run, it appeared in over 2,000 newspapers and, all told, Larson has sold over 50 million Far Side books; that’s not to mention the annual desk calendar version that Larson describes as tantamount to “printing money” every year.

Today, Larson lives a quiet life in Washington state, constantly maintaining that he wants to remain out of the spotlight. Among a few other projects, he’s gone back to jazz and can be sometimes seen performing in clubs with his band, and even the occasional wedding. While it’s been more than two decades since Larson retired from drawing cows, snakes, and chubby kids, the comic still resonates. Where else could you find out the real reason dinosaurs went extinct?

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Why Superheroes Wear Their Underwear on the Outside

- What Ever Happened to the Creator of Calvin and Hobbes?

- WWII and the Creator of Captain America

- The Story of How SpongeBob SquarePants Made It to Air

- The Soviet Superman: Red Son

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

“Anamorphic animals”? “Bermuda Pythons”? I could go on and on, but suffice it to say, this website needs a proofreader at the very least.

Sheesh.