The London Garrotting Panic of the Mid-19th Century

Although crime in England’s capital was on the decline in the mid-19th century, thanks in part to the relatively recent formation of the London Metropolitan Police Force in 1839, fear of crime was a persistent, reoccurring issue thanks to a few instances of robbery and murder, and, of course, the news media. In particular, the so-called “garrotting” cases, where someone strangles someone else, often using their arm or a length of wire, cord, or cloth, seemed to touch the rawest nerve with the people of London, with the fear of garrotting reaching a fever-pitch in the 1860s.

Although crime in England’s capital was on the decline in the mid-19th century, thanks in part to the relatively recent formation of the London Metropolitan Police Force in 1839, fear of crime was a persistent, reoccurring issue thanks to a few instances of robbery and murder, and, of course, the news media. In particular, the so-called “garrotting” cases, where someone strangles someone else, often using their arm or a length of wire, cord, or cloth, seemed to touch the rawest nerve with the people of London, with the fear of garrotting reaching a fever-pitch in the 1860s.

Exactly when enterprising ruffians first realised that they could increase their odds of successfully robbing a person dramatically by placing that person in a chokehold first isn’t clear, since many crimes back in those days often went unreported due to a general mistrust of the police amongst poorer folk. However, historic letters written by purported survivors of garrotting sent to various London newspapers date back to at least 1850. A popular theory is that the practise was first thought up by criminals on convict ships, where guards would often use roughly applied chokeholds to quickly knock out an aggressive criminal, hopefully without causing any long lasting injuries. It’s believed that this coldly efficient method of putting someone down was picked up by criminals who inevitably began using it in their day-to-day criminal dealings.

The weird thing about garrotting and how widely it was reported at the time is that it doesn’t actually appear to have been all that common; even during the supposed height of the “garrotting panic of 1862”. So why the panic? As it turns out, although garrotting itself was never a major problem in London, newspapers from the era positively loved reporting on it. This led to the few isolated cases that did happen being blown way out of proportion and reported on to such an extent that the people of London were led to believe the streets were filled to the brim with roving rabbles of ruffians armed with lengths of wire.

Newspapers’ coverage of garrotting exploded in 1862 when an MP called Hugh Pilkington was strangled and robbed of his watch on his way home from the House of Commons. Pilkington survived, but news of the incident was widely reported on to such an extent that Parliament pushed through the Security from Violence Act in 1863. Under the terms of this new act of Parliament, criminals convicted of any violent theft could be punished with “up to 50 lashes” along with a hefty prison sentence.

Following the attack, the police similarly became noticeably more heavy-handed, presumably in an attempt to reassure the public that they were “doing something” about the problem. London’s streets were flooded with plain clothes police officers; minor crimes, like pickpocketing, that had previously been punished with a small fine, suddenly became issues for the courts.

In an effort to prove that they were stomping down on garrotting in particular, the police also began classifying regular robberies and even drunken brawls as instances of garrotting, to fudge their numbers. This is similar to how in the 1930s they would often list instances of theft as “lost property” to make it appear as though those crimes didn’t happen as often as they actually did.

By far the most ridiculous by-product of the panic were the devices invented to dissuaded potential garrotters. Various designs of hulking neck-collars with large spikes were patented. A cravat with a blade sewn into the hem (meant to either cut the attacker’s arm or the device he was using to strangle you) was also a thing.

But perhaps the greatest example of the extreme lengths people went to back then to protect themselves from garrotting was invented by gun maker Henry Ball and patented in 1858- the “Anti-Garrotter Belt Pistol”. This belt-gun was designed to be worn on the rear. If someone was trying to strangle you from behind, you’d discharge the weapon into said attacker’s sensitive mid-section. This not only was a working device, but is now considered “among the rarest of firearms curiosa” with only a handful of specimens known to exist today. Beyond potentially taking away the ability of your attacker to have children, it no doubt also left the person firing it with a nice sized bruise and subsequent lower back pain.

Although the press continued to discuss garrotting all throughout the 1860s, actual verifiable reports of the crime dried up in 1863 right after a large amount of arrests were made in response to the passing of the previously mentioned Security from Violence Act.

Although the press continued to discuss garrotting all throughout the 1860s, actual verifiable reports of the crime dried up in 1863 right after a large amount of arrests were made in response to the passing of the previously mentioned Security from Violence Act.

As they do so often when a story reaches its saturation point, eventually the newspapers kind of forgot about garrotting and started reporting on other types of crimes, which unfortunately for their sales-rates didn’t cause the same type of public panic… That is until a few murders in a small region of London’s East End sent the nation into yet another panic when Jack the Ripper began his reign of terror in 1888. But that’s a story for another day.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Mock Execution of Fyodor Dostoevsky

- Toads Around Your Neck and Forcing Kids to Smoke- Escaping The Great Plague of London (1665-1666)

- The Greatest Practical Joke of the 19th Century, the Berners Street Hoax

- The Difference Between The UK, England, And Great Britain

- Hobbs and His Lock Picks: The Great Lock Controversy of 1851

Bonus Facts:

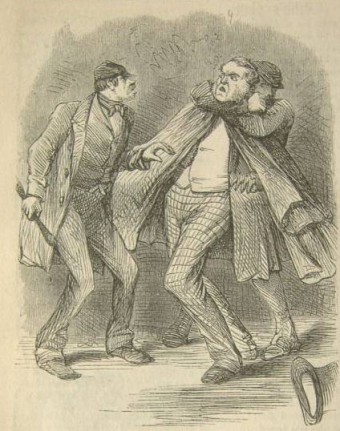

- As an example of how paranoid some members of the public were about being garrotted. In one particularly humorous case, two men in London attacked each other in self defence while walking home along the same road. After the fight, both men tried to insist to the police that they thought they were about to be the victim of a garrotting attack.

- During the height of the panic, you could hire a really tall or burly man to walk you home to scare away criminals. A pair of brothers even went as far as taking out an ad which read as follows: “THE BAYSWATER BROTHERS (whose height is respectively 6 feet 4 inches and 6 feet 11, and the united breadth of whose shoulders extends to as much as 3 yards, 1 foot, 5 inches) give, respectfully, notice to the Gentry and Public of Paddington, Kensington, Stoke Newington, Chelsea, Eaton Square, and Shepherd’s Bush, that they will be most happy, upon all social and jovial expeditions, such as dinner and evening parties, as well as tee-total meetings, to escort elderly or nervous persons in the streets after dark, and to wait for them during their pleasure, so as to be able to escort them home again in safety. No suburb, however dangerous, objected to. and the worst garrotting districts well known, as the Brothers, both BILL and JIM, were for several months in the Police Force. – Terms, so much a head per hour, according to the person’s walk of life. A considerable reduction on taking a party of twelve or more. Distance no object. Testimonials, and ample security given.”

- Spain used garroting as a method of execution up until 1974 when they executed Salvador Puig Antich and Heinz Chez in this way. Others were later sentenced to death by garroting, but ultimately the death penalty was abolished in Spain in 1978.

- The guillotine became popular during the French revolution as the people’s “avenger” against their tyrants, though first used on the 25th of April, 1792 to execute a common thief- Nicolas Pelletier. It continued to be used as France’s main method of judicial execution until the abolition of capital punishment in France in 1981. The last person executed via the guillotine in France was a Tunisian immigrant named Hamida Djandoubi, on the 10th of September, 1977. Djandoubi was convicted for torturing and murdering his 21-year-old ex-girlfriend, Elisabeth Bousquet, in Marseille.

- Want to Become a Sharp Dresser? Sport a Knife in Your Collar

- Crime and the Victorians

- London’s Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City

- Crime in England 1815-1880: Experiencing the Criminal Justice System

- Victorian London – Crime – Violence and assault – garrotting / mugging

- Stranglehold on Victorian Society

- Punishments at the Old Bailey

- The Anti-Garrotters Pistol

- Capital Punishment in Spain

- Garrote

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

It makes a person wonder why we have ever trusted what is printed in a newspaper? Or, in the here and now, any reporting called “news”? This “Garrotting Panic” scenario is still their formula 150 years later.

Typo in paragraph 8: “it now doubt also left the person” should be “it no doubt also left the person”

Brilliant article! Is there a theory that we can draw from when the media through moral panic make us purchase things, such as the anti garroting collar mentioned in this piece?