The Restoration Fabrication

Here’s the bizarre story of an anonymous artist so desperate to receive credit for his work that he took himself to court.

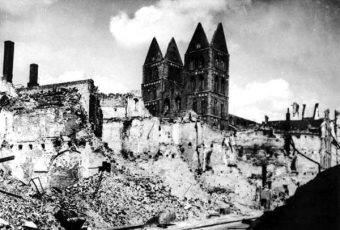

On March 28, 1942, the German port city of Lübeck was nearly obliterated by Allied bombers during World War II. More than 230 British planes dropped 400 tons of bombs, destroying thousands of homes, the town hall, the merchant district, and several churches dating back seven centuries, including the huge Gothic cathedral known as the Marienkirche (Church of Mary).

The bombing created a firestorm so hot that the church bells melted. After the raid ended and townspeople began to assess the damage, a remarkable discovery was made in the Marienkirche. The intense heat had also melted dozens of layers of paint off the walls. Underneath that paint: frescoes, a style of painting in which pigment is applied directly onto a wet plaster wall. The paintings of saints, biblical scenes, and religious icons dated back to the 1250s, when the church was built. After what was dubbed “the miracle of the Marienkirche,” the town quickly came together to erect a temporary roof for the cathedral to protect it from further attacks, so that the frescoes could be restored when the war was over…whenever that might be.

FEY TO GO

After the end of the war in 1945, the roof and walls of the Marienkirche were rebuilt, and the work was completed in 1948. Town officials then hired celebrated German art restorer Dietrich Fey to bring the church’s frescoes back to life. Fey had apprenticed under his father, Ernst Fey, a Berlin art historian who had worked on the recovery and restoration of frescoes in churches throughout Germany in the 1920s and 1930s. But it was the elder Fey who was the artist; the younger Fey’s skills were more on the business side, landing commissions and finding wealthy patrons.

After the end of the war in 1945, the roof and walls of the Marienkirche were rebuilt, and the work was completed in 1948. Town officials then hired celebrated German art restorer Dietrich Fey to bring the church’s frescoes back to life. Fey had apprenticed under his father, Ernst Fey, a Berlin art historian who had worked on the recovery and restoration of frescoes in churches throughout Germany in the 1920s and 1930s. But it was the elder Fey who was the artist; the younger Fey’s skills were more on the business side, landing commissions and finding wealthy patrons.

By 1936 the Feys had more work than they could handle, and they needed a skilled assistant. That’s when they were approached by Lothar Malskat. A recent graduate of the Art Academy of Konigsberg (now the Russian city of Kaliningrad), Malskat could paint in any number of classic styles. (His favorite style: 13th-century Gothic painting, like the frescoes of the Marienkirche.) Malskat had hoped to become an artist, but when he got to Berlin, the only painting work he could get was painting houses. He was homeless and sleeping on a park bench when he asked the Feys for a job.

BRICK HOUSE

Malskat’s first assignment: paint Dietrich Fey’s house. But Fey also brought Malskat into the restoration business, loaning books on ecclesiastical art (religious paintings), and training him as they worked. Malskat proved his talent in the 1937 restoration of St. Petri-Dom, a cathedral in the city of Schleswig with artworks dating to the 14th century. At first, he had to undo damage caused by the Feys. Then they had to scrape away the work of an earlier restorer, August Olbers. They scraped away so much paint from Olbers’s 1880s restoration that they—oops!—also scraped away almost all of the original artwork.

Malskat knew what to do. He whitewashed the brick, and then tinted it to look old by combining lime with various colors of paint. Once that dried, he painted freehand (and from memory) the paintings that had been accidentally removed. Finally, Malskat and Fey artificially aged the drawings through a process called zurückpatinieren—rubbing them with a brick. Church leaders were impressed by the final product, as was Alfred Stange, an art historian at the University of Bonn. He called the murals “the last, deepest, final word in German art.”

FAKE IT UNTIL YOU MAKE IT

World War II ended the business; Malskat was drafted into the Wehrmacht, and was discharged at the war’s end. Now unemployed, he moved to Hamburg. Once again, he was homeless, subsisting by selling pornographic drawings. Finally, in late 1945, he tracked down Fey and asked for his old job back.

Germany was in tatters after the war. It was occupied by foreign powers and divided into two—West Germany and East Germany. The economy was weak, and any available funds were used to rebuild infrastructure; restoring art was not a priority for postwar West Germany. So Fey put his business skills and Malskat’s painting skills to good use: they started counterfeiting famous paintings. Fey provided Malskat with canvases, paints, brushes, and other supplies, along with art books and a list of names. His instructions: paint the works of Rembrandt, Picasso, Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, Edvard Munch, Marc Chagall, Jean Renoir, Edgar Degas, and others that could be sold to private collectors as the real thing. From 1945 to 1948, Malskat painted an estimated 500 forgeries.

Demand was so high that Malskat had to turn the paintings around quickly; he claimed to have spent just a day re-creating a painting by Rembrandt, and an hour for a Picasso.

DUST IN THE WIND

Thanks to aggressive government programs (as well as the Marshall Plan), the West German economy stabilized by 1948, diminishing the black market economy that had made Fey and Malskat’s forgery ring possible. With that stability, the restoration of the Marienkirche could finally commence.

Having acquired 150,000 deutschemarks through fund-raising efforts, Lübeck officials contacted Dietrich Fey (his father had since died) to restore the frescoes. But the centuries—and the bombs—had left the paintings in almost as bad a state as the ones at St. Petri-Dom. Malskat reportedly climbed the scaffolding to assess the damage to some paintings and noticed that some of the art was barely there at all, and what was there “turned to dust when I blew on it.” Restoring those frescoes would be impossible…but Malskat was up to the challenge. He’d do what he did before: create new art that looked like the old art.

In fact, he utilized almost all of the techniques he’d used at St. Petri-Dom: He whitewashed the walls, tinted them with lime and pigment, and started painting. He used old photographs and art books as a guide… but added personal touches. He modeled Mary on his sister Freyda, painted a bearded king to look like Rasputin, gave a saint the face of Marlene Dietrich, and made monks look like the local townsfolk.

GERMAN REUNIFICATION

The restoration was completed in September 1951, just in time to celebrate the 700th anniversary of the construction of Marienkirche. A special ceremony was held, attended by West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer. As he stared up at 10-foot-tall paintings of Gothic saints, Adenauer proclaimed, “This is uplifting.” He went on to call them “a valuable treasure and a fabulous discovery.”

The Marienkirche was a sensation, uniting Germans still battered and embarrassed after World War II. The newly restored old paintings filled Germans with national pride. The acclaim came quickly. The government printed two million postage stamps detailing the frescoes. One art historian called the murals “the most important and extensive ever disclosed in Germany.” Even in the United States, Time called the frescoes “a major artistic find.” Over the next year, more than 100,000 tourists flocked to Lubeck to see Marienkirche, bringing much-needed tourism—and cash—to the town.

All of this infuriated Lothar Malskat.

COMPENSATION FRUSTRATION

Fey was the public face of the restoration project (and took all the credit), but Malskat had done most of the actual work. He’d spent three years in the Marienkirche, providing the concepts and labor needed to produce dozens of paintings, virtually by himself. Fey paid Malskat a weekly salary of 110 deutschemarks (the equivalent of about $328 today), and paid himself about eight times as much—not even factoring in the 150,000-deutschemark bonus he received from Chancellor Adenaur, or the prestigious art professorship he was given. Yet in all of his public speeches and interviews about the Marienkirche, Fey never thanked Malskat. He never even mentioned him.

More than money, Malskat wanted credit. After his work on the church, he no longer saw himself as an art restorer—he saw himself as a creator and a true artist. Toward the end of the restoration, he started to leave clues about his work on the project. Malskat left “LM” on paintings as he finished them, and even “all paintings in this church are by Lothar Malskat.” Fey reviewed Malskat’s work every few days and painted over these personal touches.

For a year after completing his work at the Marienkirche, Malskat simmered in private, which couldn’t have been easy, considering that he was still doing restoration work (and more forgery work) for Fey in Lubeck. Finally, on May 9, 1952, Malskat had had enough. He walked into the Lubeck police station and gave a statement, asserting that the famed Marienkirche murals were a fraud, and that he had forged them under the direction and cooperation of Dietrich Fey. His reason for confessing: He was tired of being treated unfairly by Fey and he wanted the world to know the truth, and by doing so, reveal himself as the brilliant artist behind the beloved works of art.

CAN’T GET ARRESTED IN THIS TOWN

Only problem: The paintings were so beloved that nobody believed Malskat. Lubeck police threw him out of the station. He went to the local newspaper. Officials there were dismissive too, writing that Malskat’s claims were “the lamentable case of a painter gone crazy.”

Nobody wanted to see Malskat’s proof—before and after photographs of the church—either. They didn’t want to see that in one fresco, photographs showed that Mary Magdalene had shoes before the restoration…and no longer did. Or that the fringes of some works were decorated with turkeys, a bird not introduced to Germany until the 1500s, making it unlikely for them to appear in genuine artwork from the 1200s. (When the German news media reported this fact, a prominent German historian tried to explain it away, claiming that Vikings had brought turkeys to Germany in the 1100s.) The city of Lubeck issued a statement saying that Malskat’s charges were “rumors and purely malicious gossip.”

I WILL SEE ME IN COURT

When the law won’t cooperate, what can a person do? Take the law into their own hands. After spending most of 1952 trying, unsuccessfully, to convince the country that he was the artist responsible for Marienkirche, Malskat hired a lawyer named Willi Flottrong. Malskat gave him a huge folder of photographs of his earlier forgeries, primarily his Picasso and Rembrandt fakes. He argued that this established a pattern of criminal behavior.

So, on October 7, 1952, with the artwork in hand, Malskat’s lawyer went into the Lubeck police station to file criminal charges against Fey…and Malskat. Official charges from a third party forced the police to investigate and even arrest the two men. Police searched (a very cooperative) Malskat’s home and found a total of 28 pieces of counterfeit art. Two days after his lawyer filed charges on his behalf, Malskat got what he wanted: He was arrested for forgery. (And so was Fey.)

A REMARKABLE DISCOVERY

While Malskat happily sat in jail, awaiting his day in court, police gathered evidence against him. Art experts from around Europe examined Marienkirche. It took them just two weeks to issue a report, which, not surprisingly, said that upon close inspection, the frescoes were not legitimate. “The 21 figures are not Gothic, but painted freehand,” the report stated.

Prosecutors spent 10 months in all amassing testimony, and as the investigation unfolded, it became clear that several officials at Marienkirche knew exactly what Fey and Malskat were doing, but looked the other way. To avoid prosecution, the church superintendent retired early, and his second-in-command abruptly moved behind the Iron Curtain into East Germany.

Malskat’s trial began on August 10, 1954. To accommodate the hundreds of spectators and reporters, it was moved from the Lubeck courthouse to a local dance hall. The first witness, as well as the star witness: Lothar Malskat. Early in the trial, the prosecutor asked Malskat why he had brought the case forward. His blunt response: “Everybody raved about my beautiful murals, yet Fey got all the credit. Nobody even knew my name.”

Malskat and his lawyer didn’t really mount a defense, since he wanted to be found guilty. That would prove to the world that he’d done the paintings. His time on the stand was instead spent disparaging art critics, officials, and others who’d unknowingly praised his work on the restoration of St. Petri-Dom cathedral in Schleswig:

- “One art critic raved about the ‘prophet with the magic eyes.’ It was modeled on my father.”

- “Another gushed about the ‘spiritual beauty of the splendid figure of Mary, so far removed from our present day image of womanhood.’ For that painting I used a photograph of [Austrian film star] Hansi Knoteck.”

- When asked by the prosecutor how a “second-rate painter could have fooled the nation’s leading experts,” Malskat said, “People like to be fooled. We just gave them what they wanted.”

GUILTY AT LAST

After five months of testimony, a verdict was reached in January 1955. The judge said that the case was tricky, because property damage—the basis of a forgery charge—didn’t really come into play. Instead, he said, “The infringement was psychological: Robbery of faith, theft of a miracle.” Fey received 20 months in prison; Malskat got 18 months.

Malskat didn’t serve his sentence right away. After the trial, he escaped to Sweden and tried to make good on his newfound celebrity. Soliciting commissions, he painted the interior of a Stockholm restaurant in the Gothic style (similar to his work on Marienkirche). He also painted the interior of the Royal Tennis Court. What did he paint on the walls there? Turkeys.

After being extradited back to Germany in 1956, Malskat served his 18 months and settled into a quiet life, painting at home and presenting a handful of small gallery shows of his artwork. He died at age 74 in 1988.

As for the frescoes in Marienkirche, they were painted over.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Uncanny Bathroom Reader. This groundbreaking series has been imitated time and time again but never equaled. And Uncanny is the Bathroom Readers’ Institute at their very best. Covering a wide array of topics—incredible origins, forgotten history, weird news, amazing science, dumb crooks, and more—readers of all ages will enjoy these 512 pages of the best stuff in print.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Uncanny Bathroom Reader. This groundbreaking series has been imitated time and time again but never equaled. And Uncanny is the Bathroom Readers’ Institute at their very best. Covering a wide array of topics—incredible origins, forgotten history, weird news, amazing science, dumb crooks, and more—readers of all ages will enjoy these 512 pages of the best stuff in print.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

I liked that guy This is a great article, thanks for the research. Somehow it also comes to my mind the “oh so called wine connoisseurs….”

This is a great article, thanks for the research. Somehow it also comes to my mind the “oh so called wine connoisseurs….”