Dustbin of History: The Green Book

Here’s a piece of recent American history that most people have never heard of. It involves many of the elements we associate with modern life—cars, travel, eating, entrepreneurship…and discrimination. Here’s the story of the Green Book.

Here’s a piece of recent American history that most people have never heard of. It involves many of the elements we associate with modern life—cars, travel, eating, entrepreneurship…and discrimination. Here’s the story of the Green Book.

ROAD TRIP!

For as long as automobiles have been around, they have symbolized freedom and independence. They offered the promise of taking people anywhere they wanted to go, as long as there was a road that went there. For many Americans automobiles did indeed deliver on that promise. But for African Americans living in many parts of the United States in the early and mid-20th century, the automobile was little more than a symbol—that of a freedom that, for them, remained out of reach.

In those years, a trip by automobile for African Americans was an experience all its own, quite unlike car trips taken by white Americans. A black family preparing for a long trip had to pack enough food to get them all the way to where they were going, in case the restaurants along the route refused to serve them—a form of discrimination that was perfectly legal at the time. They had to pack pillows and blankets so that they could sleep in their car if the hotels they stopped at refused to provide them with lodging. They had to put extra cans of gas in the trunk—enough to get them through towns where none of the service stations would sell them gas. And they had to leave enough room in the trunk for a bucket that they could use as a toilet in places where restrooms were reserved for whites only.

KEEP ON MOVING

In some parts of the South, black motorists were advised to keep a chauffeur’s cap handy, so that if a white motorist took offense at their owning a car, perhaps because it was newer or nicer than their own, the motorist could put on the cap and pretend they were driving the car for a white owner. Even passing a slow-moving car on the road could lead to trouble: some white motorists took offense at the idea of dust kicked up by a black-owned car landing on their car. Simply stopping in a town long enough to find out blacks were unwelcome could be dangerous: thousands of towns all over the United States were “sundown towns,” which meant that blacks and other minorities had to be out of the area by sunset. African Americans caught in such a town after dark risked being harassed, arrested, beaten, or killed. In many places the sundown policy was unofficial, but in places like the town of Hawthorne, California, in the 1930s, signs were posted at the city limits with warnings like, “N*****, Don’t Let the Sun Set on YOU in Hawthorne.”

THE LIST

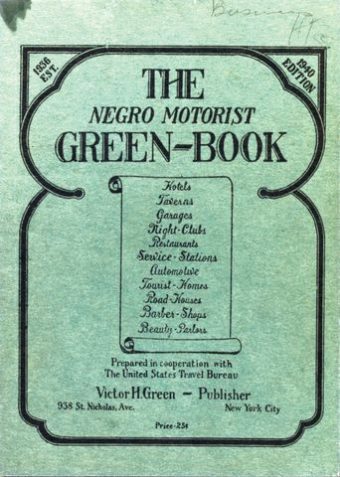

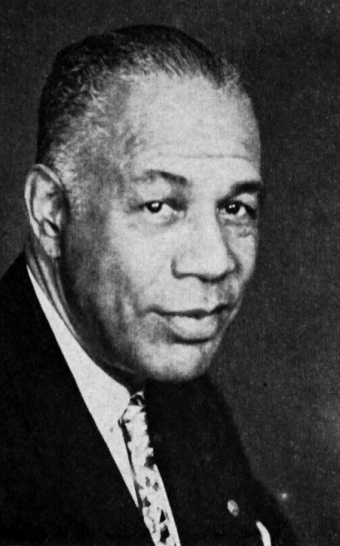

The problem was worst in the South, where segregation was mandated by Jim Crow laws. But as places like Hawthorne, California, make clear, it flourished in other parts of the country as well. New York City was no exception, and it was there in the mid-1930s that an African American mail carrier (and World War I veteran) named Victor Hugo Green decided to do something about it. Inspired by directories published by the Jewish community identifying so-called restricted businesses that did not serve Jews, Hugo decided to create a directory of businesses in the New York City metropolitan area that did not discriminate against blacks. He printed the information in a 15-page booklet called The Negro Motorist Green Book.

The problem was worst in the South, where segregation was mandated by Jim Crow laws. But as places like Hawthorne, California, make clear, it flourished in other parts of the country as well. New York City was no exception, and it was there in the mid-1930s that an African American mail carrier (and World War I veteran) named Victor Hugo Green decided to do something about it. Inspired by directories published by the Jewish community identifying so-called restricted businesses that did not serve Jews, Hugo decided to create a directory of businesses in the New York City metropolitan area that did not discriminate against blacks. He printed the information in a 15-page booklet called The Negro Motorist Green Book.

“This, our Premiere Issue,” Green wrote in the 1937 edition of the Green Book, “is dedicated to the Negro Motorist and we sincerely hope that you will find the many places of reference and information valuable and helpful.” The price of that first edition: 25¢ (about $4 today).

If an African American reader of the Green Book needed some work done on their car, they knew that Gene’s Auto Repairs on West 155th Street would serve them, because the business was listed in the Green Book. Women who wanted a beauty treatment knew they would not be turned away by Bernice Bruton at the Ritz Beauty Salon on 7th Avenue. “Why Do So Many People Dine at Julia’s?” asked one paid advertisement. “Because She Has Excellent Food, Well Served at Most Reasonable Prices,” including daily dinners for 35¢, and Sunday dinners for 50¢. A couple eager for a night out could go to the Donhaven Country Club in Westchester County, which offered dinner dances with live music by Goldie Lucas and his Donhaven Country Club Band. The Green Book also provided listings for pharmacies, barbershops, cleaners, liquor stores, golf courses, and vacation spots, plus lists of state parks and points of interest, tips on safe driving and auto care, and any other information that Green thought would be useful to motorists.

HERE, THERE, EVERYWHERE

The 1937 edition proved so popular with readers that for the 1938 edition Green decided to expand the scope of the publication to include every state east of the Mississippi River. Then in 1939 he expanded it to the entire nation. For help with compiling the listings, he turned to his fellow mail carriers. They knew which businesses did and did not discriminate, which barbers gave the best haircuts, and which restaurants served the best food at reasonable prices. In communities where there were few or no hotels that provided accommodations to African Americans, the mail carriers submitted a new type of listing: “tourist homes,” or private homes whose owners rented rooms to travelers.

Year by year, as more listings were sent in, the Green Book grew from 15 pages to more than 80, including entries for Canada, Mexico, and eventually even Bermuda, an island chain in the Atlantic popular with tourists. Later editions had the slogan “Carry Your Green Book With You—You May Need It” on the cover, along with a quote from Mark Twain: “Travel is Fatal to Prejudice.”

Over time, the number of copies sold grew, eventually reaching 15,000 copies a year. They could be ordered directly from Hugo Green or purchased through the businesses listed in the Green Book. They were also distributed through Esso service stations, which marketed the guides using the slogan “Go Further With Less Anxiety.” At a time when other service station chains, including Shell, refused to even sell gasoline to black motorists, Esso awarded service station franchises to blacks and had African American executives on its corporate staff. (Esso changed its name to Exxon in 1973.)

MUST-READ

Copies of the Green Book were essential reading not just for vacationers but also for African Americans who made their living on the road, including salesmen, musicians, and baseball players in the Negro Leagues. When the civil rights movement began in the mid-1950s, leaders of the movement began to use them as well. The guides probably saved many lives by steering motorists away from trouble and toward the businesses that would accommodate them.

Green also provided a “Vacation Reservation Service” to assist his readers with booking rooms and other services. He accomplished all of this while still delivering the mail during the day, and serving customers at the Green Book offices in the evenings from 8:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. It wasn’t until he retired from his job at the post office in 1952 (after 39 years) that he was able to focus entirely on the Green Book.

PLANNED OBSOLESCENCE

As successful as the Green Books were, Green told his readers that he actually looked forward to going out of business someday. “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published,” he wrote. “That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please.”

Green did not live quite long enough to see it: he passed away in 1960. But his widow, Alma, continued to publish the guides after his death, and she was the one who lived to see the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which made it illegal for businesses to discriminate against their customers on the basis of race.

With the passage of that law, for the first time in history African Americans had the freedom and the right to travel, buy gasoline, eat in restaurants, and obtain lodging anywhere they pleased. They no longer needed lists of businesses that were willing to serve them, now that all businesses were required by law to do so. Just as Hugo Green had predicted, the Green Book soon became obsolete, and ceased publication in 1966.

GREEN DAYS

For three decades, the Green Book had been an institution in the black community, as indispensable for the traveler as a road map, but they soon faded into obscurity. It had long been routine for subscribers to toss out last year’s Green Book as soon as the new year’s edition became available. When the Green Book itself became obsolete, many of the last copies were tossed out with the trash. Not surprisingly, few survive today. As interest in the publication has grown in recent years, the value of the surviving copies has risen substantially. The Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture has a copy of the 1941 Green Book in its collection. It originally sold for 25¢; the Smithsonian paid $22,500 for it in 2015.

Copies of the Green Book may still survive today in private homes, cultural and historical treasures hiding in plain sight, waiting to be discovered. If you happen to find one lying around, hang on to it—or better yet, donate it to a museum. It’s a living piece of American history, and a testament to one man’s three-decade mission to secure the blessings of liberty for everyone.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Uncanny Bathroom Reader. This groundbreaking series has been imitated time and time again but never equaled. And Uncanny is the Bathroom Readers’ Institute at their very best. Covering a wide array of topics—incredible origins, forgotten history, weird news, amazing science, dumb crooks, and more—readers of all ages will enjoy these 512 pages of the best stuff in print.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Uncanny Bathroom Reader. This groundbreaking series has been imitated time and time again but never equaled. And Uncanny is the Bathroom Readers’ Institute at their very best. Covering a wide array of topics—incredible origins, forgotten history, weird news, amazing science, dumb crooks, and more—readers of all ages will enjoy these 512 pages of the best stuff in print.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|