The Greatest Trade in Sports History

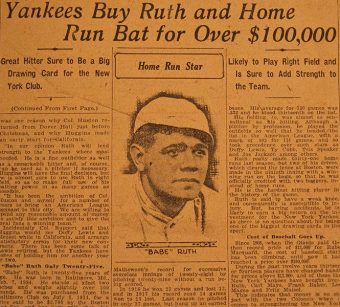

It was 97 years ago this year when the Boston Red Sox gave the New York Yankees a late Christmas present. On December 26th, 1919, Sox of Boston sold their star pitcher and emerging slugger George Herman “Babe” Ruth to the Yankees of New York for an eventual sum of either $100,000 or $125,000 (the exact amount is disputed), or about $1.2-$1.5 million today, to be paid in $25,000 installments. In announcing the sale to the media, Red Sox president and owner Harry Frazee said he would have rather taken players, but no team “could have given me the equivalent in men without wrecking itself.” So, he happily took the “enormous” amount of cash that the Yankees offered, quipping that “I do not mind saying I think they are taking a gamble.”

It was 97 years ago this year when the Boston Red Sox gave the New York Yankees a late Christmas present. On December 26th, 1919, Sox of Boston sold their star pitcher and emerging slugger George Herman “Babe” Ruth to the Yankees of New York for an eventual sum of either $100,000 or $125,000 (the exact amount is disputed), or about $1.2-$1.5 million today, to be paid in $25,000 installments. In announcing the sale to the media, Red Sox president and owner Harry Frazee said he would have rather taken players, but no team “could have given me the equivalent in men without wrecking itself.” So, he happily took the “enormous” amount of cash that the Yankees offered, quipping that “I do not mind saying I think they are taking a gamble.”

Nearly a century later, this still remains the most famous – and lopsided – trade in sports history. Of course, Babe Ruth went on to become one of the most famous athletes in history while leading the Yankees to four world championships over his 15 season tenure with the team. The Red Sox, after winning three World Series with Ruth, would not win again until 2004- an 86-year drought. Here’s the story of how it all went down 97 years ago and why the Red Sox chose to sell the best player in baseball in the first place.

George Herman Ruth was born poor on February 6, 1895 in Baltimore to a saloon owner and a mother of failing health. As a young boy, he was largely unsupervised and was generally regarded as a troublemaker. When he was nine, he was sent to St. Mary’s Industrial School (now the site of a hospital and baseball field). That’s where he was introduced to the game of baseball by a Canadian-born priest named Brother Mathis, who Ruth would later call “the greatest man I’ve ever known.”

On the diamond is where Ruth found his calling, lightyears ahead of his young peers in every facet of the game from fielding to pitching to hitting. He was quickly signed by his hometown minor league team the Baltimore Orioles (where he got his famed nickname because of his boyish looks and manner). Five months later, he was sold to the Boston Red Sox. At 19 years old, Ruth was a major leaguer and made his pitching debut on July 11, 1914.

While immensely skilled, Ruth struggled with being away from home for the first time. When in Baltimore, he was often able to go back to St. Mary’s for guidance and counseling from Brother Mathis. But there was no Brother Mathis in Boston. The older players – like Smokey Joe Wood and Tris Speaker – weren’t exactly the best influences and not particularly friendly to the young Ruth either, giving him the nickname “The Big Baboon.” This was a reference to his stature and a not-so-vague racial epitaph in regards to the rumor that Ruth was, in fact, African-American.

He began going out at night with teammates, often drinking too much and staying out too late. But he was talented. Even after spending a good deal of the summer sitting on the bench and playing in Providence (Boston’s minor league team), he emerged in 1915 as one of the best pitchers in baseball. Going 18-8 with an ERA 2.44 (which was, for more modern fans, an ERA+ of 114), he helped lead the Red Sox to the 1915 world championship.

Still, trouble was afoot. The twenty-year-old had just gotten a raise and was taking full advantage of being a well-paid professional athlete. As the 2007 biography “The Big Bam: The Life and Times of Babe Ruth” put it, “(He) was a kid let loose in an adult funhouse….Nights only ended when morning arrived… Money removed the last of his few inhibitions.” (For more on this, see our article: Babe Ruth- The Ladies’ Man.)

He was beloved by some teammates and hated by others for his loud, profane and uncontrollable attitude. In fact, teammates started calling him “Two Head” in a reference to his literal and figurative large head. While the team and coaches did what they could to corral him a bit, they didn’t do enough. After all, he was too good and too important to the team to impose real consequences on his potentially destructive behavior.

In 1916, Ruth was even better and the Red Sox won the World Series again. However, again, Ruth’s social life threatened his baseball career. Despite getting married the year before, his late night partying and womanizing increased. Ruth was just as good of a player in 1917 and pitched his only no-hitter, but that year he also started hitting. While he didn’t play everyday, he occasionally pinch hit – and often knocked the cover off the ball.

In 1918, after battling with the coaching staff about more playing time, he was finally inserted into the lineup and began, as SABR puts it, “likely the greatest nine- or ten-week stretch of play in baseball history,” while also continuing a dominating stretch of pitching. After another championship, Ruth should have been a Red Sox for life. But he wasn’t. In 1919, the Red Sox lost more games than they won (due, in large part, to pitching injuries) – despite Ruth setting the all-time record for most home runs in a single season at 29.

The reasons for selling Babe Ruth’s contract were numerous and went beyond his behavior. For one, he saw his own future as a power-hitting everyday player, not a pitcher who played only every few days. Ruth hated sitting on the bench and knew that he was as valuable – if not more so – hitting and playing the field every game. The Red Sox declined to see it this way. After 1919’s lost season because of injuries to pitchers, the Sox felt like they had to have Ruth on the mound.

In addition, decreased attendance to Fenway Park resulting from the Red Sox’s poor season and, partially, the aftereffects of World War I made owner Frazee a bit worried about money. He also felt Ruth’s constant demands for a pay raise were not only out of line, but something he simply could not afford anymore. There was also the matter of the relationship between Frazee and Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert, who had fought the American League’s founder Ban Johnson in court for not disclosing his stakes in other competing teams. Frazee and Ruppert were friends, making a deal between the two teams more easily sorted out. To validate this, a side deal (that could have never happened today) was struck where Ruppert took on Frazee’s Fenway Park mortgage for a short time as a secret thank you for selling him the best player in baseball.

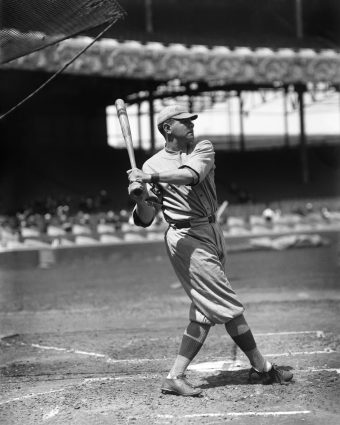

Even if Ruth’s talents were undisputed, the trade wasn’t immediately cursed in Boston. Many fans knew of Ruth’s late-night galvanizing and heavy indulgences. There was a fear that he would party himself out of baseball sooner than later. (And, indeed, the once chiseled physique of Ruth’s early years, see picture to the right, was already beginning to balloon into the tubby persona we all remember today.) Frazee seized upon this, using the excuse that Ruth was a loose cannon and had too much of an ego as the reason for the trade. On top of that, while he had proved his exploits as a hitter, there was a sense that pitching was more important than hitting anyway in the so-called “Dead Ball Era.” What no one saw coming was that Ruth, nearly by himself, would turn baseball into a hitting sport.

Even if Ruth’s talents were undisputed, the trade wasn’t immediately cursed in Boston. Many fans knew of Ruth’s late-night galvanizing and heavy indulgences. There was a fear that he would party himself out of baseball sooner than later. (And, indeed, the once chiseled physique of Ruth’s early years, see picture to the right, was already beginning to balloon into the tubby persona we all remember today.) Frazee seized upon this, using the excuse that Ruth was a loose cannon and had too much of an ego as the reason for the trade. On top of that, while he had proved his exploits as a hitter, there was a sense that pitching was more important than hitting anyway in the so-called “Dead Ball Era.” What no one saw coming was that Ruth, nearly by himself, would turn baseball into a hitting sport.

After the trade was made, Ruth negotiated a contract that easily made him the highest paid player in baseball history. He did not disappoint in his first season with the New York Yankees, leading the American league in eight offensive categories and helping the Yankees become the first team in history to attract more than a million fans to the ballpark. He also led the league with an astonishing 54 home runs. The next closest home run hitter that year had only 19. In 1921, the Ruth-led Yankees to the first of seven American League pennants in a 12-year span, which included four World Series wins.

The impact of the Babe Ruth trade has resonated for nearly a century. Since 1920, the Yankees have won 40 pennants, 27 World Series and the club is generally regarded as the most successful team in baseball history. The Red Sox have won only 7 pennants and 3 World Series in that time. While “The Curse of the Bambino” may have technically ended in 2004 when the Red Sox defeated the St. Louis Cardinals (after beating the Yankees in a dramatic, for-the-ages pennant-winning comeback) for their first World Series in over eight decades, December 26th still looms very large in the sport’s history.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- “The Black Babe Ruth”

- That Time After Facing One Batter, Babe Ruth Punched the Umpire and His Replacement Threw a No-Hitter

- There Once was a 17 Year Old Girl Who Struck Out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig Back to Back

- Baby Ruth Candy Bars Actually Were Named After Babe Ruth

- The Story of the U.S. National Anthem and How It Became Part of the National Pastime

| Share the Knowledge! |

|