The Duel That Wasn’t

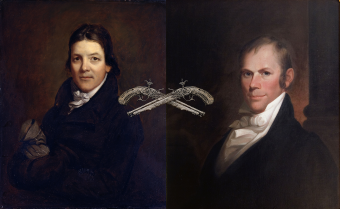

It was a beautiful spring day on the banks of the Potomac River in 1826 when Secretary of State Henry Clay and Senator John Randolph of Roanoke counted paces, cocked their guns and prepared to fire at one another. The two notable American politicians were engaged in an illegal duel that, by nearly all accounts, should have never happened. Shots rang out, but the duel ended with neither harmed. Thus, it earned the moniker “The Duel That Wasn’t.” Here’s how this odd moment in American history came to pass.

It was a beautiful spring day on the banks of the Potomac River in 1826 when Secretary of State Henry Clay and Senator John Randolph of Roanoke counted paces, cocked their guns and prepared to fire at one another. The two notable American politicians were engaged in an illegal duel that, by nearly all accounts, should have never happened. Shots rang out, but the duel ended with neither harmed. Thus, it earned the moniker “The Duel That Wasn’t.” Here’s how this odd moment in American history came to pass.

In 1826, Henry Clay was one of America’s most well-known politicians. Starting his career as a flamboyant Kentucky lawyer with a knack for courtroom oratory, he was elected to Kentucky’s House of Representatives at only 26 years old. Three years later, he was asked to serve as Senator when the previous one resigned. He took the job in 1806, despite the fact that he didn’t meet the constitutionally eligible age of 30. Fortunately for Clay, no one seemed to notice (including, reports say, Clay himself).

He rose through the ranks to become Speaker of the House, where he advocated for the War of 1812 against Great Britain. In this role and as Secretary of State starting in 1825, Clay became known as the “Great Compromiser” due to his ability to sympathize with both sides of many issues and come up with solutions that could bring the sides together. There was no better example of this than 1820s Missouri Compromise, which admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state into the union. (Clay, himself, was a slave owner, but believed that slavery would die out on its own eventually, as had been the viewpoint of many of the founding fathers.)

John Randolph was also quite notable, but more for his erratic behavior than any political maneuvering. Born into a prominent Virginia family and a disciple of Thomas Jefferson (who was also his cousin), he believed passionately in states’ rights and detested federal authority (think a 19th-century version of a libertarian). Mean, bad tempered, insulting and violent, historians think Randolph was an alcoholic and, possibly, an opium addict. Even many of his supporters suggested that he might be insane.

Today, some historians believe this behavior may have stemmed from his insecurity relating to health issues and sexual orientation (though, there are accounts about him nearly marrying a woman). It has been speculated that he suffered from Klinefelter’s syndrome; those with this condition are usually considered and identify as male, but have an extra X chromosome (XXY), which, among other things, interferes with sexual development.

Whether he really had this condition or not, it is noted that Randolph was unable to grow a beard and had a very high pitched voice, not unlike a pre-pubescent male. Due to his boyish traits, at one point Congressman Willis Alston referred to Randolph as a “puppy,” resulting in Randolph attacking Alston with a cane right in the Capitol Building. Given how badly he bloodied up Alston, today this would have seen Randolph serving time in prison. At the time, however, he was merely given a small fine of $20 for the attack (about $300 today).

A lifelong bachelor, one biographer speculated that Randolph had “nurtured a crush on Andrew Jackson,” another famous short tempered individual in American history. For instance, before becoming President, Jackson once killed a man for simply calling Jackson a “worthless scoundrel, a poltroon, and a coward.” In another incident while President, one Richard Lawrence attempted to assassinate Jackson, but his guns misfired. The enraged President subsequently began beating Lawrence furiously with a cane until people nearby pulled Jackson off him.

In any event, it was during a debate on executive powers in the Senate on March 30, 1826 that Randolph went off on a rant that was all-too-familiar to many in attendance. In the crosshairs of his insults were President John Quincy Adams and Secretary of State Clay. Accusing both of manufacturing evidence to support America’s participation in the Congress of Panama, he called them corrupt, unscrupulous and immoral. Going further, he personally attacked both by saying they were the “puritan with the blackleg,” an epithet that was a reference to the 18th-century novel Tom Jones, defined as a dishonest card cheat. If that wasn’t enough, he took a shot at Clay’s forebears saying they should be held responsible for bringing into the world, “this being, brilliant yet so corrupt, which, like a rotten mackerel by moonlight, shined and stunk.”

As expected, all of this greatly upset Clay, who was a prideful person himself. However, there was a tradition of the day that words spoken during a congressional session by a congressman or a senator, even if they were of the utmost insult, could not be used to incite a duel. This was essential to keep senators and congressman from having to frequently fight in duels with their peers in a period where a choice insult against a gentleman of honor would sometimes require the defending of that honor via a duel. Because of this tradition, Randolph thought he could say these things without serious consequence.

But Clay didn’t see it this way. It’s unclear if Clay ignored the tradition or thought that Randolph had somehow waived this so-called “special privilege” in some way, but he challenged the Senator to a duel anyway.

At this point, Randolph could have reminded Clay of this privilege and not accepted the duel and still saved face. That’s not what he did, however. He accepted the duel and then widely complained that Clay was out of line challenging him in the first place. Despite supporters on both sides trying to convince both distinguished gentlemen to back down, they set the duel date for April 8, 1826.

This wasn’t Clay’s first foray into dueling. 17 years earlier, Clay was called a liar by Humphrey Marshall (Supreme Court Justice John Marshall’s cousin) on the floor of the Kentucky House of Representatives. To defend his honor, Clay challenged him to a duel. The two Kentuckians met at Silver Creek, where it empties into the Ohio River. Marshall was grazed on the first shot, but Clay was severely wounded in the thigh by the third shot. Bleeding profusely, he insisted the duel continue, but his aides and Marshall both said enough. Clay, of course, would recover.

Despite accepting the challenge and his harsh words against Clay, Randolph never had any intention of hurting him. The only reason he agreed to the duel was out of principle. He privately told friends that he had an “entire unwillingness” to make a widower of Mrs. Clay. In fact, he assured fellow senator Thomas Hart Benton “in tones as sweet as woman’s own” that he would “do nothing on the morrow to disturb the sleep of the child or the repose of the mother” to Clay – unless, of course, he saw “the devil in Clay’s eye.”

You see, despite his own promises to not harm Clay, Randolph wasn’t positive Clay would return the favor. As such, during negotiations in regards to the duel, Randolph asked for it to take place on Virginia soil – as opposed to Washington DC or Maryland – because if he was going to die, he wanted to die in his home state (even though, it was illegal to duel in Virginia.) The Clay camp accepted this request, despite Virginian laws.

As for Clay, it is not clear today what he was thinking in the days leading up to the duel, though it isn’t thought that he knew of Randolph’s private vow to not harm him in the duel.

At 4 PM on the Virginia side of the Potomac (in today’s Arlington), the two men stood apart from each other. Each brought a surgeon, in case of injury. Randolph confidently assured his men that he could tell that “Clay was calm and not vindictive” and he did not see “the devil in his eye.”

Counting off paces (ten or thirty, accounts differ), they turned to one another. Then, all of sudden, a gun went off. It was Randolph’s, an accidental discharge due to a hair trigger and his bulky gloves. Luckily, it was pointed towards the ground.

A bit spooked – again, Clay didn’t know of Randolph’s non-violent intentions – they agreed to dismiss the accident and count off again. The word was then given and both turned and shot. Randolph’s first shot was wild, as he’d promised. On the other hand, Clay’s shot was somewhat true, putting a sizable hole through Randolph’s intentionally massively oversized overcoat.

Realizing that his opponent had come only inches from seriously wounding and perhaps killing him, Randolph decided to broadcast his peaceful intentions and shot his second bullet harmlessly into the air. Seeing this, Clay called off the duel.

Both men walked to the middle and shook hands, but not before a few more words exchanged. Clay, rather apologetically, reportedly told Randolph, “I trust in God, my dear sir, you are untouched; after what has occurred, I would not have harmed you for a thousand words.” Always sharp tongued, Randolph motioned to his coat and answered dryly, “You owe me a new coat, Mr. Clay.” Clay reportedly responded, “I am glad the debt is no greater.”

Henry Clay went on to become a defining figure in 19th-century American political history. Becoming Senator (again) and running for President several times, he helped pull the country back from the brink of civil war. He died in 1852. 13 years later, the deadliest conflict in American military history broke out, echoes of which we still feel today.

John Randolph of Roanoke (he actually preferred this add-on to his name) was appointed to be the Minister to Russia by President Andrew Jackson in 1830. Three years later, he died of what was reported as tuberculosis, but findings contend that he was drinking heavily and engaging in heavy opium use at the time of his death.

To this day, no one knows if Clay ever purchased Randolph a new coat.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The First Person to Use the Temporary Insanity Defense was a Congressman Who Murdered the Son of the Composer of “The Star Spangled Banner”

- In Which Alexandre Dumas’ Pants Fall Down During His First Duel

- The Duels Fought Over Marie Curie

- How a Donkey and an Elephant Came to Represent Democrats and Republicans

- When Lincoln Was Almost Assassinated Nine Months Before He was Assassinated

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

A fine, fascinating article, except 13 years after 1852 would be 1865. That’s the year the Civil War ended, not when it began.

wow, dueling sounds like such a crazy activity, good article

Randolph’s “mackerel by moonlight” comment was not made about Henry Clay, but rather Secretary of State Edward Livingstone.