Who – or What – was the First Sports Mascot and How Did the Practice Start?

During lopsided games or pauses in action, it is the sports team’s mascot that keeps fans entertained. Be it with dancing, shooting t-shirts into the crowds or goading opposing coaches into attacking them, mascots make sports a little more fun – even if a few of them gives kids nightmares.

During lopsided games or pauses in action, it is the sports team’s mascot that keeps fans entertained. Be it with dancing, shooting t-shirts into the crowds or goading opposing coaches into attacking them, mascots make sports a little more fun – even if a few of them gives kids nightmares.

While we tend to think of mascots as distinctly American, even the San Diego Chicken can trace his origins to 19th century France. You see, the word “mascot” probably derives from the French word “mascoto,” meaning “witch, fairy or sorcerer.” This, in turn, gave rise to the slang word “mascotte,” meaning “talisman” or “sorcerer’s charm” in the 1860s. It was often used in the context of gambling, in hopes that a “mascotte” was there to pull luck to the bettor’s side.

The word was first popularized and brought to the mainstream by the 1880s French opera “La Mascotte,” written by playwright Edmond Audran. The opera was about an Italian farmer whose crops just wouldn’t grow- that is, until he’s visited by a mysterious virgin named Bettina who, as long as she remains a virgin, functions as something of a good luck charm. With her help, his fortunes soon turn around.

It’s hard to decipher who – or what – was the first sports mascot. According to esteemed etymologist Barry Popik, the word “mascotte” was first used in the context of a good luck charm in sporting events around the 1880s in American baseball. According to The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, the first use of it was in an 1883 issue of The Sporting Life about a boy named “Chic,” who carried bats and ran errands for the players. Beyond his practical usefulness, the players also considered him a good luck charm. As Sporting Life wrote, “the players pin their faith to (Chic’s) luck-bringing qualities.”

As for the first animal mascots (of sorts), in an 1884 edition of the Cincinnati Enquirer, seemingly in regards to a goat wandering around their baseball team, there is this line, “The goat was probably looking for some show-bills, oyster-cans, or some other usually palatable dish for his stomach, but the audience could not see it in that light, and thought he was even a better ‘Mascotte’ than the old-time favorite.”

In an 1884 issue of Sporting Life, there’s also a reference to a mascot involved in the Boston’s baseball team recent ability to win games, “Have the Bostons a Mascotte? They have crawled out some very small holes the past two weeks.”

Two years later, Sporting Life again connected the word to being a good luck charm, but dropped the “e” getting us closer to the modern day spelling- “Little Nick is the luckiest man in the country, and is certainly the Browns’ mascott.”

In 1886, the New York Times dropped the extra “t,” marking the first known time the modern word “mascot” is used. The reference was about a boy named Charle Gallagher who was “said to have been born with teeth and is guaranteed to possess all the magic charms of a genuine mascot.”

In 1886, the New York Times dropped the extra “t,” marking the first known time the modern word “mascot” is used. The reference was about a boy named Charle Gallagher who was “said to have been born with teeth and is guaranteed to possess all the magic charms of a genuine mascot.”

In yet another 1886 reference that used the modern spelling, The Chicago Tribune noted on June 18th of that year,

(T)he Chicago players and their mascot marched down the platform and placed themselves at the head of the double column of visiting Chicagoans that had formed at the depot, and then with their brooms elevated, the delegation marched out of the depot…The odd looking procession, extending nearly two squares, attracted a vast amount of attention…. [They] were escorted to the ground by a band, and entered the field behind little Willie Hahn, who carried an immense broom on which were the words ‘Our Mascot.’

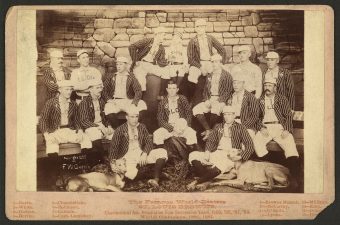

In any event, in late 19th century and into the early part of the 20th century, it appears that all sports mascots were children or real animals and, contrary to the version of the mascot we have today, they were taken very seriously. For instance, the 1888 St. Louis Browns’ team photo featured a little, uniformed boy and two dogs, all three given ample credit for being part of the team that was nicknamed the “World Beaters.”

In any event, in late 19th century and into the early part of the 20th century, it appears that all sports mascots were children or real animals and, contrary to the version of the mascot we have today, they were taken very seriously. For instance, the 1888 St. Louis Browns’ team photo featured a little, uniformed boy and two dogs, all three given ample credit for being part of the team that was nicknamed the “World Beaters.”

The first football mascot may have been Handsome Dan, a bulldog that belonged to a member of the Yale class of 1892. 126 years later – and 17 bulldogs (as of this writing, the university is searching for the 18th) – Handsome Dan is still Yale’s mascot, with a statute and a Shake Shack hot dog to his name.

The 1919 Chicago White Sox credited a physically disabled orphan named Eddie Bennett for providing them enough luck to win the American League pennant. This was the same year of the infamous “Black Sox” scandal involving several players on the team conspiring with gamblers to intentionally throw the World Series. Unfortunately for the rest of the team, Bennett’s luck couldn’t overcome their efforts.

As for the professional mascots we have today, the first sports mascot that made a career out of it (in other words, wasn’t a kid or an animal) is generally thought to be Max Patkin, known as the “Clown Prince of Baseball.” Patkin began his mascot career as an actual baseball player, pitching for a White Sox minor league team. He ended up on a Navy team during World War II and once, during an exhibition in Hawaii, he found himself pitching to the great Joe DiMaggio. Legend has it that Patkin served up a pitch that the Yankee Clipper hammered for a home run. On a whim as DiMaggio rounded the bases, Patkin followed. Mocking his trot and making goofy faces- the crowd loved it.

Such antics were not unheard of back then. For instance, Major League Baseball player Herman “Germany” Schaefer once stepped up to bat wearing a raincoat and galoshes, along with carrying an umbrella to hit with instead of a bat- he was hinting to the umpire that maybe they should call the game due to the rain… You can read more about his many antics here: There Once was a Major League Baseball Player Who Stole First From Second.

As for Patkin, his playful mockery of DiMaggio began a nearly five-decade career entertaining baseball crowds.

While Patkin did have his traditional garb – loose uniform, sideways hat, and goofy expression – it wasn’t a costume per say, so he wasn’t the first there. The first live costumed mascots were probably Mr. Met in baseball and Brutus Buckeye in college football, both debuting in 1964. But it was a chicken that plucked his way into American hearts and made the idea of a costumed mascot a staple of sporting events.

It all started as a cartoon. In 1974, the San Diego rock station KGB hired cartoonist Brian Narelle (who would also star in John Carpenter’s first movie Dark Star) to create a character for a series of commercials. He drew a chicken…

It was such a hit that the radio station created a colorful chicken costume to go along with it, one that debuted on Easter handing out eggs at the San Diego Zoo. In need of a person to go inside of the costume, they found a journalism student paid two dollars an hour (about $11.40 today) for the gig. His name was Ted Giannoulas. He was so good at being the chicken he was asked to come to Padre games to entertain the crowds.

Thus began an over forty year career as the most influential mascot in American sports history – the San Diego Chicken. Dancing, goofing off and emerging from eggs, many credit the Chicken and Giannoulas for creating the modern mascot.

Influenced by the chicken, other sports teams created mascots to promote and cheer on their teams. In 1977, the Phillie Phanatic (designed by the same person who created Miss Piggy) made his debut. The Oriole Bird hatched a year later in Baltimore. By the mid-1980s, many baseball, football, soccer, college athletic teams across the globe had dancing, costumed mascots. Even the Olympics had their own mascots starting in 1968 (the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics was the first to have a living, costumed mascot).

Today, seemingly every pro, college and high school sports team has a mascot. There’s even a Mascot Hall of Fame, which is in the midst of opening a brand new facility in 2017 in Whiting, Indiana. And they owe it all to rampant superstition among sporting enthusiasts and athletes along with a rather obscure 1880s French opera about a curious virginal good luck charm- all culminating in a gyrating banana slug being a thing to celebrate.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Who Invented the Sporting Wave?

- The Forgotten Mascot: The Frito Bandito

- How a Donkey and an Elephant Came to Represent Democrats and Republicans

- Why Do Baseball Managers Wear the Team’s Uniform Instead of a Suit Like In Other Sports?

- Why are Boxing Rings Called Rings When They Are Square?

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

The Edmonton Eskimos, of the Canadian Football League, had costumed mascots starting in 1972. (I know that to be the case as I was one of them)