The Strange Fate of Ted’s Head

Ted Williams’s lifelong dream was to be known as “the greatest hitter who ever lived.” It’s sad, then, that today many people know him as “that baseball player who got cryonically frozen.”

Ted Williams’s lifelong dream was to be known as “the greatest hitter who ever lived.” It’s sad, then, that today many people know him as “that baseball player who got cryonically frozen.”

HEADING FOR HOME

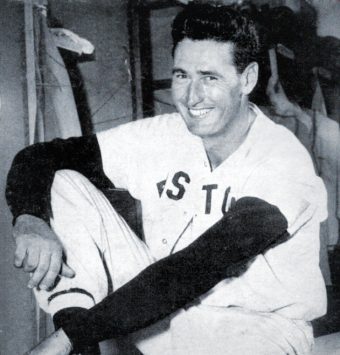

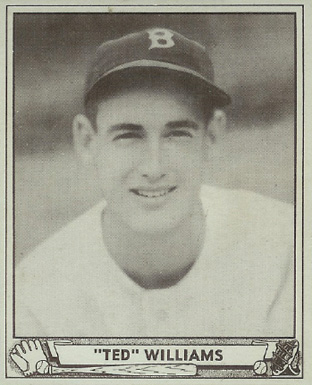

In the summer of 2001, some old friends went to Hernando, Florida, to pay a visit to Ted Williams, the legendary Red Sox slugger and the last major league player to bat over .400. The “Splendid Splinter” was 83 years old and in poor health; in recent years he’d battled heart disease, strokes, and a broken hip. Now nearly blind, Williams required round-the-clock nursing care and could only get around with the aid of a walker. But his spirits were high as he visited with his friends, and when one of them pointed to a photograph of Slugger, a beloved Dalmatian that had died in 1998, Williams told them that he was saving the dog’s ashes so that when he died, they could be scattered together in the waters at one of his favorite fishing spots.

The old ballplayer’s health deteriorated further over the next year, and on July 5, 2002, he died. Just as he’d told his his friends, his will instructed that his remains “be cremated and sprinkled at sea off the coast of Florida where the water is very deep.”

COLD STORAGE

It wasn’t to be. Even as Williams lay dying, a “standby team” dispatched by an organization called the Alcor Life Extension Foundation was at his bedside, waiting patiently for him to breathe his last. Within moments of his being declared dead at 8:49 a.m., the team sprang into action, pumping his body full of blood thinners and packing it in a body bag filled with dry ice for the trip to a nearby airport, where a chartered jet stood by to take it to Alcor headquarters in Scottsdale, Arizona.

By 11:30 p.m. Williams’s body was stretched out on the Alcor operating table. There, in a procedure lasting 37 minutes, a surgeon decapitated the corpse so that head and body could be frozen separately in “dewars,” high-tech steel thermoses filled with liquid nitrogen. Over the next several days, his head and body were slowly chilled to -320°F, and they’ve been floating in what Alcor calls “long-term storage” ever since. Williams’s head reportedly sits in a dewar on a shelf; the rest of his body floats in a much larger dewar several feet away.

CRYONICS 101

The purpose of freezing bodies “cryonically,” as advocates call it, is to halt decay and preserve the body in as intact a form as possible, in the hope that someday medicine will be able to cure the dead person’s illnesses and reverse the aging process. When that day comes, the person can be thawed out, resuscitated, and restored to a second youthful, vigorous life.

The cryonics movement has been dismissed by mainstream scientists as a hopeless, pseudoscientific pipe dream. Even if cryonic freezing is perfected at some point in the future, critics argue that modern techniques are so primitive and toxic, and inflict so much irreversible damage, that resuscitation of people frozen today will likely never be possible. Even Alcor requires clients to sign forms acknowledging that resuscitation may never happen…but that hasn’t stopped more than 800 living people from signing up to be cryonically frozen when they die. As of 2007, approximately 80 of them have died and been put into long-term storage at Alcor’s facilities in Scottsdale. Scores more have signed up for similar procedures at other cryonic organizations in the United States and Europe. Worldwide, it’s estimated that fewer than 500 people have been cryonically frozen so far, but thousands more customers are ready to go the moment their “first life cycle,” as cryonics enthusiasts put it, comes to an end.

SON OF A GUN

So how did Ted Williams end up at Alcor? We’ll probably never know for certain whether he changed his mind in the final months of his life and opted for cryonic preservation without updating his will, as his son John-Henry Williams claimed, or if John-Henry, acting as his father’s power of attorney, had the old man frozen against his wishes.

John-Henry, who was 33 at the time of his father’s death, was Ted’s middle child and only son, one of two children he fathered with Dolores Wettach, his third wife. For most of John-Henry’s life, he and his father had not been close. Ted and Dolores divorced when the boy was only four, and he and his sister Claudia were raised by Dolores on her family’s farm in Vermont. Father and son began to grow closer in the early 1990s when John-Henry, fresh out of college, stepped in to manage his father’s business affairs after Ted, then in his mid-70s, was swindled out of millions of dollars by a business partner who turned out to be a con man.

WHO’S IN CHARGE?

Over the next few years, John-Henry gradually took control over nearly every aspect of the old ballplayer’s life, shutting out many friends, family, and loved ones in the process. He turned his father into a one-man sports memorabilia franchise, badgering him to spend hours a day autographing photos, jerseys, baseballs, bats, and other merchandise—entire cases of the stuff, day in, day out, even after Ted’s health began to fail. John-Henry also filled his father’s schedule with more paid public appearances at card shows and other events than Ted had ever attended before.

At the time, Ted was one of the biggest names on the card show circuit—photos signed by him routinely sold for $300, baseballs went for $400, bats for $800, and jerseys for $1,000. John-Henry claimed that pushing his father to sign hundreds of signatures a day was therapeutic, and that it kept the old man’s mind on baseball. Ted’s home-care nurses thought he was being abused, but when they spoke out John-Henry fired them on the spot.

At the time, Ted was one of the biggest names on the card show circuit—photos signed by him routinely sold for $300, baseballs went for $400, bats for $800, and jerseys for $1,000. John-Henry claimed that pushing his father to sign hundreds of signatures a day was therapeutic, and that it kept the old man’s mind on baseball. Ted’s home-care nurses thought he was being abused, but when they spoke out John-Henry fired them on the spot.

HANDS OFF

When the old slugger was hospitalized in January 2001 for complications from open-heart surgery, John-Henry gave strict instructions that the nurses not insert IVs into his right arm or do anything else that might impair that arm’s range of motion.

Then, when Ted was released and began to receive physical therapy at home, “all of the exercises, all of the work, were being done to restore strength and mobility to his right hand,” Leigh Montville writes in Ted Williams: The Biography of an American Hero. Why focus so much attention on the right hand? “So he’ll be able to sign autographs again,” John-Henry explained.

ANOTHER BRIGHT IDEA

It was at about this time that Ted Williams’s oldest daughter, Barbara Joyce (Bobby-Jo) Ferrell, says that her half brother John-Henry came to her with an idea of how to keep the income flowing in long after their father was no longer able to sign his name. “Have you ever heard of cryonics?” she says John-Henry asked her. “Wouldn’t it be neat to sell Dad’s DNA? There are lots of people who would pay big bucks to have all these little Ted Williamses running around.” Bobby-Jo recoiled at the thought and called John-Henry “insane.” Her concerns did not diminish when John-Henry assured her, “We don’t have to take Ted’s whole body. We can just take the head.”

LIKE DAUGHTER, LIKE FATHER

Leigh Montville describes how a home-care nurse overheard John-Henry pitching cryonics to his father more than a year before the old man died. “You’re outta your %@#&! mind,” Ted reportedly told his son. “What about just your head?” John-Henry asked. Ted’s angry response, as he walked back to his room: “%@#& you!” (That nurse was fired in May 2001.)

It isn’t clear whether John-Henry really did manage to sell his father on the merits of cryonics in the last year of his life, or if Ted’s wish to be cremated and scattered at sea were simply ignored. Ted Williams never met with Alcor representatives, and he never signed their Consent for Cryonic Suspension form, either. John-Henry, acting as power of attorney, signed it for Ted after his death, even though his power of attorney ended when Williams died.

The only written evidence that John-Henry ever presented to support his claim that his father had opted for cryonic freezing was an oil-stained note, handwritten in block letters, that he produced three weeks after Ted’s death. The note read:

11-2-00 JHW, Claudia and Dad all agree to be put into bio-stasis after we die. This is what we want, to be able to be together in the future, even if it is only a chance.

John-Henry Williams

Ted Williams

Claudia Williams

SOMETHING FISHY

John-Henry’s detractors were suspicious of the note. While Ted usually signed his autographs as “Ted Williams,” he always signed legal documents as “Theodore S. Williams.” They didn’t doubt it was Williams’s signature, only where it came from. Whenever he was getting ready to autograph baseball memorabilia, Ted commonly signed his name on a few blank pieces of paper to warm up. Bobby-Jo and others believe that John-Henry faked the note by writing the text onto a piece of paper that already had one of Ted’s warm-up signatures on it. But when Claudia vouched for her signature in an affidavit, the executor of the estate accepted the note as a genuine expression of Ted’s wish to be cryonically frozen.

By now Bobby-Jo had spent more than $87,000 from her own retirement fund on lawyers to have her father taken out of deep-freeze and cremated according to the instructions in his will, but with her money running out and Claudia Williams vouching for the authenticity of the note, she gave up the fight. Ted’s head and body remain frozen to this day.

Alcor billed John-Henry $136,000 for services rendered; he sent them an initial payment of $25,000 and defaulted on the rest. As of August 2003, he still hadn’t paid, though by then it wasn’t clear if there was any money left to spend. During the last years of Ted’s life, John-Henry had apparently used his power of attorney to raid his father’s assets and use them to bankroll an Internet startup company. When the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, the company filed for bankruptcy, nearly $13 million in debt. By the time Ted died, most of his assets had been sold off or mortgaged to the hilt.

THE END?

John-Henry must have worked out some kind of arrangement regarding his father’s Alcor bill, because when the younger Williams died from leukemia in 2004 at the age of 35, his body was shipped to Alcor, too. Is he floating in the same tank as his dad? They’re big enough to hold four people, but Alcor isn’t talking. The only thing that can be said for certain is that if the two men are thawed out and brought back to life, John-Henry will sure have a lot of explaining to do.

This article is reprinted with permission from The Best of the Best of Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader. They’ve stuffed the best stuff they’ve ever written into 576 glorious pages. Result: pure bathroom-reading bliss! You’re just a few clicks away from the most hilarious, head-scratching material that has made Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader an unparalleled publishing phenomenon.

This article is reprinted with permission from The Best of the Best of Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader. They’ve stuffed the best stuff they’ve ever written into 576 glorious pages. Result: pure bathroom-reading bliss! You’re just a few clicks away from the most hilarious, head-scratching material that has made Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader an unparalleled publishing phenomenon.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Boy, talk about what people will do for greed……

There’s no such word as cryonically.

@Sumfuku: Yes there is

Ted William’s head is still floating around and it smells like tuna.