Before the White House

George Washington was inaugurated as president in 1789 and John Adams was inaugurated in 1797…but the White House didn’t open its doors until 1800. So where did America’s first two presidents live?

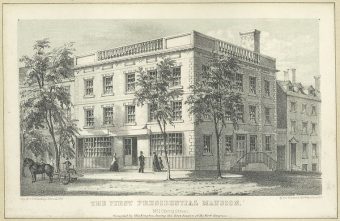

First Presidential Address: 3 Cherry Street, New York City

First Presidential Address: 3 Cherry Street, New York City

Moving In: New York served as the nation’s capital from 1789 to 1790. One week before George Washington was inaugurated on April 30, 1789, he moved into an elegant three-story brick mansion on Cherry Street, on the east side of Manhattan, that Congress rented for him at a cost of $845 per year. Washington lived there with his wife, Martha; her two grandchildren, Nelly and George Washington (“Washy”) Parke Custis; and more than 20 paid servants, indentured servants, presidential staffers, and slaves.

Moving On: As large as it was, the mansion soon proved too small for Washington’s needs—some secretaries had to sleep three to a room, and the dining room could accommodate no more than 14 people at state dinners. When Washington learned that the French ambassador, the Count de Moustier, was returning to France and was giving up the house he rented at 39–41 Broadway, he snapped up the lease and moved there in February 1790.

Aftermath: By the 1850s, the area around 3 Cherry Street had degenerated into a district of seedy taverns, brothels, and flophouses; in 1856 the house was torn down as part of a street-widening project. Then in the 1870s, the entire neighborhood was leveled to make room for the Manhattan approach to the Brooklyn Bridge. Today, the only reminder of the nation’s first presidential residence is a commemorative brass plaque on the anchorage of the bridge. Even that’s off limits to the public: After 9/11 the anchorage was fenced off for security reasons.

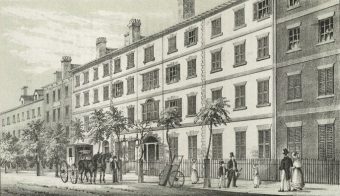

Second Presidential Address: 39–41 Broadway, New York City

Second Presidential Address: 39–41 Broadway, New York City

Moving In: This four-story mansion, located on Manhattan’s prime thoroughfare, close to Trinity Church and just north of Bowling Green, was, as one historian put it, “the finest house in the city and in the most fashionable quarter.” A visitor who saw it and several neighboring buildings in 1787 when they were being built said they were “by far the grandest buildings I ever saw.”

Washington supervised much of the interior decoration himself, filling the rooms with hundreds of pieces of furniture, fixtures, and other items that he bought from the departing Count de Moustier, and doing the rooms up in his favorite color: green. “Green was the omnipresent color of the house, which had green silk furniture and a green carpet spotted with white flowers,” biographer Ron Chernow writes. “Washington’s love of greenery was further reflected in his purchase of ninety-three glass flowerpots scattered throughout the residence.”

The house was also one of the best lit in the city: Washington had a new kind of whale-oil lamp installed that produced twelve times the light that candles did.

Moving On: Washington lived there for just six months, from February to August 1790. That July he signed the Residence Act into law, which required that the capital move to Philadelphia for ten years while the permanent Federal City, soon to be known as Washington, D.C., was being built. (See: A Capital Idea- How a Pile of Unpaid Bills Led to Washington, D.C.)

Aftermath: By the 1820s, the house at 39–41 Broadway was doing business as the swanky Mansion House Hotel. It later served as a boarding house and was eventually demolished. In 1928 a 36-story office building was built on the site. That building still stands; today it houses a pharmacy, medical offices, and other businesses.

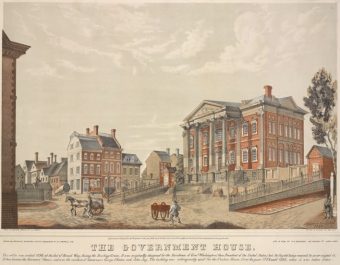

Third Presidential Address: Government House, New York City

Third Presidential Address: Government House, New York City

(Not) Moving In: In 1789, perhaps thinking it would remain the nation’s capital permanently, the New York state legislature passed a resolution to build a presidential mansion at the foot of Broadway, at Bowling Green. The mansion was built, but Washington never lived there. By the time the building was completed in the spring of 1791, the federal government had already relocated to Philadelphia.

Aftermath: At this time New York City was also the state capital, so when the federal government decamped to Philadelphia in 1790, Government House served as the official governor’s residence. Just two governors lived there before the state capital moved to Albany in 1797. The building served briefly as a boarding house and then as the Customs House for the Port of New York from 1799 until it burned down in 1814. The city sold the site at public auction the following year, and in 1892 the federal government bought it back. A new Customs House was built on the site in 1901; today the building is the home of the city’s National Museum of the American Indian.

Fourth Presidential Address: 190 High Street, Philadelphia

Fourth Presidential Address: 190 High Street, Philadelphia

Moving In: Washington moved to this location in November 1790, after the capital was relocated to Philadelphia. The 3½-story brick house was one of the largest in the city. Years earlier, when the British occupied Philadelphia during the Revolutionary War, General William Howe used it as his headquarters while Washington and his soldiers suffered through the winter at Valley Forge. After the British left the city, Benedict Arnold, whom Washington had appointed military governor of the city, used it as his headquarters. Arnold is believed to have begun his treasonous communications with the British while living in the house.

As big as the house was, Washington—who lived there with as many as 30 people at a time, including family members, servants, slaves, and aides—still found it to be too small for his purposes. Since there were no larger houses to move to, Washington stayed put and had some of the public rooms enlarged by extending them out into the gardens. (He also had the tub removed from a second-floor bathroom so that he could use the room as his private office.)

Moving On: Washington served out the remainder of his two presidential terms in the house. When he left office in March 1797, his successor, John Adams, moved in. Adams was none too impressed by the condition of the place when he took office. “The furniture belonging to the public is in the most deplorable condition,” he complained to First Lady Abigail Adams. “This house has been the scene of the most scandalous drinking and disorder among the servants that I ever heard of.” Adams and his wife lived there until the capital relocated to Washington, D.C., in 1800 and they became the first residents of the White House.

Aftermath: After the Adamses moved out, the house in Philadelphia was operated as a hotel, but that failed after just three years. The house was then converted into retail stores on the ground level and a boarding house on the upper floors. Most of the building was torn down in 1832, and what little remained was demolished in the 1950s. By then the precise location of the house had long been forgotten, and a public restroom was built on the site in 1954. Nearly 50 years passed before anyone realized that Washington and Adams had lived where people now squatted. A plaque was then installed on an exterior wall of the toilet; then in 2003 the restroom was torn down and replaced with an open-air pavilion that shows the footprint of the house and also profiles the lives of nine slaves who lived with Washington during his presidency.

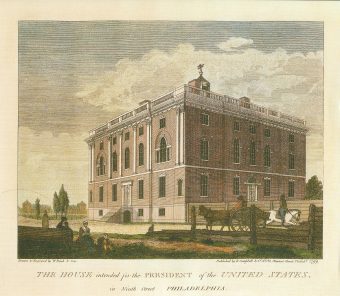

Fifth Presidential Address: 9th and Market Streets, Philadelphia

Fifth Presidential Address: 9th and Market Streets, Philadelphia

(Not) Moving In: Philadelphia’s city fathers knew that when the capital moved there from New York in 1790, the move was only temporary. But that didn’t stop them from trying to keep the federal government in the city permanently. As part of that effort, the city spent more than $110,000 constructing the “President’s House,” an enormous mansion on Ninth Street for future presidents to live in.

The building, three times the size of the house at 190 High Street and two-thirds the size of the White House being built in Washington, D.C., was nearly completed during George Washington’s presidency. But he refused to move there—and so did John Adams, even after the city doubled Adams’s rent on the High Street house. (Washington didn’t want to interfere with the move to Washington, D.C., and Adams feared he wouldn’t be able to afford such a big house on his $25,000-a-year salary. In those days presidents had to pay all their living expenses out of their own pockets.)

Aftermath: The city held on to the “President’s House” until the federal government packed up and moved to Washington, D.C., in the summer of 1800; then it threw in the towel and sold the building at public auction to the University of Pennsylvania in July 1800. The university demolished the building in 1829 and built two new ones in its place.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Canoramic Bathroom Reader. Weighing in at a whopping 544 pages, Uncle John’s CANORAMIC Bathroom Reader presents a wide-angle view of the world around us. It’s overflowing with everything that BRI fans have come to expect from this bestselling trivia series: fascinating history, silly science, and obscure origins, plus fads, blunders, wordplay, quotes, and a few surprises.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Canoramic Bathroom Reader. Weighing in at a whopping 544 pages, Uncle John’s CANORAMIC Bathroom Reader presents a wide-angle view of the world around us. It’s overflowing with everything that BRI fans have come to expect from this bestselling trivia series: fascinating history, silly science, and obscure origins, plus fads, blunders, wordplay, quotes, and a few surprises.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|