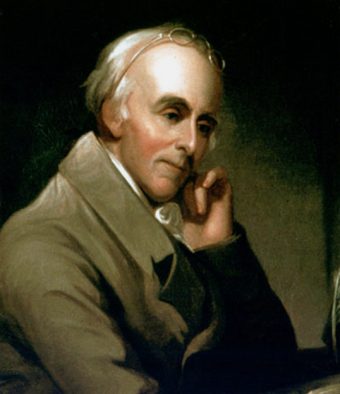

The Forgotten Founding Father, Benjamin Rush

56 men signed the Declaration of Independence in the summer of 1776. Among them were many of the most notable figures in American history, including John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin. While there are certainly names on that list that the average American wouldn’t recognize (like Stephen Hopkins, who’s less famous than his cousin Benedict Arnold), there is at least one on there that every citizen should know, but many don’t: Benjamin Rush.

56 men signed the Declaration of Independence in the summer of 1776. Among them were many of the most notable figures in American history, including John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin. While there are certainly names on that list that the average American wouldn’t recognize (like Stephen Hopkins, who’s less famous than his cousin Benedict Arnold), there is at least one on there that every citizen should know, but many don’t: Benjamin Rush.

Beyond simply signing the Declaration of Independence, Rush was a war veteran, a passionate abolitionist, an advocate of public education, a controversial but extremely significant physician, a critic of George Washington and an early proponent of considerate treatment of mental illness. Here’s the story of the forgotten founding father, Benjamin Rush.

Born on January 4, 1746 during an angina maligna epidemic in Philadelphia, Rush was the fourth of a seven child religious family. His father John was a gunsmith, but he died when Benjamin was only six. His mother, Susanna, was a well-educated country girl. When Rush’s father died, Susanna opened a grocery store to support the family. Rush would later recall that his mother’s “uncommon talents and address in doing business commanded success” led the store to become one of the largest in the city. This financial success afforded Rush the opportunity to go to private school in Maryland and the College of New Jersey (which later would become Princeton) where he became the college’s youngest graduate ever at the age of 15.

After school, he moved back to his home city, where he was a student and apprentice under several notable doctors at the College of Philadelphia, the first medical school in America. In 1766, Rush went to Edinburgh for his medical degree, where legend has it that Ben Franklin at least partially paid for this venture, as he did for many young American medical students at the time who came across the ocean. Rush returned to America two years later and was promptly awarded the professorship of chemistry at the College of Philadelphia, making him the first person to hold that position in the colonies.

It was around this time that Rush started taking a stand against slavery and the slave trade, earning the respect of many of the city’s leaders and the ire of others. Drawing on his religious upbringing and encouraged by prominent Quaker Anthony Benezet, Rush published a pamphlet entitled, “An Address to the Inhabitants of the British Settlements in America, upon Slave-Keeping.” Based on his medical background, it was a complete takedown of the entire institution of slavery.

While some of his ideas were more than a little off-base, like that black skin was due to a form of leprosy, his overarching point was that black people were medically not any different than white people, other than the color of their skin; thus, they deserved the same respect and rights afforded to any other human being. With regard to the institution of slavery, he noted,

Slavery is so foreign to the human mind, that the moral faculties, as well as those of the understanding, are debased, and rendered torpid by it.

Along with his support for other social reforms, like fair treatment of prisoners and free public education, this was all part of his belief that God had given everyone a set of natural rights. In his view, to deny any human being these rights was to go against God’s will.

Rush may have only been in his 20s when the Revolutionary spirit began to overtake the colonies, but he was already well-respected. Because of his friendship with Franklin, he was introduced to many of the colony’s leaders, including Thomas Paine. Legend has it that Rush was the one who suggested to Paine the title “Common Sense” for his now legendary pamphlet. Whether true or not, in 1775, Rush enrolled as a surgeon for the Pennsylvania Navy, where he wrote a manual about how to keep soldiers as healthy as possible. This text was used by the US military up until the Civil War.

While he wasn’t part of the first Continental Congress, he was part of the secret society Sons of Liberty (who were behind the Boston Tea Party) and was among those who greeted the delegates upon arrival in Philadelphia. Months after marrying his friend’s daughter, 16 year old Julie Stockton, he was asked to join the Continental Congress in August of 1776. While he was not there for the adoption of the Declaration of Independence in early July, Rush was there to sign it on August 2nd, his signature joining 55 others in history.

As the war with Britain dragged on, Rush knew he had to contribute to the cause. Signing on as the military hospital chief for the Middle Department (a region that consisted of his home state of Pennsylvania) of the Continental Army, he was appalled at the condition of the soldiers. Not well fed, clothed or taken care of, young men were showing up in Rush’s hospital with ailments that Rush believed to be easily preventable via competent leadership. Not only was the treatment of the soldiers inhumane in Rush’ opinion, but constant illness was bringing down the morale of the Army. Taking it to the top, Rush lodged a complaint of neglect and misadministration against his superior, Dr. William Shippen, with General George Washington himself. This didn’t turn out the way Rush hoped. Washington, in turn, sent the complaint to Congress, who cleared Shippen of any wrongdoing.

Angry that his recommendation went ignored and Washington didn’t do more, Rush wrote a supposed “anonymous” letter to Virginia governor Patrick Henry questioning Washington’s competence. Forever a Washington loyalist, Henry forwarded the letter to his friend. Despite it being anonymous, Washington recognized Rush’s handwriting. Accused of disloyalty and facing being court-martialed, Rush resigned his position.

While this more or less effectively ended his political career, it didn’t stop him from giving his opinion or pushing for social change. He continually advocated for free public education saying that “a republican nation can never be long free and happy” without its citizens being educated. Rush also pressed for better and cheaper health care, being the first to open a free clinic in the new United States. He also helped found Dickinson College, as well as the Young Ladies’ Academy of Philadelphia, the latter of which was the first higher education institution for women in Philadelphia. He also argued for the better treatment of prisoners and, in 1808, was named by President Adams to be the treasurer of the United States Mint.

While his political and social reform accomplishments were substantial, it is his post-Revolution medical career that has stood out historically, though of course due to the state of medical science in his age, his ideas today have largely been discarded and many of his efforts likely did more harm than good, unbeknownst to him. For instance, throughout the late 18th century, Philadelphia was racked with a number of yellow fever epidemics. Deadly and without a clear cure, the epidemics killed thousands with the one in 1793 being particularly bad. While Rush should be lauded for staying in the city during this time, especially when many doctors had fled, his attempts at curing yellow fever were – even at the time – considered controversial. Immense bloodletting and the administration of mercury powder were Rush’s main means of fighting yellow fever. Needless to say, they didn’t work and, in fact, some of his attempts killed people who may have otherwise survived the disease.

In 1803, Rush notably was put in charge of giving Meriwether Lewis a crash course in frontier medicine, particularly focusing on treating various maladies that the Lewis and Clark Expedition might encounter. He also provided the group with a medical kit stocked with items Rush thought they’d need.

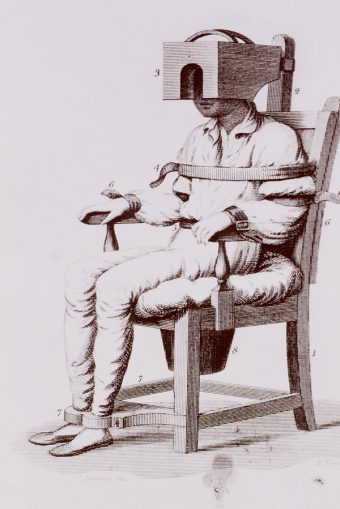

Other notable early 19th century work Rush undertook included attempting to find ways to cure those suffering from mental illness, making him among the first to believe that this should be considered a disease of the brain as opposed to something like “possession of demons.” He constructed two devices to aid in treating mental illness, with one being the “tranquilizing chair.” Believing mental illness stemmed from the inflammation of the brain, the chair and the box that was to be put on top of the patient’s head was supposed to limit blood flow to the brain. While primitive and inhumane by today’s standards, it was a far better alternative to the other methods in the colonial age, including extreme isolation and leather straps. Slightly more helpfully, Rush also advocated patients regularly perform various relaxing activities like gardening, sewing, exercising, listening to music, etc. For his pioneering work in the field of mental health, Rush is known today as the “father of American psychiatry.”

Other notable early 19th century work Rush undertook included attempting to find ways to cure those suffering from mental illness, making him among the first to believe that this should be considered a disease of the brain as opposed to something like “possession of demons.” He constructed two devices to aid in treating mental illness, with one being the “tranquilizing chair.” Believing mental illness stemmed from the inflammation of the brain, the chair and the box that was to be put on top of the patient’s head was supposed to limit blood flow to the brain. While primitive and inhumane by today’s standards, it was a far better alternative to the other methods in the colonial age, including extreme isolation and leather straps. Slightly more helpfully, Rush also advocated patients regularly perform various relaxing activities like gardening, sewing, exercising, listening to music, etc. For his pioneering work in the field of mental health, Rush is known today as the “father of American psychiatry.”

In the fall of 1813, Rush contracted typhus fever while attempting to help during an epidemic and died shortly thereafter at the age of 67. Despite his controversial political and medical career, he was hailed as a Philadelphia icon when the news of his death spread. Benjamin Rush is buried at Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia, close to his good friend Ben Franklin.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Large Number of Human Remains Found In Ben Franklin’s Basement

- Why Elections Are Held on Tuesday in the United States

- The Truth About Ben Franklin’s Epigrams

- The Origin of the American Democratic Party

- The Origin of the Republican Party

| Share the Knowledge! |

|