From Sorcerer to Clergyman to Pirate to Admiral, the Remarkable Life of Eustace The Monk

At the turn of the 13th century, Eustace Busket fought, raided, killed, embezzled, betrayed, revenged, impersonated and prayed his way across France, Spain and England. Although better known as Eustace the Monk, this younger son of a county lord spent little time in a monastery, choosing instead to live the life of a steward, mercenary and pirate.

At the turn of the 13th century, Eustace Busket fought, raided, killed, embezzled, betrayed, revenged, impersonated and prayed his way across France, Spain and England. Although better known as Eustace the Monk, this younger son of a county lord spent little time in a monastery, choosing instead to live the life of a steward, mercenary and pirate.

Born in 1170 near Boulogne, France, Eustace’s story really begins in Toledo, Spain where he is rumored to have studied black magic and, according to the contemporary work Histoire des Ducs de Normandie, “No one would believe the marvels he accomplished, nor those which happened to him many times.” Ultimately giving up his parlor tricks, he soon decided to join the Benedictine monastery at St. Samer Abbey (near Calais).

At some point around 1190, Eustace’s father was murdered, and Eustace left the Benedictines to seek revenge against Hainfrois de Heresinghen, the supposed killer. Agreeing to duel through surrogates, Heresinghen’s champion won, and, thus, the trial by combat acquitted Heresinghen of the charges.

With his failed revenge, and now preferring life outside of the monastery, Eustace next went to work for Count Renaud de Dammartin of Boulogne as his seneschal (steward), peer and bailiff. Most important for the future life of Eustace, his duties included oversight of the Count’s property. After Heresinghen instituted a plot to discredit him, the Count asked for an accounting and Eustace fled into the Forest of Boulonnais, circa 1204. Taking his flight as a sign of guilt, the Count seized Eustace’s property and burned his land. Not one to take such a slight lying down, Eustace then launched a series of raids against the Count’s property, including burning down two mills that the Count had recently built. Whether or not he was really guilty of embezzling, as the Count came to believe, after destroying the Count’s property, he was officially an outlaw, and one with a very powerful enemy.

Having at this point been a supposed sorcerer, a monk, and an administrator, Eustace decided to take up a new career- piracy. Sailing in the English Channel and the Strait of Dover, Eustace sometimes worked for himself and at other times as a mercenary between 1205 and 1212. Making something of a name for himself, together with his brothers, Eustace ultimately commanded as many as 30 ships under the flag of King John of England. Raiding along the coast of Normandy and the Channel Islands, he and his brothers established several bases on the islands, including the Castle Cornet in Guernsey.

Not satisfied with the tremendous spoils he’d accumulated thus far, around 1212, Eustace began playing both sides, raiding along the English coast as well; at this same time, the Count de Dammartin struck an alliance with King John. Officially switching sides at this point, Eustace took his skills back to France, where he found work with Prince Louis. Together, they supported the English rebellion in 1215-1216 (when King John refused to honor the negotiations that culminated in the Magna Carta) with the idea that Louis would eventually take the English throne.

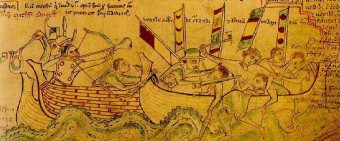

King John died, however, and with the rise of Henry III, the rebellion lost support. Undeterred, in August 1217, France sent its fleet across the Channel, led by Robert de Courtenai with Eustace as admiral of its 70-plus ships, some of which were heavily overloaded, bearing weapons, men and horses.

The English were prepared and met the French fleet at Sandwich. Seizing control of the fleet from Eustace, de Courtenai ordered the ships into an ill-advised attack; losing the wind, the French fleet suffered serious losses, due in no small part to the English releasing lime into the wind, which blinded the French troops.

Eventually, de Courtenai and the knights were taken for ransom, and the regular soldiers were slaughtered.

As for Eustace, he was found hiding in the bilge of his ship. As with the other notables captured in the battle, he offered to pay a fortune in ransom for his release, but the irritated English, whom Eustace had betrayed only a few years before, decided not to take the money in his case. Instead, they tied him down and had a man by the name of Stephen Crabbe lop off his head. In the (largely fictional) 1284 work covering Eustace’ life, The Romance of Eustace the Monk, it concluded of his death (translated), “No man can live long who spends his days doing ill.”

In the aftermath, Louis ultimately relinquished his claim to the throne of England, and Eustace’s brothers were dispossessed of their Channel Islands lands.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Did People in Columbus’ Time Really Think the World was Flat?

- Parrots, Peg-legs, Plunder – Debunking Pirate Myths

- The Female Prostitute That Rose to Become One of the Most Powerful Pirates in History and Whose Armada Took on the Chinese, British, and Portuguese Navies… and Won

- That Time Julius Caesar was Kidnapped by Pirates

- The Origin of “Port” and “Starboard”

Bonus Fact:

- The Magna Carta (Great Charter) was executed at Runnymede on June 15, 1215 between King John and his supporters, including Stephen Langton, the Archbishop of Cantebury and William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, and the rebel barons including Richard de Clare, Earl of Hertford and Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of Essex and Gloucester. In a nutshell, the charter was born of King John’s terrible governance. Seeing himself as above the law, John was arbitrary and brutal, and during the 10 years preceding the negotiations at Runnymede, John bled the English barons dry with high taxes he used to pay for disastrous military campaigns in France. Upset, the barons eventually got John to agree to certain reforms, which included access to justice and a trial by peers, limits on taxes and the Crown’s ability to seize property, and protection from illegal imprisonment. Although bare-bones by today’s standard, the Magna Carta is considered the turning point in the quest for civil liberties and the rights of free men against the state.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|