Life in a Jar- Sendler’s List

One amazing woman in Poland—and four teens in Kansas who tracked her down and told her story.

One amazing woman in Poland—and four teens in Kansas who tracked her down and told her story.

SENDLER’S LIST

In 1999 a teacher at Uniontown High School in Kansas encouraged four students to do a project for a national History Day contest. Norm Conard told his 9th-grade students—Elizabeth Cambers, Megan Stewart, and Janice Underwood, and 11th-grader Sabrina Coons—that the project should reflect the classroom motto, “He who changes one person, changes the world entire.” The quote is from the Jewish holy book the Talmud, and Conard suggested basing the project on the Holocaust.

He showed them a 1994 news clipping about “other Schindlers,” people who, like Oskar Schindler (made famous in the film Schindler’s List), had saved Jews from the Nazis during World War II. One of the people mentioned was a Polish woman named Irena Sendler, who was said to have saved 2,500 Jewish children from the Warsaw ghetto. Schindler had saved about 1,100 people. “We thought this had to be a mistake or something,” said Conard. “Maybe this Sendler saved 250, but not 2,500. I mean, nobody had ever heard of this woman.”

SEARCHING FOR IRENA

“We became obsessed with finding out everything we could about Irena,” said 15-year-old Elizabeth Cambers. And they soon found out that the number was right. But how Irena Sendler had saved the children was almost unbelievable.

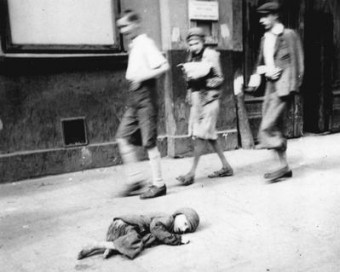

Sendler was a social worker in Warsaw when the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939. By 1940 they had created the Warsaw ghetto: 400,000 Jews were confined to an area one square mile in size. They were not allowed to leave, and conditions quickly became deplorable. Hundreds died every day from starvation or disease, and soon more were being sent to die in death camps. By 1942 more than 80,000 had perished.

Sendler, who was not Jewish, was sickened by what she saw…so she made a plan. She forged a pass from the Warsaw Epidemic Control Department and, starting in 1942, went into the ghetto every day. There she would ask parents to do the unthinkable: give their children to her so she could smuggle them out. It meant that the parents would probably never see them again, but for the children to stay, the stricken parents knew, was to let them die.

BURYING HOPE

At incredible risk to herself, Irena smuggled dozens of children out of the ghetto day after day. She took them right past the guards, showing fake documents and saying they were ill. Or she would put children in coffins, saying they were dead. Once out, she gave the children phony papers with new names and found Polish families to adopt them, or she placed them in orphanages. Some she hid in churches and convents.

At incredible risk to herself, Irena smuggled dozens of children out of the ghetto day after day. She took them right past the guards, showing fake documents and saying they were ill. Or she would put children in coffins, saying they were dead. Once out, she gave the children phony papers with new names and found Polish families to adopt them, or she placed them in orphanages. Some she hid in churches and convents.

But while she was saving the children, Sendler knew that she was taking them from their families, and from their own identities. So she made lists of all their real names and addresses and their new locations—in code—and put the lists into glass jars. Then she buried the jars beneath an apple tree in a neighbor’s backyard, hoping that one day she could dig them up, find the children, and reunite them with their families.

On October 20, 1943, Irena Sendler was found out by the Nazis. She was imprisoned—and, because she was the only one who knew the location of the children and the jars, she was tortured. Gestapo agents broke both her feet and both her legs, but Sendler refused to tell them anything. She spent three months in prison, then was sentenced to death.

The girls were so moved by Sendler’s story that they wrote a play about it entitled Life in a Jar. Elizabeth Cambers played “Jolanta,” Irena’s code name and the only name by which the children knew her, and Megan Stewart played a mother who must give up her children. They performed the play at school, then in local clubs and churches. People in the community were so moved by Sendler’s story that the school district, which didn’t have a single Jewish student, declared an official Irena Sendler Day. On top of that, the girls’ work won them first prize in the National History Day contest for the state of Kansas. But the best was yet to come.

FINDING IRENA

The girls kept looking for more clues about Irena’s life. They contacted the Jewish Foundation for the Righteous, an organization that honors non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust, to ask if they knew the location of Irena’s grave. They didn’t, they said, but they had something else: her address. Irena Sendler was alive.

Elizabeth, Megan, Janice, and Sabrina immediately wrote to Irena in Warsaw and told her about their project and play. Six weeks later they got an enthusiastic reply. “Your performance and work,” Irena wrote, “is continuing the effort I started over fifty years ago.”

Sendler also told them the rest of her story: She had been brutally tortured and sentenced to death by the Nazis when she refused to tell them where the children were. But the Polish underground came to her rescue, securing Irena’s release by bribing a guard. She spent the rest of the war a fugitive.

After the war ended, Sendler immediately went back to her neighbor’s house, dug up the jars, and began tracking down the children, hoping to reunite as many as possible with their parents. She was able to find many, but hundreds she could not—and most of the parents were dead.

WARSAW

In 2001 the students’ dream came true when they traveled to Poland to meet the subject of their long study. Irena Sendler, by then 89 years old, took the girls in like granddaughters. “We ran up and hugged her and cried,” said Elizabeth Cambers. “We told her she is our hero, but she said she doesn’t think of herself that way. ‘Heroes do extraordinary things,’ she told us. She just did what she had to do.”

In 2001 the students’ dream came true when they traveled to Poland to meet the subject of their long study. Irena Sendler, by then 89 years old, took the girls in like granddaughters. “We ran up and hugged her and cried,” said Elizabeth Cambers. “We told her she is our hero, but she said she doesn’t think of herself that way. ‘Heroes do extraordinary things,’ she told us. She just did what she had to do.”

The group was even able to meet some of the children, now in their 50s, who were saved by Irena (and by others who helped her, Irena was always quick to point out). One was Elzbieta Ficowska, rescued by Irena when she was five months old by being carried out in a carpenter’s toolbox. They also met a Polish poet who was saved by Irena, who called the young women “rescuers of the rescuer” for bringing Irena’s amazing story to the public. And to the public it went. The story of the students’ visit to Irena in Warsaw and of their performance of Life in a Jar spread. When they returned home, the four young women were interviewed on radio and TV, and in newspapers and magazines worldwide.

The four original students have all graduated, but the Sendler Project, as it is now known, continues today with Mr. Conard and new students. Life in a Jar has been performed more than 170 times in the United States and Europe. They also have a website, through which they raise money for people like Sendler, who risked their lives to save others.

Irena Sendler continued to correspond with the four girls (they visited her twice more, the last time in 2005). In the years before her death, she lived in a nursing home in Warsaw and was cared for, appropriately, by a woman she smuggled out of the Warsaw ghetto more than 60 years before. Sendler died on May 12, 2008 at the age of 98.

This article is reprinted with permission from The Best of the Best of Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader. They’ve stuffed the best stuff they’ve ever written into 576 glorious pages. Result: pure bathroom-reading bliss! You’re just a few clicks away from the most hilarious, head-scratching material that has made Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader an unparalleled publishing phenomenon.

This article is reprinted with permission from The Best of the Best of Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader. They’ve stuffed the best stuff they’ve ever written into 576 glorious pages. Result: pure bathroom-reading bliss! You’re just a few clicks away from the most hilarious, head-scratching material that has made Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader an unparalleled publishing phenomenon.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

You also have Aristides de Sousa Mendes, portuguese council, who saved over 30.000 lives during world war 2, and acted agains the orders of our former prime minister, Salazar:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristides_de_Sousa_Mendes

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/sousa-mendes-saved-more-lives-than-schindler-so-why-isnt-he-a-household-name-too-2105882.html