The Story of the Monkees

In 1966 the best-selling rock band in the United States wasn’t the Beatles—it was the Monkees. And they weren’t even a “real” band (at least at first); they were a Hollywood creation.

In 1953 a TV producer named Bob Rafelson was traveling through Mexico with a group of “four unruly and chaotic folk musicians” and thought their exploits would make for a fun TV show. He unsuccessfully pitched the idea to Universal in 1960. Five years later, Rafelson was working at Screen Gems, the TV division of Columbia Pictures, with another young producer, Bert Schneider. Both were fans of the Beatles’ film A Hard Day’s Night and marveled at how it had fused comedy and rock music. They wondered: Could that be translated to TV?

The two men formed Raybert Productions and began developing their series. At first, they wanted to hire an established band, such as Herman’s Hermits, but decided they didn’t want to deal with record company contracts. But through the magic of TV, the band didn’t even need to be musicians—they wouldn’t really be playing the instruments; they only had to look convincing. Acting experience wouldn’t be necessary, either.

In 1965 they ran this ad in Hollywood Reporter and Variety: “MADNESS!! AUDITIONS. Folk & Roll Musicians, Singers for acting roles in new TV series. Running parts for 4 insane boys, age 17–21.”

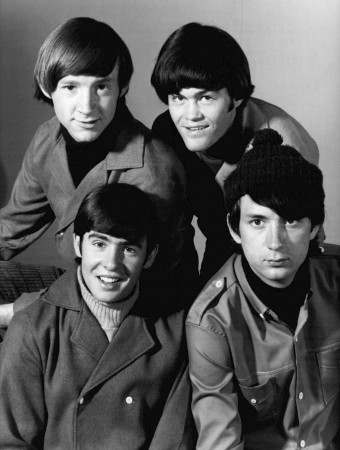

MICKY, DAVY, PETER, AND MIKE

Word spread around the L.A. music scene, and 437 “folk & roll musicians” and “insane boys” showed up to audition. After a three-month process in which the leading candidates were called back several times to perform in various groupings to see who had chemistry together, Raybert ended up with two professional actors and two professional musicians—all of whom could sing and all of whom were funny.

- Micky Dolenz, 21, a former child star (he’d starred as an orphaned acrobat on the 1956 show Circus Boy), was hired to be the drummer, even though he couldn’t play the drums or even look like he could. His singing, however, was top-notch, so he ended up singing on most of the Monkees’ hits.

- Davy Jones, 21, was an experienced stage performer who had toured with the musical Oliver! in 1962. (With that production, he had appeared on the same 1964 Ed Sullivan Show as the Beatles, had seen the girls going hysterical, and said to himself, “I want a bit of this.”) Jones was under contract with Screen Gems and was urged to audition—he could sing, was good-looking, and had a British accent—in other words, he was Beatles-esque. He was hired as the “official” lead singer.

- Stephen Stills of the band Buffalo Fish (later Buffalo Springfield) was cast, but he backed out when he learned that Screen Gems would own the rights to any songs he wrote. He suggested an ex-bandmate named Peter Tork, 24. By the time Rafelson tracked him down, Tork was working as a dishwasher. He was primarily a guitarist; in this band, he’d be the bassist.

- Mike Nesmith, 21, was playing in a band called the Survivors. Already a successful songwriter—he’d written Frankie Laine’s “Pretty Little Princess”—he was on his way to a successful music career when he auditioned for the show. Wearing his trademark wool cap and carrying a sack of laundry, Nesmith announced in his slight Texas drawl, “I hope this ain’t gonna take too long, fellas, ’cause I’m in a hurry.” He was named lead guitarist.

HEY, HEY, WE’RE THE CREEPS!

Raybert had their four musicians, but they were lacking one important detail—a name for the band. Some possibilities tossed around: the Creeps, the Turtles, and the Inevitables. Then Schneider suggested taking a cue from how the Beatles had misspelled “beetles,” and he turned “monkeys” into Monkees.

Rafelson and Schneider now needed money to film a pilot. Former child star Jackie Cooper, then a Screen Gems executive, offered $250,000 before he even saw the script. It helped that Schneider’s father was the president of Columbia Pictures, parent company of Screen Gems.

In early 1966, Rafelson and Schneider hired character actor James Frawley to conduct acting classes and direct the pilot. It would be his first directing job. They told him to relax and to “dare to be wrong.” So Frawley had the band members, who were quite stiff at first, watch Marx Brothers movies and perform improv exercises: “Swim around in slow motion! Now roll around on the floor! Now you’re a crab! Now you’re giraffes! Run around and talk like a giraffe would talk!” By the time they filmed the pilot in the spring, the Monkees’ personas were in place and, perhaps more importantly, they’d become friends.

TEST PILOT

The plot of the pilot: The band’s upcoming gig at a fancy country club is in jeopardy when the sweet-16 birthday girl falls for Davy, and her stuffed shirt of a father doesn’t approve. The four stars—even Dolenz and Jones, who’d done some TV—were overwhelmed by the complexities of the shoot. Raybert wanted a fast show, so they brought in TV commercial production teams, who filmed the stars riding on motorized skateboards, running amok through hotels, and doing other silly things. The Monkees themselves were quite lost; the show, they were told, would be crafted later in the editing booth. “The narrative of the shows was never that important,” recalls Nesmith. “What was important was a kind of kinetic energy.”

Rafelson and Schneider loved the pilot, but test audiences hated it. Tork explained why: “When the audience didn’t know who these kids were, the obnoxiousness was overpowering. They were like, ‘What are these brats doing?’” But instead of making the Monkees more polite, Raybert simply showed the pilot again—this time with early screen tests from Jones and Nesmith tacked on at the end. That did the trick: “It gave the next audience enough identification with the kids that they forgave them for being obnoxious.”

Raybert showed the pilot to NBC’s programming chief Mort Werner. “I don’t know what the hell we’ve just seen,” he exclaimed, “but I think we should put it on the air.”

MONDAY NIGHT MADNESS

The Monkees premiered on Monday, September 12, 1966, at 7:30 p.m. The show was an instant hit and ruled that time slot for two seasons. At the time, it seemed revolutionary.

Some of the cutting-edge aspects:

- Quick takes. Most shows at the time had about 15 scenes per episode. The Monkees averaged about 60.

- Surrealism. The Monkees regularly featured dream sequences, visual gags (such as “stars” in Davy’s eyes), wacky sound effects, rapid-fire scene transitions, and action that was sped up and slowed down.

- Breaking the “fourth wall.” For example, when the boys find themselves in a tough situation, Micky looks at the camera and says, “Who wrote this?” The camera follows him as he leaves the set and walks into a smoke-filled room with old Asian men crouched around typewriters.

- Music videos. Elvis and the Beatles had done it on film, but until The Monkees, no TV sitcom routinely stopped telling its story—twice per episode—to feature a music video of the band’s latest song. The Monkees’ musical interludes proved that television could sell records.

- Counterculture presented in a good light. The Monkees had long hair and lived in a groovy beach house, but compared to real hippies (or the Beatles), they were square: on-screen, they didn’t do drugs, didn’t talk politics, and didn’t disrespect young ladies. Ironically, that lack of an edge may have boosted the counterculture movement. “Kids could show their parents that there were long-haired people who weren’t deviant,” said Tork later.

The Monkees became overnight sensations…but they’d soon suffer the scorn of the music industry.

MONKEE FACTORY

On the set of The Monkees, the on-screen action was wacky and loose. But behind the scenes, NBC and Screen Gems had put so much into promoting the show that nothing was left to chance. During filming, any cast members who weren’t in the scene being shot were kept in a room with black walls and a meat-locker door. They could be loud, smoke pot, and even entertain women without being seen. Each Monkee had a corner, and in each corner a light was installed. When a Monkee’s light started blinking, that Monkee or Monkees would report to the set and perform. Then it was back to the black box.

During press interviews, they were given a list of topics they could not talk about, including politics, Vietnam, and drugs. “We were hired actors,” said Nesmith. “We came in at seven in the morning and did what we were told until seven at night. We had almost no part in the creative process.” And they often had to add vocals to their songs in recording sessions that went long after midnight.

DAYDREAM DECEIVERS

Screen Gems’ head of music, Don Kirshner, was hired to develop the band’s sound into something catchy and marketable. Kirshner tapped top songwriters of the day, including Neil Diamond, Tommy Boyce, Bobby Hart, and Carole King, who contributed to the band’s hits, such as “Last Train to Clarksville,” “I’m a Believer,” and “Daydream Believer.” Although Tork and Nesmith were both skilled guitarists and Jones was a decent drummer, the “band” wasn’t allowed to play instruments on their first two albums, The Monkees and More of the Monkees.

As the first season came to a close, word had leaked out that the Monkees were a fabricated band, but their popularity had already skyrocketed—especially that of Davy Jones, who became a teen heartthrob. To capitalize on their fame, NBC sent them on a concert tour in early 1967 to perform their hits—which they hadn’t even played in the first place. TV’s first manufactured band was about to become a real band, and the task was daunting. “Putting us on tour was like making the cast of Star Trek fight real aliens,” said Dolenz.

STEPPING STONES

The Monkees’ early concerts didn’t go well musically, but few noticed because their teenage fans didn’t stop screaming long enough to even hear them. Jimi Hendrix got the job of being their opening act, against his wishes (his manager made him do it). “Jimi would amble out onto the stage,” recalled Dolenz, “fire up the amps, and break into ‘Purple Haze,’ and the kids would drown him out with ‘We want Daaavy!’ God, was it embarrassing.” Hendrix quit after seven shows.

The Monkees soon learned to actually play together, and got a big boost on the European leg of their ‘67 tour when the Beatles threw them a lavish party. John Lennon didn’t see them as competitors or imitators, but contemporaries. He called the Monkees “the Marx Brothers of rock.”

Meanwhile, back in the States, tension mounted between the Monkees and Kirshner, especially after he rejected songs Nesmith had written…because they weren’t “Monkee enough.” The final straw came when Kirshner released a Monkees song—the Neil Diamond-penned “A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You”—without Screen Gems’ or the Monkees’ approval. Nesmith was so angry that he punched a hole in the wall of Rafelson’s office. Kirshner was fired, which gave the group more control over their music but not over their image…or even their lives.

OF MONKEES AND MEN

By this time, the Monkees were widely resented by musicians who’d paid their dues for years, only to be upstaged by a fabricated band. Not even the 1967 album Headquarters, which the Monkees wrote and performed themselves, could save their reputations. Even when the Monkees were honored, they were dissed. After season one, the show won an Emmy for Outstanding Comedy and another for Jim Frawley’s directing. In his acceptance speech, Frawley said, “I couldn’t have done this without four very special guys—Harpo, Chico, Groucho, and Zeppo.” The band took his remarks as a snub, not a compliment.

As the second season dragged on, the Monkees spent most of their waking hours working, and grew increasingly tired and jaded. How many episodes could be written about country clubs or haunted mansions the band gets lost in? The band agreed to come back for a third season only if the show switched formats to a variety program. (They got a taste of that toward the end of the second season when Frank Zappa, dressed up like Mike Nesmith, interviewed Mike Nesmith, who was dressed up like Frank Zappa.) NBC didn’t want to change the format, so they canceled The Monkees in 1968 but signed a deal with them to make three specials a year.

HEADING TO THE BIG SCREEN

The Monkees as a band, however, remained intact. In the summer of 1968, Raybert began filming a Monkees feature film conceived of by their friend Jack Nicholson while he was tripping on LSD. Head was a stream-of-consciousness, psychedelic diatribe against Hollywood—TV in particular. It began with the Monkees chanting, not singing, a parody of their theme song: “Hey, hey, we are the Monkees, you know we love to please / A manufactured image, with no philosophies.” It only got weirder from there—and it confused its teeny-bopper audience. The film was panned and made only a fraction of its budget, squashing any plans for a sequel.

The band then made a few guest appearances on TV variety shows in 1969. Their last hurrah was a bizarre NBC special, 33 1/3 Revolutions Per Monkee. In one scene, the guys were placed inside giant test tubes, a reference to being “grown in a lab.” Later, Little Richard, Fats Domino, and Jerry Lee Lewis all played pianos stacked on top of each other. The program got such poor ratings (it had run opposite the Academy Awards) that NBC canceled the remaining contracted Monkees specials. Then, citing exhaustion, Tork quit the band. The special was the last time all four Monkees would appear together for 16 years.

THE SECOND COMING…AND GOING

Throughout the 1970s, Micky Dolenz, Mike Nesmith, and Davy Jones continued performing together occasionally while also pursuing solo careers. However, the money they had made from their TV series and album sales was poorly handled, so Jones and Tork ended up deep in debt. Nesmith never had to worry about money thanks to his mother’s invention—Liquid Paper. In 1979 he inherited $25 million (about $82 million today).

While the Monkees’ success on vinyl faded, the popularity of their old TV show stayed strong. From 1969 to 1972, CBS aired reruns on Saturday mornings, and local stations aired it here and there. Then in 1986, MTV began airing the show, and it was a huge hit all over again. Now in their 40s, the Monkees reunited and recorded a new album, Justus, and followed it with a successful world tour.

Everything was rosy until the Monkees failed to show up at an MTV-thrown Super Bowl party in 1987. Though the band had missed the date because of a scheduling snafu by their manager, MTV execs saw it as an ungrateful snub and retaliated by banning the band’s videos and reruns. Monkeemania 2.0 quickly died.

THE REFAB PREFAB FOUR

While the band was still selling out stadiums around the world back in 1986, Screen Gems producer Steve Blauner thought that the Monkees revival could give way to a totally new incarnation of the band, with new members, and to reflect the music and sensibilities of the 1980s.

Following a casting process like the one conducted 20 years earlier, Blauner found four young musicians and cast them in The New Monkees, which began airing in fall 1987.

Don’t remember it? That’s because it lasted only 12 episodes, it generated no hit songs, and the four guys never went on to much else.

Another New Monkees attempt was made in 2003 by American Idol creator and Spice Girls mastermind Simon Fuller. He hired Simpsons writers Bill Oakley and Josh Weinstein to write scripts. NBC passed.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader Tunes Into TV. Here comes your wacky neighbor Uncle John to present TV the way only he can. From test patterns to Top Chef, from My Three Sons to Mad Men, as well as TV news, advertising, scandals, sitcoms, dramas, reality shows, and yadda yadda yadda, Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader Tunes into TV is “dy-no-mite!”

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader Tunes Into TV. Here comes your wacky neighbor Uncle John to present TV the way only he can. From test patterns to Top Chef, from My Three Sons to Mad Men, as well as TV news, advertising, scandals, sitcoms, dramas, reality shows, and yadda yadda yadda, Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader Tunes into TV is “dy-no-mite!”

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

This article is written in a juvenile manner, and aside from having several factual errors it also diminishes the accomplishments of the Monkees.

The story of the Monkees is really quite amazing. Kind of like the Beatles, it’s hard to believe it all really happened! It fizzled out in such a strange way in the late 60’s with Head and the bizarre 33 1/3 Revolutions show, so I’m glad the guys got back on top in the 80’s.

They were sort of the first manufactured “boy” band, except that they chose really talented guys with an independent streak, who really cared about integrity. Probably to the detriment of their bank accounts.

It didn’t hurt to have all those brilliant songwriters either, plus a multi-talented group, and a subversive tv show in the right time at the right place to help promote the records.