Abraham Lincoln and His Patent

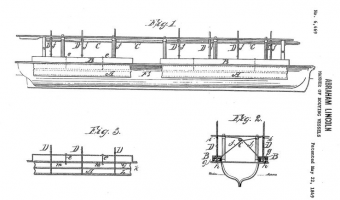

The first paragraph of US patent 6469 reveals nothing that would give the reader any thought to the future greatness of the inventor. The patent is for an improvement to help boats pass over sandbars by adding “adjustable buoyant air chambers” to the bottom of the boat. Though uncomplicated and rather simplified, the patent seems like it was written by a ship merchant or an engineer – not a lawyer and politician who would become the President of the United States. On March 10, 1849, 12 years before he was elected US Commander-in-Chief, Abraham Lincoln submitted this patent, which he called “Buoying Vessels Over Shoals,” with the design and idea for the invention having its roots in his voyages as a young man along the Mississippi River. He’s the only US President to ever submit a patent.

The first paragraph of US patent 6469 reveals nothing that would give the reader any thought to the future greatness of the inventor. The patent is for an improvement to help boats pass over sandbars by adding “adjustable buoyant air chambers” to the bottom of the boat. Though uncomplicated and rather simplified, the patent seems like it was written by a ship merchant or an engineer – not a lawyer and politician who would become the President of the United States. On March 10, 1849, 12 years before he was elected US Commander-in-Chief, Abraham Lincoln submitted this patent, which he called “Buoying Vessels Over Shoals,” with the design and idea for the invention having its roots in his voyages as a young man along the Mississippi River. He’s the only US President to ever submit a patent.

In 1828, at the age of 19, Lincoln was offered a job by a wealthy Indiana landowner, James Gentry, to help take a flatboat full of produce and cured meat along the Mississippi to New Orleans. At eight dollars a month (a little under $200 today), it certainly wasn’t a high-paying job, but it did give the teen a chance for an adventure. Prior to his trip, he had spent his entire life on farms and homesteads in Kentucky, Illinois and Indiana, knowing nothing of life beyond those borders. Gentry offered him the job simply due to happenstance. He owned a store, of which the Lincoln family were patrons. Knowing that Abe was close to the same age as his own son, Allen – who was to captain the boat, and capable of the tasks needed to be done, Gentry asked Abe.

While, very unfortunately, neither Gentry nor Lincoln took notes or kept a diary during the trip, there are a few known events that happened during the voyage. For one, the small flatboat had a real problem with sandbars. When in shallow waters and weighed down by its cargo, the ship often got stuck, which meant cargo had to be unloaded to make it lighter and the craft pushed out and then re-loaded. This was a tedious, hard, time-sucking and a potentially dangerous task.

Another thing that’s known is that the ship was attacked near Baton Rouge by a group that could be best described as river pirates. Looking for cargo and money, the ship was nearly overtaken by this group of men who had the intent of robbing and, perhaps, killing Lincoln and his companion if need be. Gentry and Lincoln were able to fight them off long enough to cut anchor and barely escape.

The last specific detail known from this trip is the stuff of legend. Years later, Allen Gentry would continue telling this story, stating that Lincoln’s future as the “Great Emancipator” was sown on that trip South. According to Gentry, upon landing in New Orleans, Lincoln saw the notorious slave markets of the city and was disgusted. Supposedly he said to Gentry at the time, “Allen, this is a disgrace. If I ever get a lick at this thing, I’ll hit it hard.” Whether he actually said those specific words as Gentry claimed, 35 years later, he did exactly that – issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed slaves from all Southern territories.

Three years later, in 1831, Lincoln journeyed along the Mississippi again while experiencing many of the same things he did the first time. In fact, it seems the issue with sandbars became even more pronounced, with written records stating that Lincoln and his crew lost time and cargo dealing with the matter of the ship being stuck on a sandbar.

There’s a prophetic story from even before leaving Illinois in 1831, with the ship getting stuck along the Sangamon River on a dam and taking on water. Lincoln rushed to the nearby cooper shop (a place where wooden barrels & casks were made), got an auger, drilled a hole in the side of the ship and proceeded to let the water run out. Then, he pushed the ship by himself off the dam. A year later, when running for the Illinois General Assembly from Sangamon County, one of his key platform points was improving the navigation of the river to bring more trade to the county. Said Lincoln in a 1832 speech, “I believe the improvement of the Sangamon River, to be vastly important and highly desirable to the people of this county.”

While he was defeated in his 1832 run for political office, Lincoln was ultimately successful two years later when he was elected to the Illinois General Assembly. While he didn’t achieve much in regards to improving the navigation of the river while in the General Assembly, this issue still nagged him. After two years there, he moved on to the Illinois House of Representative and then into the US Capitol as a Congressman in 1847. Constantly traveling the Sangamon River and often getting stuck, this finally pushed him to do something about it. Working on the patent in between Congressional sessions, he finally completed and submitted it days after finishing out his term as Congressmen.

Submitted on March 10, 1849, it revealed his interest and knowledge in better water transportation. As a lawyer, he understood that patents allowed for certain protections in terms of intellectual property. In fact, ten years later, he delivered a speech in which he championed patents by saying they are the “fuel of interest to the fire of genius, in the discovery and production of new and useful things.” He also understood that, at the time, patents needed to be accompanied by a model. Working with a Springfield mechanic, he whittled a model of a ship with his buoying device.

Said his law partner at the time, “Occasionally he would bring the model in the office, and while whittling on it would descant on its merits and the revolution it was destined to work in steamboat navigation. Although I regarded the thing as impracticable I said nothing, probably out of respect for Lincoln’s well-known reputation as a boatman.”

Today, that model and patent application is at the National Museum of American History, but there’s some dispute over exactly what the Museum has in its collection. While a curator told Smithsonian Magazine in 2006 that the model is “one of the half dozen or so most valuable things in our collection,” it is possible that what they have is in fact a replica. The nameplate on top of the model reads “Abram Lincoln,” a misspelling that has led some to believe that it’s a fake because Lincoln would have never misspelled his own name. It is also possible that the plate was added after Lincoln submitted it, but that may never be known – while his signature could be on the model, it is buried underneath centuries-old varnish. As for the patent itself, there’s little doubt that this is authentic and in the hand-writing of Lincoln. But there’s one crucial part missing – his signature, which was likely cut out and taken by a collector who had access to the patent in the 19th century.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- When Lincoln Was Almost Assassinated Nine Months Before He was Assassinated

- The Little Girl Responsible for Lincoln’s Beard

- The Secret Message Hidden in Abraham Lincoln’s Pocket Watch

- Abraham Lincoln Established the Secret Service on the Day He was Shot by John Wilkes Booth

- What Ever Happened to Confederate President Jefferson Davis?

Bonus Fact:

- The 30th Vice President of the United States, Charles Gates Dawes, won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1925 and was a self-taught pianist and composer who composed the 1912 hit song, “Melody in A Major,” which was eventually used in Tommy Edwards’ 1958 #1 hit (for a then record six weeks) “It’s All in the Game.” It has since become a pop standard, having been performed and covered by artists like The Four Tops, Isaac Hayes, Van Morrison, Elton John, the Osmonds, and Barry Manilow. More here: 5 Fascinating Vice-Presidents You’ve Probably Never Heard Of

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

For what it’s worth, my great-great Aunt was a friend of Lincoln (he proposed to her, but she turned him down because he was so homely). She wrote that he had an odd habit of calling himself Abram, referring to Abram/Abraham of the Bible, indicating he didn’t believe his revelation had yet to happened (Abram’s name was changed to Abraham after God spoke to him). Can’t imagine he’d write it on a legal document, but he was, as my gga wrote in her letters, an odd man.

That is very strange. Considering what’s happened