The Trials and Tribulations of 1904 Olympic Marathon Runners

When the United States hosted the Olympics for the first time in 1904, the games had yet to reach the high level of competition and popularity we know today. Although athletes from countries around the world were invited to participate, the games were less about the world’s best athletes competing for medals and more about (actual) amateur athletes competing against each other.

When the United States hosted the Olympics for the first time in 1904, the games had yet to reach the high level of competition and popularity we know today. Although athletes from countries around the world were invited to participate, the games were less about the world’s best athletes competing for medals and more about (actual) amateur athletes competing against each other.

The ultimate decision to host the 1904 Olympic Games in St. Louis, Missouri, created a huge obstacle for international athletes in that travel to the innermost parts of the States was difficult and costly. The only way to travel between continents was by a long and expensive ocean voyage, after which the athletes needed to take about a 1,000-mile train trip. As a result, many countries decided not to participate. Out of the 630 athletes from 12 nations that competed that year, 523 were American, which explains why the United States won so many medals that year (239, with the closest runner up being Germany who won 13).

Perhaps one of the most surprising athletes to compete for his country was Félix de la Caridad Carvajal y Soto, known as Andarín Carvajal or Felix Carvajal, from Cuba. With no formal training and a running technique that left much to be desired, this mailman raised his own money to travel to St. Louis to represent his country in the Olympic marathon race. Despite his work as a mailman, Felix lived his life in poverty and was denied financial assistance from his local government to cover expenses he would incur on his journey to the Olympics. He spent days running around town square and begging people for money to help him on his pursuit. His efforts paid off, and he raised enough money for a trip to New Orleans, then promptly lost his remaining funds on a game of dice… Not to be deterred, he hitchhiked the remaining 650 or so miles to his destination. Due to his jovial nature, he befriended the men on the American weightlifters team who gave him room and board as he prepared for the marathon.

The 1904 marathon for the Olympics started around 3:00 pm in the afternoon in August, with temperatures above 90 degrees. Anyone who knows about summer weather in St. Louis knows that the oppressive heat and humidity are not friends to anyone, certainly not to the 32 men representing four different countries running a 24.85 mile marathon. To make the situation worse, the only access runners had to water on the course was at miles six and twelve. For some, especially those who didn’t have a support vehicle or support staff to aid them, that made for a very long and torturous race.

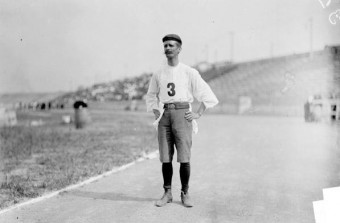

Carvajal showed up to the starting line wearing a long-sleeved shirt, pants, and boots. Considering other runners were in shorts and tank tops, we can only assume these were the only clothes he had with him. (Legendary athlete Jim Thorpe once did something similar at the Olympics, wearing different sized shoes, neither of which fit him, that he’d scrounged out of a garbage bin shortly before a race.) As for Carvajal, seconds before the start of the race, an American discus thrower found a pair of scissors and made a mock pair of shorts out of Carvajal’s pants for more athletic attire.

Carvajal showed up to the starting line wearing a long-sleeved shirt, pants, and boots. Considering other runners were in shorts and tank tops, we can only assume these were the only clothes he had with him. (Legendary athlete Jim Thorpe once did something similar at the Olympics, wearing different sized shoes, neither of which fit him, that he’d scrounged out of a garbage bin shortly before a race.) As for Carvajal, seconds before the start of the race, an American discus thrower found a pair of scissors and made a mock pair of shorts out of Carvajal’s pants for more athletic attire.

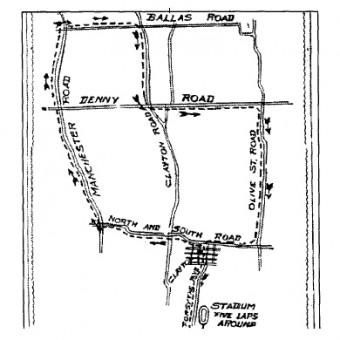

The start of the race required runners to complete five laps around the stadium before heading off into St. Louis County. The course was not shy on delivering obstacles for the athletes. Through the streets of St. Louis, in order to stay on the course, runners had to dodge cars, delivery wagons, railroad trains, trolley cars, and people walking their dogs. In places, the roads were covered with cracked stone that the runners had to pick their way through. If all that wasn’t enough, there was the seven 100-300 foot hills, noxious exhaust fumes from the early automobiles (including support vehicles and others following the runners along as they went), and the extreme amounts of dust kicked into the air by these vehicles and horses.

Car fumes and dust, coupled with the heat and humidity, soon took its toll on the runners. One of the first ones to drop out of the race was John Lordon of Massachusetts. In 1903 Lordon won the Boston Marathon, but he only made it ten miles in this Olympic marathon before he started vomiting and pulled out of the race.

Car fumes and dust, coupled with the heat and humidity, soon took its toll on the runners. One of the first ones to drop out of the race was John Lordon of Massachusetts. In 1903 Lordon won the Boston Marathon, but he only made it ten miles in this Olympic marathon before he started vomiting and pulled out of the race.

The winner of the 1904 Boston Marathon, Michael Spring of New York, started out the Olympic marathon strong, leading the pack, but when ascending of one of the steep hills, he collapsed from exhaustion and couldn’t continue. William Garcia from San Francisco almost became the first death in the Olympic Games when he was found lying unconscious in a ditch on the course and was raced to the hospital. Fortunately, despite the extreme amount of dust he had inhaled doing a major number on his esophagus and lungs, he eventually recovered and was able to race again.

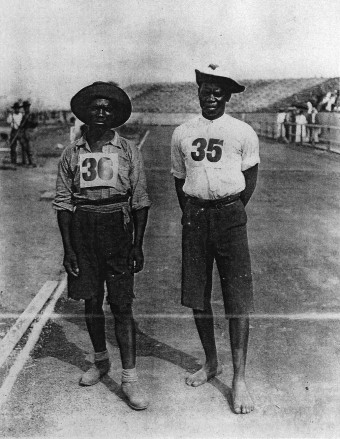

Another notable feature of this particular marathon was that it saw the first two black Africans competing in the Olympics. However, neither Len Taunyane nor Jan Mashiani were seasoned marathon runners, but both had served as dispatch runners in the South African Boer War. They were in town as part of the Boer War exhibit at the World’s Fair and decided to enter the race on a whim. Both finished, placing ninth and twelfth respectively. It was reported that Tau probably would’ve placed higher if he hadn’t been chased over a mile off the course by a wild dog.

Another notable feature of this particular marathon was that it saw the first two black Africans competing in the Olympics. However, neither Len Taunyane nor Jan Mashiani were seasoned marathon runners, but both had served as dispatch runners in the South African Boer War. They were in town as part of the Boer War exhibit at the World’s Fair and decided to enter the race on a whim. Both finished, placing ninth and twelfth respectively. It was reported that Tau probably would’ve placed higher if he hadn’t been chased over a mile off the course by a wild dog.

American Frederick Lorz was a contender for one of the top spots early on in the race, but he suffered from severe cramps and at nine miles was unable to continue. He decided to hitch a ride in one of the cars back to the stadium, but the car broke down before arriving at its destination. Feeling refreshed, Lorz started running again. When he entered the stadium three hours after the start of the race, the crowd erupted in applause for the “winner.” Unable to resist the crowd, Lorz went along with the facade, racing toward the finish line and basking in the limelight. Perhaps he really was trying to take the credit for the win, or perhaps he was in it for the fun and games like he later claimed. Either way, when it was quickly noted by certain spectators that Lorz had been seen riding in a car during the race, the officials saw no humor in his prank and banned Lorz for life from participating in amateur races. However, less than a year later, the ban was lifted after Lorz apologized for his stunt; he went on to take first in the 1905 Boston marathon.

When another leading runner, Thomas Hicks from the United States learned of Lorz’s supposed win, he begged his two assistants to let him drop out because he was in so much pain. They refused to let him quit. Like many other runners, Hicks’s health took a plunge early in the race and continuously declined as he ran. For some bizarre reason, his handlers refused to give him water to drink during the race, and instead sponged out his mouth using warm distilled water and then proceeded to feed him egg whites and strychnine. (Yes, strychnine.)

At the time, strychnine was used in small doses as a performance enhancing drug. Anything but small doses would, of course, kill the athlete via asphyxiation due to paralysis of the respiratory muscles. However, in small doses, strychnine was believed to provide a performance boost via the muscle spasms it relatively quickly induces.

Unfortunately for Hicks, besides refusing him water to drink, his handlers didn’t stop with one dose of the poison. In total, during the race he was given approximately 2-3 mg of strychnine, plus accompanied raw eggs and brandy each dose.

Unsurprisingly, with the extreme heat, humidity, dust clouds, dehydration, and being fed rat poison, Hicks’ condition continually grew worse and he ultimately became delusional. Nevertheless, he continued to put one foot in front of the other and soldiered on.

Entering the stadium for the last stretch of the race, Hicks required physical assistance from his handlers who had to practically carry him over the finish line. Of course, this would result in a disqualification in today’s Olympics, but in 1904 the act was completely legal. Hicks was unable to initially receive his gold medal given that he fell unconscious at the finish line and it took doctors about an hour to revive him. Close to death, fortunately, he eventually recovered, though retired from competing in marathons. With a time of 3:28:53, Hicks’s feat is the slowest time for a men’s Olympic marathon in history.

Entering the stadium for the last stretch of the race, Hicks required physical assistance from his handlers who had to practically carry him over the finish line. Of course, this would result in a disqualification in today’s Olympics, but in 1904 the act was completely legal. Hicks was unable to initially receive his gold medal given that he fell unconscious at the finish line and it took doctors about an hour to revive him. Close to death, fortunately, he eventually recovered, though retired from competing in marathons. With a time of 3:28:53, Hicks’s feat is the slowest time for a men’s Olympic marathon in history.

The United States claimed the silver and bronze medals in the marathon as well when Albert Corey crossed the finish line six minutes after Hicks, soon followed by Arthur Newton with a time of 3:47:33. Although both runners struggled with the heat and dust and slowed to a walk during certain parts of the race, neither seemed to have it worse than Hicks.

Meanwhile, Felix Carvajal ran at a comfortable pace. Unable to resist charming the spectators who lined up along the way, Felix often stopped to chat with them in his broken English and crack jokes. With his upbeat and good spirited attitude, he won the hearts of many along the course. When he begged for peaches from the occupants of an accompanying car and was refused, he teasingly snatched a couple from them anyway and kept on running, eating the peaches as he ran.

Most accounts of the marathon say Carvajal needed a bit more sustenance, so he snuck into an apple orchard and plucked two of the juicy fruits from the boughs. Supposedly the apples didn’t sit well with him and he suffered from cramps, which forced him to rest and purportedly take a cat-nap before continuing the race. However, it should be noted that there is no contemporary evidence that the apple/nap part of this story ever took place, with the first account of it popping up in William Henry’s 1948, An Approved History of the Olympics. Regardless, the contemporary accounts of Carvajal’s approach to the race seem to describe an individual having a blast, while many other racers struggled to overcome bodily limitations.

Felix Carvajal crossed the line in fourth place, though what his time was is unknown today. Compared to the other racers, he was described as seeming to float across the finish line. Aside from probably being a bit tired and hungry, the heat and humidity didn’t seem to have too much of an effect on the Cuban. While it’s not known how far behind third place he was, accounts of the day indicate if it wasn’t for his numerous stops to chat with people during the race, Carvajal may well have won. Whatever the case, the 1904 Olympics ended up being the only international competitive race Carvajal would compete in.

In the end, only 14 of the original 32 racers managed to finish the race.

As for the victor, although the “assistance” Hicks received mostly proved to be detrimental, he was able to finish the race thanks to being carried along near the end- a fact that resulted in some feeling like he should have been disqualified. After the race, a complaint towards this end was filed by Everett Brown, the chairman for the Chicago Athletic Association. However, the Olympic Games director refused to consider the matter and Hicks remained the winner.

As for the victor, although the “assistance” Hicks received mostly proved to be detrimental, he was able to finish the race thanks to being carried along near the end- a fact that resulted in some feeling like he should have been disqualified. After the race, a complaint towards this end was filed by Everett Brown, the chairman for the Chicago Athletic Association. However, the Olympic Games director refused to consider the matter and Hicks remained the winner.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- When Art was an Olympic Sport

- How Much are Olympic Gold Medals Worth?

- That Time a 61 Year Old Potato Farmer Won One of the World’s Most Grueling Athletic Competitions

- That Time an Olympic Rower Stopped to Let Some Ducks Swim By and Still Won the Gold Medal

- The Heroic Death of Chariots of Fire’s Eric Liddell

Bonus Facts:

- In the 1500s most Roman Catholic countries & Scotland adopted the Gregorian Calendar (established by Pope Gregory XIII to compensate for the errors in time that had built up over centuries) over the Julian Calendar (introduced by Julius Caesar in 45 BC). A lot of protestant countries, however, ignored this new calendar for another 200 or so years. England stuck to the Julian Calendar until 1751 before finally making the switch. Orthodox countries took even longer to accept the change. Russia, for one, did not convert to the Gregorian calendar until after the Russian Revolution in 1917. What does this have to do with the Olympics? In 1908, the Russian Olympic team arrived 12 days late to the London Olympics because of this.

- Given all the challenges the runners faced, many deemed the marathon as too dangerous and the director of the 1904 Olympic games indicated that the event may not return for the 1908 games. Not only did the marathon return, but officials extended the distance to 26 miles and it has remained an event at the Olympics ever since. However, like many other things in life, women had to fight for their right to an Olympic marathon event. Deemed too dangerous because of the toll it would take on a woman’s health, the longest distance women were allowed to run in the Olympics was 800 meters. Through a lot of determination, women were finally able to participate in their own Olympic marathon when it became an official event in 1984. If you’re interested in a fascinating story concerning women and marathons, see: The First Woman to Officially Run in the Boston Marathon.

- The first drug disqualification in the Olympics occurred in 1968 when Hans-Gunnar Liljenwall from the Swedish pentathlon team. The drug he was disqualified for? Alcohol.

- The Olympic Marathon, By David E. Martin, Roger W. H. Gynn

- America’s First Olympics: The St. Louis Games Of 1904 by George R. Matthews

- Everything You Know About Marathons Is Wrong

- Andarín Carvajal

- ROUGH DAY AT THE 1904 OLYMPIC MARATHON

- Olympic Moments: Felix Carvajal’s Long Road to St. Louis (1904)

- The 1904 Olympic Marathon May Have Been the Strangest Ever

- The Marathon From Hell

- FELIX CARVAJAL AND THE SAINT LOUIS OLYMPICS

- St. Louis Olympic Games

- Wacky Tales from Olympics Past

- Facts About Strychnine

- 8 Unusual Facts About the 1904 St. Louis Olympics

- 1904 Olympic Medal Total

- Thomas Hicks

- Strychnine

- Frederick Lorz

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

I was surprised to see the article mentioning the athletes “running a 24.85 mile marathon,” because I knew that marathons today have a length of about 26.22 miles. I interrupted my reading to do a little research, which led me to learn the following …

1. When the modern Olympics began in Athens in 1896, a race of forty kilometers, or 24.85 miles, was held to commemorate the legend of Pheidippides, a messenger who was said to have made a (fatal for him) run from Marathon to Athens to announce a Greek victory over the Persians at the Battle of Marathon in 490 B.C..

2. For some reason, officials at the 1900 Olympics in Paris extended the marathon to just over twenty-five, but the former distance, 24.85 miles, was restored in St. Louis in 1904.

3. That did not last long, because officials at the 1908 Olympics in London re-extended the marathon, this time to the distance that persist today — 26 miles and 385 yards.

I am going to change the subject now and quote from the article:

“In the 1500s most Roman Catholic countries & Scotland adopted the Gregorian Calendar … A lot of protestant countries, however, [etc.].”

The first correction I would ask you to make is to strike the word, “Roman.” For numerous reasons (too lengthy to spell out here), a writer should never use the term, “Roman Catholic,” to speak of a Church that always refers to herself simply as “Catholic.” [If you check the (Eastern and Western) Codes of Canon Law (of the 1980s), the documents of the Second Vatican Council (of the 1960s), and the new “Catechism of the Catholic Church” (of the 1990s), and you will find ZERO references to “Roman Catholic(ism). If you were ever to come across an official Catholic reference to the “Roman Church,” that would be a reference to the Diocese of Rome only, not to the universal Church.]

The second correction that you should make is the deletion of references to “Catholic countries” and “protestant countries,” because such things do not exist. In no century, including the 16th, has any country in the world ever been completely Catholic or protestant. A writer should instead speak of the “predominance” of the presence of one religious group or another, if a true majority really exist in a nation.

The third correction that you should make is to drop the reference to “Scotland.” By referring to “Catholic countries & Scotland,” the author showed his mistaken belief that Scotland was predominantly protestant at the time of the publication of the Gregorian Calendar. In fact, it was predominantly Catholic, which is why the reference to Scotland should be dropped.

The fourth correction that you should make is to delete the word, “most,” thus dropping the author’s erroneous implication that some predominantly Catholic nations did not adopt the new calendar “in the 1500s.” All predominantly Catholic nations adopted it before 1600.

Here, therefore, is how the troublesome sentences should have been worded:

“In the 1500s, all of the predominantly Catholic countries adopted the Gregorian Calendar … Many of the predominantly protestant countries, however, [etc.].”

Thank you for an otherwise fascinating article.