There and Back Again- The Story of Able and Miss Baker… In Space

Over two decades before Buzz and Neil put their feet on the Moon, humans were already preparing for that day by sending other living organisms to space. In 1947, the United States blasted fruit flies into space in a captured Nazi V-2 rocket. Alongside packets of rye and cotton seeds, the original intention of the flies’ mission was to determine the effects of cosmic rays on living organisms. When the flies’ canister parachuted back to Earth, scientists were relieved to find the fruit flies still alive. In 1948, America took the next step and sent a monkey to space. This didn’t go as well. Albert I, a rhesus monkey, was anesthetized before even being put on the V-2 Blossom. While the rocket launched successfully, scientists later speculated that Albert probably wasn’t alive for the flight due to having likely suffocated in the very cramped capsule before takeoff. Even if he was alive for the trip, with the rocket only reaching 39 miles (62 km) in altitude, the parachute mechanism failed and the rocket had a violent crash landing, which would have likely killed him. At least the name “Albert” lived on because, from that point on, the proceeding tests involving monkeys in the United States were known as the “Albert project.”

Over two decades before Buzz and Neil put their feet on the Moon, humans were already preparing for that day by sending other living organisms to space. In 1947, the United States blasted fruit flies into space in a captured Nazi V-2 rocket. Alongside packets of rye and cotton seeds, the original intention of the flies’ mission was to determine the effects of cosmic rays on living organisms. When the flies’ canister parachuted back to Earth, scientists were relieved to find the fruit flies still alive. In 1948, America took the next step and sent a monkey to space. This didn’t go as well. Albert I, a rhesus monkey, was anesthetized before even being put on the V-2 Blossom. While the rocket launched successfully, scientists later speculated that Albert probably wasn’t alive for the flight due to having likely suffocated in the very cramped capsule before takeoff. Even if he was alive for the trip, with the rocket only reaching 39 miles (62 km) in altitude, the parachute mechanism failed and the rocket had a violent crash landing, which would have likely killed him. At least the name “Albert” lived on because, from that point on, the proceeding tests involving monkeys in the United States were known as the “Albert project.”

Albert II’s fate was no better, though he was given more breathing room and survived the flight. But after reaching a maximum altitude of 83 miles, officially crossing the Kármán line becoming the first primate in space, he died upon impact when the parachutes failed.

Alberts III through V all were sent into space and none survived, either due to impact, mid-air explosion or a complication during the flight. Until 1959, no primate had ever returned to Earth from space alive.

Meanwhile in the Soviet Union, the Russians were sending a different type of animal into the great unknown. Around the same time the Americans were performing their monkey experiments, the Russians were sending rabbits, mice and rats. Then, they decided dogs were the next logical step due to, as Vladimir Yazdovsky, the head of the biological program for space research at the Institute for Aviation Medicine in Moscow, said: “We selected dogs as biological objects because their psychology is very well-studied, they adapt well to training, are very communicative, and social with people.” It also helped that dogs were readily available, with Moscow awash with stray canines at the time.

In August of 1951, Dezik and Tsygan (meaning “Gypsy”) was launched into the sky. After going to an altitude of 62 miles (100 km), the capsule with the two canines crashed rather hard on Earth, leaving Russian scientists fearing the worst. When they opened the capsule, however, barking greeted them. Dezik and Tsygen were the first beings (besides fruit flies and perhaps microbes) to go into space and return to Earth safely – save for a little motion sickness.

Over the next eight years, the Soviets sent many dogs to space, of which a good portion came back to Earth alive and relatively well. Famously, in 1957, a pup named Laika became the first to circle the Earth. Whether Laika was actually still alive during that first orbit is a source of much debate, with her early death likely due to overheating and panic, though it should be noted that, sadly, there were no plans to recover Laika after the orbit. One of the scientists involved in Laika’s mission, Oleg Gazenko, later stated of this, “Work with animals is a source of suffering to all of us… The more time passes, the more I’m sorry about it. We shouldn’t have done it… We did not learn enough from this mission to justify the death of the dog.”

While the Russians certainly did have success with canines, dogs are a far cry from humans. Primates, on the other hand, are in the same family.

Determined to finally get their own efforts right, NASA choose two monkeys for its next mission in 1959. The first was another female rhesus monkey named Able. Picked from a lot of 24 that came from a zoo in Independence, Kansas, Able was chosen for the mission with direct orders from President Eisenhower. This was due to the original primate space cadet being Indian-born and, since some in India consider the rhesus monkey sacred, President Eisenhower thought it would be best for political reasons to send an American-born rhesus monkey to space instead.

The second monkey chosen for the mission was also selected from a large group, this time of 25, purchased from a pet shop in Miami. The two year old, one pound South American-born Miss Baker was determined to be the best of the bunch, due to her propensity to not seem to mind being confined for long periods, her docile nature, intelligence, seeming to enjoy being handled, and general friendliness towards humans, with her nickname becoming “TLC” (Tender Loving Care). With the selections made, the two monkeys were sent into training for their date with history.

Each monkey was fitted with specially made suits with sensors to track pulse, body temperature and movement. Able’s was tightly fitted, allowing for minimal movement, but giving her enough room to perform a simple task on the flight- she was trained to press a button whenever a red light flashed, so that the humans below could test her coordination and focus while in space.

Each monkey was fitted with specially made suits with sensors to track pulse, body temperature and movement. Able’s was tightly fitted, allowing for minimal movement, but giving her enough room to perform a simple task on the flight- she was trained to press a button whenever a red light flashed, so that the humans below could test her coordination and focus while in space.

Miss Baker’s suit was lined with foam rubber and leather and she was fitted into a very small life support capsule, nearly the size of a thermos, which gave her no room to move. Both monkeys had fiberglass helmets.

At 2:35 a.m. on May 28, 1959, the giant Jupiter AM-18 blasted into the sky, reaching speeds in excess of 10,000 mph, with the two primates seated not-so-comfortably in the nose cone. Their flight lasted about 17 minutes before they plunged into the ocean about 250 miles southeast of San Juan, Puerto Rico. The recovery team immediately went in search of them. Initially, there was fear that the capsule had sunk, much like a predecessor of theirs. But then the crew spotted it bobbing in the water.

Shortly thereafter, a message came through to the Cape Canaveral control room, “Able Baker perfect. No injuries or other difficulties.” The two monkeys had become the first primates to travel in space and return home safely.

Able and Miss Baker arrived back to the United States to a hero’s welcome, first going to their own private officer quarters with recently installed air conditioning. Then, they were flown to Washington DC for a “welcome back” press conference. There, correspondents “pushed each other and clambered over chairs to get closer,” to the monkeys reported The New York Times. As for the heroes themselves, “the monkeys were far less excited than the humans. They munched peanuts and crackers.” Able and Miss Baker were awarded medals and merits. A month later, they were on the cover of LIFE Magazine. For Able, unfortunately, fame was short lived.

Able and Miss Baker arrived back to the United States to a hero’s welcome, first going to their own private officer quarters with recently installed air conditioning. Then, they were flown to Washington DC for a “welcome back” press conference. There, correspondents “pushed each other and clambered over chairs to get closer,” to the monkeys reported The New York Times. As for the heroes themselves, “the monkeys were far less excited than the humans. They munched peanuts and crackers.” Able and Miss Baker were awarded medals and merits. A month later, they were on the cover of LIFE Magazine. For Able, unfortunately, fame was short lived.

It was supposed to be a minor operation, one simply to remove leftover electrodes from the trip four days earlier. Doctors were very careful with her, but after administering anesthesia, the monkey inexplicably went into cardiac arrest and stopped breathing. After spending nearly two hours attempting to save Able’s life, the doctors working on her accepted the inevitable- she was gone. Able died on June 1, 1959, only days after returning home. Today, she’s preserved and on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC.

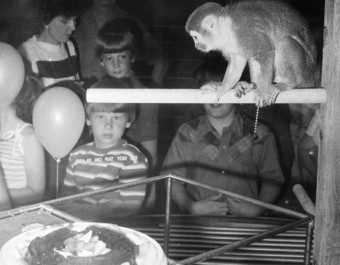

As for Miss Baker, she went on to live a life worthy of an American hero. After her media blitz, she retired to the Naval Air Training Station in Pensacola in a custom built home. Three years later, she was “married” to a Peruvian squirrel monkey called “Big George” in a nice naval ceremony. In 1971, the happy couple moved to U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

As for Miss Baker, she went on to live a life worthy of an American hero. After her media blitz, she retired to the Naval Air Training Station in Pensacola in a custom built home. Three years later, she was “married” to a Peruvian squirrel monkey called “Big George” in a nice naval ceremony. In 1971, the happy couple moved to U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

In 1979, Big George died but, after a brief mourning period, Miss Baker remarried. In a ceremony in Huntsville, she took her second vows with a monkey named Norman. Fitted with a wedding dress, Miss Baker tore it off, apparently not much for formal wear.

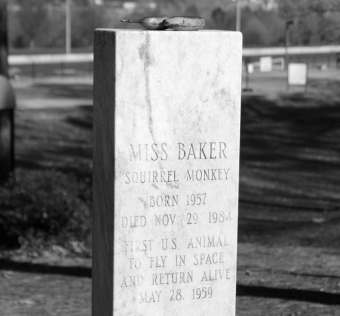

Five years later, on November 29, 1984, Miss Baker died, living to the ripe old age of 27. In addition to being a space explorer, Miss Baker was also the oldest living squirrel monkey on record. For reference, the average lifespan of a squirrel monkey in the wild is just 15 years and in captivity around 20. Three hundred people, and Norman, attended the funeral in Huntsville, Alabama, on the grounds of the United States Space & Rocket Center. She’s buried at the Space Center with an often-visited marker.

While Miss Baker and Able may not get the same recognition as Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong, they are, perhaps, among the most famous monkeys in history, getting the chance to do something most humans only ever dream about.

While Miss Baker and Able may not get the same recognition as Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong, they are, perhaps, among the most famous monkeys in history, getting the chance to do something most humans only ever dream about.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Surprisingly Long Time You Can Survive in Space Without a Space Suit

- A Brief History of the Ballpoint Pen and Whether NASA Really Spent Millions Developing a Pressurized Version Instead of Just Using Pencils

- Can the Great Wall of China Really Be Seen from Space?

- Why Neil Armstrong Got to Be the First to Step on the Moon

- The United States Once Planned On Nuking the Moon

Bonus Fact:

- The Kármán Line, named after Hungarian-American physicist Theodore von Karman, is the boundary that exists 62 miles above sea level and is generally accepted as the line between the Earth’s atmosphere and outer space.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Please correct the error in the sentence quote below. Please resolve to show professionalism, in the future, by making such corrections before articles are posted. Thank you.

“Albert I, a rhesus monkey, was anesthetized before even being putting on the V-2 Blossom.”

Yikes. Snooty much, JF?

Another typo got you clutching your pearls? As Daven has frequently pointed out they, like shit (as the Americans say), happen. I’m sure his level of contrition is adequate, as opposed to your levels of patronization and derision, which are over the top.

Clearly you find this distressing, as do I, but you have no right to sniff haughtily, insult him, and impugn his professionalism.

Criticize if you must his all-too-human inability to get Every Single Thing on his site absolutely perfect. I’m sure it rankles him plenty, and please note that he fixes every glitch as soon as he is made aware of it (see above, re: professionalism).

I, no doubt like you, would like nothing better than for everything I read (and especially write) on the internet to be letter-perfect, grammatically correct and spelled properly. That will never happen. However to anybody familiar with this site, it’s perfectly clear that Daven, in this matter, is one of us, and not one of them. He deserves better than your self-righteous insults.

Ah, but what is little known about the fruit flies exposed to cosmic rays was one’s propensity to burst into flame, another to stretch and contort his body, a third was seemingly encased in biological rock, while the final fly disappeared every now and then.

Good one.