Dustbin of History: The Fascinating Saga of the Comstock Lode

Practically everybody has daydreamed about prospecting for gold and striking it rich. But what happens after the big strike? Here’s the amazing tale of one of the biggest bonanzas in U.S. history.

Practically everybody has daydreamed about prospecting for gold and striking it rich. But what happens after the big strike? Here’s the amazing tale of one of the biggest bonanzas in U.S. history.

KILLING TIME

In January 1848, gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, California, sparking the Gold Rush that brought more than 300,000 people to the territory. In the spring of 1850, some prospectors heading for the California gold fields stopped at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains about 20 miles outside of modern-day Reno, Nevada, to wait for the snow to melt before they continued over the mountains. Why not look for gold while they waited? They fanned out along the Carson River’s edge and up a stream that fed into the river from a nearby canyon. And sure enough, they did manage to find some gold…but not enough to justify staying put. So after the snow melted a few weeks later, they moved on to California. Before they left, though, they named the spot “Gold Canyon.”

PAY DIRT

Word of the discovery at Gold Canyon spread, and each spring as a new wave of settlers and prospectors headed to California along the same route, many stopped there long enough to pan for gold. As the years passed and the original deposits were played out, prospectors started exploring farther afield. In January 1859, a prospector named James “Old Virginny” Finney and three friends took advantage of some good weather and went prospecting on top of a low hill in Gold Canyon where the dirt was yellower than in the surrounding lowlands. Old Virginny thought that was a good sign. When they started testing the soil, each pan yielded about 15¢ worth of gold. Not exactly Sutter’s Mill, but it was enough to justify staking a claim and exploring the area further.

In those days, tradition and mining law dictated that no miner could stake a claim larger than he could work himself. Old Virginny and his associates each filed a claim for a 50-by-400-foot area, and over the next few days some other miners filed adjacent claims. Many more made trips to the site to look around, but for most of them, 15¢ a pan wasn’t enough gold to make them abandon the claims they were already working.

DOWNS AND UPS

When Old Virginny and the others finished washing all the surface dirt through their “rockers”—mining equipment resembling baby cradles that rocked back and forth to separate out the gold—they dug deeper. As they did, the amount of gold steadily increased, first to $5 per day for each miner, then $12, and for a time as high as $20, at a time when gold sold for $13.50 an ounce.

So why isn’t the Comstock Lode known as the Finney Lode or the Old Virginny Lode? Because as the months passed and the miners dug deeper, they eventually hit a deposit of difficult-to-work clay that had very little gold in it. Most deposits of gold are small, so when the miners ran out of the easy diggings they assumed they’d found all there was. That’s what happened to Old Virginny: the gold ran out, so he moved on.

That June, just a mile down the hill, two miners named Peter O’Riley and Pat McLaughlin struggled to make a profit on a 900-foot-long claim they’d staked for themselves. The claim was yielding only one or two dollars’ worth of gold a day, and the men had heard about richer claims near the West Walker River, about 25 miles away. But they decided to stick around a little longer, probably until they made enough money to pay for the move.

It takes water to sift gold out of sand and dirt, and the closest water source was a tiny spring that the men decided to dam up with some strange bluish sand they’d uncovered nearby. Almost on a whim, they tossed some of the odd sand into the rocker to see if it contained any gold. It was heavy and difficult to work with, but when they cleared it away they were stunned to see that the entire bottom of the rocker was covered in a layer of shimmering gold. Where Old Virginny had recovered gold by the ounce, O’Riley and McLaughlin were mining it by the pound.

RANCHO COMSTOCKO

So why isn’t the Comstock Lode known as the O’Riley Lode or the McLaughlin Lode? Because later that same day, another miner, Henry “Old Pancake” Comstock, happened to ride by while the men were celebrating their good fortune. When Comstock saw the gold, he hopped off his pony and told the two men that they were prospecting on land that he and a partner had already claimed for a ranch. In those days, you could claim unoccupied land for a ranch just as easily as you could stake a mining claim. Comstock told the “trespassers” that if they would let him and his partner, Emmanuel Penrod, become equal partners in the claim, he wouldn’t take them to court. Furthermore, if he and Penrod were given 100 feet of the claim to work by themselves, he’d even let them use the water from “his” stream.

DEAL OR NO DEAL

Nearly 150 years have passed since then, and in all that time no record of a ranch claim by Comstock has ever been found. But O’Riley and McLaughlin didn’t know that, and in those days it was common to settle mining disputes quickly without resorting to lawsuits—why waste money on lawyers when nobody knew how long the gold would last? Even the best claims might peter out after a month or two.

O’Riley and McLaughlin took the deal…and Comstock started getting credit for their discovery. Comstock “was the man who did all the heavy talking,” Dan DeQuille wrote in his 1876 book A History of The Big Bonanza. “He made himself so conspicuous on every occasion that he soon came to be considered not only the discoverer but almost the father of the lode. People began to speak of the vein as Comstock’s mine, Comstock’s lode…while the names of O’Riley and McLaughlin, the real discoverers, are seldom heard.”

THE BAD WITH THE GOOD

Beneath the crumbly blue dirt was a firmer, compacted blue stone that yielded even more gold. On good days, the men pulled more than $1,000 worth of gold from the earth, more than 5½ pounds of gold a day. When the men hit a really rich patch, they might collect $150 worth in a single pan of dirt. The only frustration was the fact that the strange blue dirt clogged the rockers and other mining equipment terribly. “For weeks they let it go to waste,” DeQuille wrote, “throwing it anywhere to get it out of the way. They not only did not try to save it, but constantly cursed it. It was the great drawback.”

GET A LODE OF THIS

When you’re pulling gold out of the earth by the pound, word of what you’re doing has a way of getting out. In June 1850, a rancher named B. A. Harrison, living in Truckee Meadows, about 10 miles away from the Comstock mine, learned of the strike and went to see it for himself. He collected some samples and brought them to the town of Grass Valley, where he gave pieces to friends. One of them, a local judge (and a miner) named James Walsh, had the ore “assayed,” or analyzed, to see what was in it and how much it was worth.

The assayer estimated that an average ton of the ore would yield about $969 worth of gold. No surprise there; Harrison and Walsh knew there was plenty of gold in the ore. But what really stunned everybody—including the assayer, who was so incredulous that he tested the ore a second time—was that each ton would also yield nearly $3,000 worth of silver.

Silver? What silver? The assayer explained to Harrison and Walsh that the blue dirt that had proved so frustrating to the prospectors was actually silver sulfide, or silver ore, and a very rich deposit of it at that. It was, according to the experts, “an almost solid mass of silver.” As Harrison had seen with his own eyes, the exasperated prospectors had already dug up tons and tons of the blue ore and were dumping it in huge waste piles all over the place. They had absolutely no idea what they had stumbled onto.

SHHH!

That night, Harrison, Walsh, and a few other associates made plans to sneak out of town the following morning without attracting attention, so that they could stake their own claims next to the existing ones and maybe even buy out the original claims if they could. But who could keep that big a secret? If you won the lottery on Monday evening, could you really keep it to yourself until Tuesday morning? At least one person must have talked, because by the time the men were ready to leave the following morning, Grass Valley was buzzing with news of the discovery.

SEEING IS BELIEVING

It took just days for word of the strike to spread from Grass Valley to the California gold country. Soon miners who’d been unlucky there began abandoning their existing claims and heading east. But the real rush didn’t begin until after Judge Walsh had shipped nearly 40 tons of the ore to San Francisco in fall of 1859, where it yielded more than $118,000 worth of gold and silver.

Many of San Francisco’s leading citizens were men who had struck it rich during the gold rush of 1849 and had managed to hang onto their money since then. They weren’t the kind of fellows who took to the hills chasing every rumor of a new strike. But seeing the newly minted bullion in the offices of Walsh’s bankers made believers out of everyone, and soon they, too, were on their way over the Sierra Nevadas. By the first week of November, when snowfall blocked the mountain passes for the rest of the winter, several hundred people—from the wealthiest speculators to the lowliest prospectors—had made their way to the area and were riding out the winter in tents or whatever shelter they could improvise.

DOWN…AND OUT

Mining the surface gold and silver out of a deposit like the Comstock Lode is easy enough: the ore was so soft, in fact, that it could be mined with just a shovel. But once all the surface ore is gone and prospectors have to start digging deeper into the earth to get at the rest, mining becomes a much more dangerous and expensive proposition. And who knew how long the rich deposit would hold out? Each time the prospectors lifted a spadeful of ore, they faced the very real prospect of finding nothing but worthless dirt or rock underneath.

The thinking among experienced prospectors was that the best way to profit from a lucky strike was to sell out before the limits of the strike had been discovered—hopefully at top dollar to feverish investors foolish enough to think the good times would last forever. So when the big money boys from San Francisco rolled into camp, many of the original claim holders sold out for what must have seemed like obscene profits at the time and happily went on their way.

FINDERS, WEEPERS

Pat McLaughlin sold his claim for $3,500. His partner, Peter O’Reilly, held out the longest of all the original stakeholders, eventually selling out for $40,000, after collecting about $5,000 in dividends.

Henry Comstock sold his claim to Judge Walsh for $11,000 and used the money to open mercantile stores in Carson City and Silver City, both of which he hoped would profit from the mining trade he’d helped create. No such luck—both stores failed. Comstock spent the rest of his life roaming the American West, looking for a second mother lode. No luck there, either. In September 1870, Comstock—by now broke, broken, and mentally deranged—committed suicide in Bozeman, Montana.

NAMING RIGHTS

Old Virginny, the man who made the first discovery, was also one of the very first to sell out, reportedly surrendering his interest in the mine for “an old horse, worth about $40, and a few dollars in cash.” Another version of the story says he got a couple of blankets and a bottle of whiskey in the bargain as well. It didn’t make much difference either way—Old Virginny wouldn’t have lived long enough to enjoy his riches even if he’d gotten any. In the summer of 1861, he was thrown from a bucking mustang while drunk and died from head injuries a few hours later.

SELLERS’ REMORSE

It didn’t take long for the discoverers of the Comstock Lode to realize how wrong they’d been to sell out so early. Having thousands of dollars in their pockets, perhaps for the first time in their lives, must have felt wonderful in an age in which the highest paid miners made $4 a day. In the 1850s, $1,000 had more purchasing power than $100,000 does today.

But as the new owners of the Comstock claims dug deeper into the earth, not only did the ore deposit not peter out as the discoverers had expected it would—it grew larger than the most experienced mining engineers had ever seen before. Who knows how many sleepless night were spent by the early sellouts, anguishing over what might have been had they held onto their claims for just a little longer.

WIDE LODE

Normally, such rich deposits of gold and silver are found in narrow cracks in the Earth known as veins or lodes. They’re deposited there by geothermally heated water, which dissolves trace amounts of gold, silver, or other minerals at deeper levels in the Earth’s crust. Then, as the water rises through cracks in the crust and gets near the earth’s surface, the hot water cools and the minerals come out of suspension and are deposited in high concentrations in the cracks.

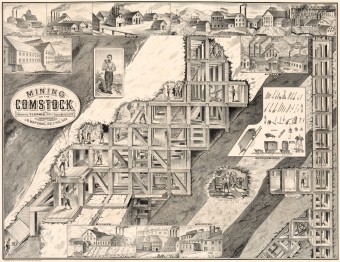

Such cracks are usually quite narrow—no more than a few feet wide. But not this time: by the time the miners had dug 50 feet down, the vein had grown to 10 to 12 feet wide, and as the miners dug deeper, it grew wider still. When they reached a depth of 180 feet in December 1860, the vein was more than 45 feet across—so wide, in fact, that traditional methods of reinforcing the mine against cave-ins weren’t good enough to do the job. A better technique of timbering had to be found, and in late 1860 a mining engineer named Philipp Deidesheimer found one. Instead of just putting posts against each wall and running a horizontal beam across the top to reinforce the ceiling, Deidesheimer used six-foot lengths of heavy timber to build giant cubes that could be stacked like building blocks to any height, width, or depth.

THE MONEY PIT

Once this and a few other engineering challenges were solved, the Comstock Lode began to produce valuable ore faster than the mining companies could process it. Traditional horse-powered ore processing machines called arrastras soon gave way to giant steam-powered mills that by the end of 1861 could process more than 1,200 tons of ore per day. More than $2.5 million worth of gold and silver bullion was pulled out of the mines that year; the number more than doubled to $6 million in 1862 and doubled again to more than $12.4 million in 1863.

Once this and a few other engineering challenges were solved, the Comstock Lode began to produce valuable ore faster than the mining companies could process it. Traditional horse-powered ore processing machines called arrastras soon gave way to giant steam-powered mills that by the end of 1861 could process more than 1,200 tons of ore per day. More than $2.5 million worth of gold and silver bullion was pulled out of the mines that year; the number more than doubled to $6 million in 1862 and doubled again to more than $12.4 million in 1863.

The miners and the mine owners were making plenty of money, but in these early years nobody made out better than the lawyers. When it became evident that the Comstock Lode was one gigantic ore deposit instead of many small ones, the owners of the original mining claims wanted it all. They filed suit against newer operators to drive them out of business. By the time they succeeded in 1865, more than $10 million—the equivalent of $14 billion today and nearly 20% of the entire production of the mines up to that point—had been spent on lawsuits.

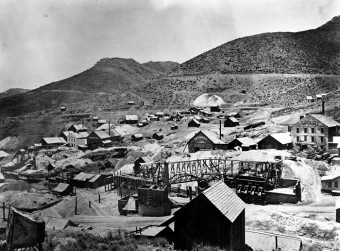

BOOM TOWN

As the mine roared to life, so did the city being built on top of it. In the winter of 1859, miners who’d lacked the foresight to bring their own tents with them to Virginia City had had to tunnel into the hillsides for shelter or squat in hovels made of stone, mud, and sagebrush. By the following spring, however, more than a dozen prominent stone buildings had already been built, as had dozens more of wood. Hundreds more went up before the year was out.

As the mine roared to life, so did the city being built on top of it. In the winter of 1859, miners who’d lacked the foresight to bring their own tents with them to Virginia City had had to tunnel into the hillsides for shelter or squat in hovels made of stone, mud, and sagebrush. By the following spring, however, more than a dozen prominent stone buildings had already been built, as had dozens more of wood. Hundreds more went up before the year was out.

The presence of so many miners with money to burn and no place to burn it attracted scores of merchants and aspiring businessmen who hoped to profit by providing them with goods and services. Soon the wagon trains hauling goods and supplies into the city stretched for miles on end. By the end of 1860, the settlement that had looked like a refugee camp just a year earlier boasted hotels, boarding houses, restaurants, butcher shops, bakeries, tailor shops, candy and cigar stores, and doctors’ offices. On the seamier side, there were saloons, gambling halls, opium dens, several brothels, and at least one brewery.

That was just in the first year of growth; in the years to come, Virginia City would add paved streets, gas streetlights, schoolhouses, an opera house, an orphanage, five newspapers (26-year-old Samuel Clemens began using the pen name “Mark Twain” while editor of the Virginia City Enterprise), half a dozen churches, telegraph and railroad links to the outside world, and the only elevator between Chicago and California. When a lack of drinking water became a barrier to further growth in the early 1870s, the city ran a seven-mile-long iron pipe up into the Sierra Nevada mountains and began siphoning two million gallons of fresh water into the city every day.

ON THE MAP

By the mid-1870s, Virginia City boasted nearly 30,000 residents and in many respects was the most important community between Denver and San Francisco. The wealth of the Comstock Lode remade the map of the American West and provided the impetus in 1861 to create the Nevada Territory, which became the state of Nevada just three years later. It also helped to spur interest in building America’s first transcontinental railroad, which broke ground in 1863. The city of Reno, Nevada, 17 miles outside of Virginia City, was just a stop on the railroad when it was founded in 1868.

Most of the goods and supplies that went to Virginia City passed through San Francisco, giving that city a major economic boost. San Francisco’s first stock exchange, founded in 1862, was set up to trade Comstock Lode shares. More prominent brick buildings were built in the city in 1861 alone than had been built in all previous years combined, and the pace of development remained high for many years to come.

HAND OVER FIST

In all, more than $320 million worth of gold and silver ore was pulled from the Comstock Lode between 1859 and 1878, the equivalent of between $400 and 480 billion today. And yet for all the wealth that came out of the mines, the overwhelming majority of investors who bought stock in the mining companies over the years lost money in the bargain.

Part of this was due to the fact that the operating costs of the mines were staggering. The mines consumed an enormous amount of resources, including millions of pounds of mercury and other chemicals (used to extract the gold from the ore), more than 600 million board feet of timber, and another 2 million cords of firewood. Wages in Virginia City were some of the highest in the world—compensation for the remote location, the dangers of most mining jobs, and the high cost of living in a community where nearly all of the goods and supplies were brought in from hundreds or thousands of miles away.

IN THE HOLE

As the mine shafts got deeper—the deepest reached nearly ¾ of a mile down—the cost of operating the mines soared higher. At these depths, the mines were constantly at risk of flooding with scalding geothermally heated water. Giant, locomotive-sized water pumps had to be lowered into the shafts to get the water up and out of the mines; the largest of these pumps removed more than a million gallons of water per day. And yet even when the water was removed and cooler fresh air was pumped in from the surface, the temperatures at those depths remained so high that the miners could only work for a few minutes at a stretch before retreating into “cooling-off rooms” to douse themselves with ice water.

As the mine shafts got deeper—the deepest reached nearly ¾ of a mile down—the cost of operating the mines soared higher. At these depths, the mines were constantly at risk of flooding with scalding geothermally heated water. Giant, locomotive-sized water pumps had to be lowered into the shafts to get the water up and out of the mines; the largest of these pumps removed more than a million gallons of water per day. And yet even when the water was removed and cooler fresh air was pumped in from the surface, the temperatures at those depths remained so high that the miners could only work for a few minutes at a stretch before retreating into “cooling-off rooms” to douse themselves with ice water.

THE BUBBLE BARONS

But the biggest reason for the investors’ losing their shirts was the fact that the owners of the mines were more interested in manipulating stock prices than they were in running their companies responsibly. Time and again, when a fresh deposit of rich ore was discovered, the owners had it mined and processed into bullion as rapidly as possible, even at the expense of damaging the deposit and losing gold and silver through inefficient processing methods. The owners did this to generate as much hype over new discoveries as possible, causing share prices to soar in a speculative bubble.

Then, when the prices peaked, the owners would unload shares on the market and reap a fortune, and then earn even more money when the price began to drop, through a process known as short selling. During one run-up of prices in 1872, the share price of the Belcher mine rose from $300 to $1,575 before crashing back to $108, all in the span of eight months.

Ordinary investors often lost the most money when the mines were the most productive, as speculative mania drove prices so high that no amount of gold or silver recovered could have justified the absurd prices paid for shares. Even when the investors were lucky enough to receive dividends from their shares, many used the money to buy more stock, setting themselves up for even bigger losses when the stock tanked.

HIGH TIMES

So why did investors continue to buy shares in the mines year after year? For the same reason that people buy lottery tickets—even if most people are losing, the fortunes made by the handful of winners were so tantalizing that people gladly took the risk. Besides, money can be made in a rising stock market even if the shares aren’t worth what people pay for them. So what if a $1,400 share in a mine is really only worth $140? As long as the investor can find someone willing to pay $1,500 for it, the $100 profit is just as real as if the seller had pulled $100 worth of silver and gold out of the mine. Nobody really minded that the shares weren’t worth their asking prices, at least not as long as prices kept rising.

The cycles of boom and bust continued for nearly 20 years, thanks to the fact that whenever one deposit of valuable ore seemed about to peter out, a new one would be discovered and the process would repeat itself. Sixteen different major discoveries were made over the years—the last one, called the Consolidated Virginia Bonanza, was uncovered at the 1,200-foot level in 1873. At the peak of its output in 1876, the Consolidated Virginia paid out $1,080,000 in dividends per month. But the good times didn’t last for long: When the Consolidated Virginia was excavated down to the 1,650-foot level in 1877, the ore suddenly ran out.

THE END?

Eighteen years and $320 million worth of silver and gold after the first discovery, no one was ready to believe that the Consolidated Virginia might be the end of the Comstock Lode—there had to be another rich deposit of ore somewhere, didn’t there? Over the next decade, the mining companies spent another $40 million dollars sinking shafts as deep as 4,000 feet in search of new strikes. At first the companies paid these expenses by withholding dividends from shareholders. Then they levied “assessments” on shareholders, which were the opposite of dividends: If a shareholder wanted to hang onto his stock, he had to cough up a sum of money for every share he owned. If he refused, his shares reverted back to the company and could be sold to new investors.

Eighteen years and $320 million worth of silver and gold after the first discovery, no one was ready to believe that the Consolidated Virginia might be the end of the Comstock Lode—there had to be another rich deposit of ore somewhere, didn’t there? Over the next decade, the mining companies spent another $40 million dollars sinking shafts as deep as 4,000 feet in search of new strikes. At first the companies paid these expenses by withholding dividends from shareholders. Then they levied “assessments” on shareholders, which were the opposite of dividends: If a shareholder wanted to hang onto his stock, he had to cough up a sum of money for every share he owned. If he refused, his shares reverted back to the company and could be sold to new investors.

The assessment system worked while new—but smaller—deposits were being found on a fairly regular basis, but as the years passed with no new discoveries, investors began to give up hope. Instead of paying their assessments, they surrendered their shares to the mining companies, who had trouble selling them even for the price of the unpaid assessments. Between 1875 and 1881, the total value of all the mining company shares on the Comstock Lode dropped from $300 million to less than $7 million.

PENNY STOCKS

By 1884 shares that had once sold for $1,500 or more were trading for a nickel apiece; even at that price, it was difficult to find buyers. By then the mining companies were so broke that they had trouble raising enough cash to operate the giant water pumps that kept the mines from flooding. One by one they were shut off, and when the last one was shut down in October 1886, the deepest levels of the lode disappeared under the water forever. Some mining companies managed to eke out small profits for another decade by mining low-grade ore close to the surface, but by 1895 even these were played out and the Comstock era came to a close.

FROM BOOMTOWN TO GHOST TOWN

As the mine went, so too went Virginia City. When the mining jobs dried up, the miners left town in search of work elsewhere, and the businesses that had served them for so many years began to close their doors. The newspapers shut down; so did the hospital, the orphanages, and eventually even the schools. As passenger and freight traffic declined to nothing, the railroads ripped up their tracks and used the steel to lay tracks to newer mining towns. Private homes that could not be sold were boarded up and abandoned. In the years to come, it became a common practice for those few residents who stayed behind to buy neighboring homes for back taxes and tear them down for the firewood.

TRADING ONE GAMBLE FOR ANOTHER

Although the Comstock Lode gave up its last high-grade ore more than 130 years ago, the riches it produced encouraged speculators to look for similar riches in other parts of the state. Many discoveries (none of them as impressive as the Comstock Lode) were made, and mining remained an important sector of the Nevada economy into the 1920s. But when the Great Depression sent both the mining and ranching sectors into steep decline, in 1931 the state of Nevada came up with another way to keep money flowing into state coffers: In 1931 they legalized gambling.

At the time, many people thought the measure would be temporary and that gambling would be outlawed again as soon as the economy improved. That wasn’t the case, of course. Today Las Vegas, founded in 1905 on land auctioned by a railroad company, is one of the largest gambling destinations in the world. There are plenty of casinos in Reno, too. (And if you get tired of gambling, Virginia City, which has found new life as a tourist attraction, is only 17 miles away. It receives two million visitors a year.) So if you’ve ever struck it big or lost your shirt in Las Vegas, or Reno, or anyplace else in Nevada, remember: It all started with the Comstock Lode.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Unsinkable Bathroom Reader. Uncle John and his crack staff of writers prove that after more than two decades in the business, they’re still at the top of their game. Who else but Uncle John could tell you about the tapeworm diet, 44 things to do with a coconut, and the history of the Comstock Lode? Uncle John rules the world of information and humor, so get ready to be thoroughly entertained.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Unsinkable Bathroom Reader. Uncle John and his crack staff of writers prove that after more than two decades in the business, they’re still at the top of their game. Who else but Uncle John could tell you about the tapeworm diet, 44 things to do with a coconut, and the history of the Comstock Lode? Uncle John rules the world of information and humor, so get ready to be thoroughly entertained.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

I originally read this story in one of my UNCLE JOHN books, which I share when I am done. However, I needed the details again in preparation for a sermon I will give in a few weeks. Thanks a lot! (But BTW, it is Sierra Nevada, not Sierra NevadaS. A common mistake – one mountain range named the Sierra Nevada. This error usually occurs when people refer to the “Sierras.”) Thanks.

Hello, I once had some silver “fruit” knives appraised by a certified gemologist. The knives are from 1916. The gemologist said to me, “The silver is probably from the Comstock Lode.” I found this interesting because the knives contained silver hallmarks from England. I guess it wasn’t unusual for English silversmiths to use American silver (?) Do you know if this practice is commonplace? Why would the gemologist say this to me so quickly? Thanks for any info! I don’t know how anyone can trace these knives to the Comstock lode but it might be a nice thing for me the investigate.

According to the book, Bonanza King, a fair amount of the early silver and gold from the Comstock was shipped via San Francisco to Europe.

While much of this essay is accurate, the estimates of dollars in the 1870s and what they are worth in today’s dollars are wildly off base. For instance, 320 million in 1876 is equivalent to 6.4 billion today (or about 20 times the dollar value in 1876), but certainly not the 400 to 480 BILLION as stated in the article. Also, $10,000,000.00 in 1865 is equivalent to no more than 200 million today, not the 14 billion as stated.