The King of the Dudes

If we learned anything from the excellent Bill and Ted movies, it’s that the word “dude” is a remarkably versatile utterance that can either be used to refer to any male acquaintance or as a general vocalisation of surprise or confusion. Go back a hundred years or so to the 1800s and the word dude could actually roughly be understood to mean “a male who dressed in an extremely flamboyant or otherwise eccentric fashion”. Amongst this subset of fashion-conscious men, one man reigned as the undisputed king for over five decades- Evander Berry Wall.

If we learned anything from the excellent Bill and Ted movies, it’s that the word “dude” is a remarkably versatile utterance that can either be used to refer to any male acquaintance or as a general vocalisation of surprise or confusion. Go back a hundred years or so to the 1800s and the word dude could actually roughly be understood to mean “a male who dressed in an extremely flamboyant or otherwise eccentric fashion”. Amongst this subset of fashion-conscious men, one man reigned as the undisputed king for over five decades- Evander Berry Wall.

Roughly being analogous to the earlier and more British-centric term “dandy”, which referred to foppish men who spent exorbitant sums of money on their appearance, American dudes were similarly known in high society for their constant one-upmanship of each other through dress and for spending unthinkable amounts of money just to prove that they could.

Born in 1860 to a pair of extremely wealthy New Yorkers, Evander’s early life was one of excess, comfort and sloth during which little of note happened. During his early adulthood, he inherited about two million dollars (or about $50 million today), the first million when his father passed away when Evander was 18 and the second when his grandfather passed on when he was 22. This seemingly ensured that the young dandy would never need to work or want for anything his entire life.

A lifelong member of the American Café society, Evander’s time was mostly split between attending parties, drinking and generally loafing around while dressing as garishly as possible. He would usually change outfits at least four times a day, often after each meal, and famously claimed (we can only hope exaggerating) that he never drank anything other than champagne his entire adult life. In regards to the latter, in his memoirs he actually credited the bubbly beverage (along with his refusal to consult with doctors) with helping him live longer, stating that “There are more old drunkards than there are old doctors”.

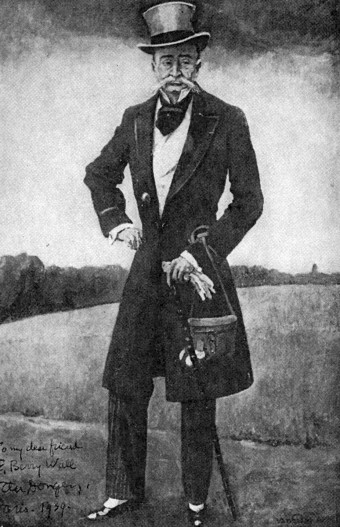

Evander owned a vast wardrobe filled to the brim with a bafflingly wide array of clothing and accessories ranging from long flowing capes to suits made entirely of tweed. He was also a big fan of golden monocles and, all in all at his fashion peak, he was reported to own just over 500 complete sets of clothing plus an abundance of accessories to augment the outfits. One thing that all of his clothes had in common was that they were loud, colorful and, above all, garish.

Evander claimed he cared little about what people thought of his appearance, simply stating that “People should wear what suits them” and would often buck fashion trends by wearing things like purple shoes, yellow flowery waistcoats and gigantic Victorian style stiff collars.

Ironically, the most controversial piece of clothing Evander ever wore was a simple, conservative dinner jacket, sent to him by the legendary Saville row tailor, Henry Poole & Co.. Evander, who was a regular patron to the exclusive store and one of its best customers, was sent a tailless dinner jacket with a personal note from the owners suggesting that it “might be worn for a quiet dinner at home or at an evening’s entertainment at (a) summer resort” in the early 1880s. In typical fashion, Evander decided to instead wear it to a fancy party at the Grand Union Hotel and was immediately thrown out. He later stated that “I was … only readmitted to grace after I had gone to my room and changed into an acceptable evening coat with tails.”

You see, at the time, men in the States were typically required to wear tailcoats at such events. However, over in England, where Poole & Co was based, there had been a recent shift in fashion caused by the Prince of Wales, who in 1860 had taken to wearing a less formal, tailless dinner jacket at private parties. Poole sent an example of this new style of jacket to Evander predicting that it would soon reach the States and presumably wanted him, as one of their most loyal customers, to be the first to own one in America.

Ironically, just a few years after Evander was kicked out of a party for wearing this, the dinner jacket became standard attire at such events. While it isn’t definitive who set the new trend in the States, one James Potter is often given the credit, having met the Prince in 1886, he reportedly decided to get a dinner jacket made by Poole & Co. in a similar style to the Prince’s. When Potter returned to America he began wearing this (at the time) bizarre new garment to parties at a local country club called the Tuxedo Club (named after Tuxedo Park, New York, with the origin of the park’s name being unknown) where it almost immediately caught on with other members. As a result, this new, shorter style of attire ultimately became known worldwide as a “tuxedo”.

While locally well known, Evander came to national attention in 1888 when a newspaper columnist called Blakely Hall began chronicling his extravagant costumes in weekly articles which the public ate up. In fact, the columns were so popular that another journalist began writing almost identical articles about stage actor Robert “Handsome Bob” Hilliard, who like Evander was known for his extravagant dress.

Evander playfully took exception to these articles and the insinuation that there was anyone out there better or more loudly dressed than himself and over the next few months, the two men informally began trying to outdo one another with increasingly outlandish attire in what became known as “the battle of the dudes”. The winner is said to have been crowned when, during the Great Blizzard of 1888, one of the men strolled into the Hoffman House bar wearing gleaming, hip-high leather boots, and the other conceded the contest. Historians don’t seem to able to agree which of the two men donned these boots (and thus won the informal competition). However, according to a contemporary account by the New York Times, it was Evander who wore the boots and won the contest.

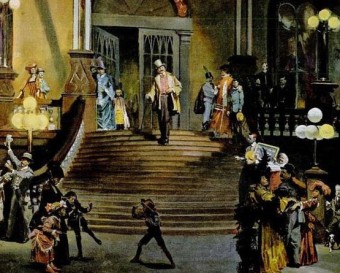

Earlier that same year, Evander first staked his claim to the title of King of the Dudes during an encounter with noted gambler and high roller John “Bet a Million” Gates, in which Gates challenged him to change outfits 40 times in a single day and be seen in public wearing each. This was no small feat given the elaborate getups Evander wore, but with the help of his valet, he nevertheless managed to accomplish the task. During one party alone with Gates, Evander managed to change outfits 39 times and socialized a bit in-between each. Evander’s coup de grâce was arriving later that day at a nearby hotel wearing “faultless evening attire”. Always one to make an entrance, he arranged for the hotel’s orchestra to play a song as he walked in. Not only did newspapers across the United States report the event, but afterward he was given the title “The King of Dudes” by the aforementioned reporter Blakely Hall. Beyond this, he was also given a considerable, though undisclosed, sum from an amused Gates.

Unfortunately for Evander, his extremely extravagant lifestyle combined with a disastrous attempt at increasing his fortune via investing left him pretty much penniless and he ultimately had to declare bankruptcy in 1899. This was not the end, however.

Thanks to some family money keeping him going, he was able to continue on as the King of the Dudes, though uprooting himself and his beloved wife to Paris, lamenting that New York “had become fit only for businessmen”. Not just scraping along, after his mother died, he acquired another sizable fortune which was placed in a trust for him and was enough to keep him fabulously attired, kept in the finest of hotels, and regularly rubbing elbows with the elite of Europe for the rest of his long life.

While clothing undeniably consumed much of his life, he did have one other indulgence worth noting- chow chow dogs, of which he owned several. Evander’s love of his dogs was such that during WW1, he refused to visit England since its quarantine laws would have separated him from his pet for an unacceptable amount of time. He instead kept a residence in Paris where he used his considerable wealth and social connections to aid wounded servicemen.

While clothing undeniably consumed much of his life, he did have one other indulgence worth noting- chow chow dogs, of which he owned several. Evander’s love of his dogs was such that during WW1, he refused to visit England since its quarantine laws would have separated him from his pet for an unacceptable amount of time. He instead kept a residence in Paris where he used his considerable wealth and social connections to aid wounded servicemen.

Like their master, these dogs enjoyed nothing but the best and Evander often dressed them in custom made outfits consisting of gigantic collars and silk ties that were, of course, made in the same style and out of the same fabric as his own. During his later years, Evander could often be found dining at the Ritz with one of his dogs.

After a life of living in the lap of luxury, Evander died in 1940, leaving behind an impressive wardrobe and a mere twelve thousand dollars- all that was left of the three vast inheritances he’d previously received.

After a life of living in the lap of luxury, Evander died in 1940, leaving behind an impressive wardrobe and a mere twelve thousand dollars- all that was left of the three vast inheritances he’d previously received.

In his memoirs, Neither Pest Nor Puritan, Evander summed up life as follows, “…the object of life is to do what you have to do and to do it well. That is the art of living.” Coming from a man who seemingly never had to do anything, this seems an odd conjecture.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- High Heels Were Popular Among Men Before Women

- The Surprisingly Recent Time Period When Boys Wore Pink, Girls Wore Blue, and Both Wore Dresses

- Where The Expression “Dressed to the Nines” Came From

- Why Women Fainted So Much in the 19th Century

- How World War I Helped Popularize the Bra

- Neither Pest Nor Puritan: The Memoirs Of E. Berry Wall

- Our Crowd: The Great Jewish Families of New York

- With Well Dressed Men

- Books: Yankee Dude

- Evander Berry Wall: King of the Dudes

- Saratoga Springs, New York: A Brief History

- Yankee Doodle Dandy: The Life and Times of Tod Sloan

- King of the Dudes

- Etymology Tuxedo

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Quoting from the article:

“If we learned anything from the excellent Bill and Ted movies, it’s that the word ‘dude’ is a remarkably versatile utterance that can either be used to refer to any male acquaintance or as a general vocalisation of surprise or confusion.”

That has not been true for a very long time. The misuse of “dude” to refer to a mere fellow or “guy” — and the ludicrous use of “dude” as an expression “of surprise or confusion” — are relatively recent phenomena. Not many years ago, some Americans (probably in a ghetto setting, the source of many neologisms) apparently got tired of the various already-available options — “man,” “guy,” “chap,” “fellow,” etc. — and erred by beginning to make a generic term out of a word, “dude,” that already had two specific meanings.

In the first three or four decades of my life, I heard the word, “dude,” used in only the following two ways:

(1) to refer to a city dweller who is unfamiliar with life on the range, such as an Easterner visiting the West — especially someone who spends time on a “dude ranch.”

(2) to refer to a man who is very fancy in his dress and demeanor — such as “the Durango Dude,” a character in “Corky and White Shadow,” a serial that appeared on TV’s “Mickey Mouse Club” in the 1950s.

I now grimace every time I hear “dude” used in reference to any ordinary person, and I shudder when I hear, “Dude!” used as an interjection of surprise, disapproval, etc.. [It appears that the latter is a sort of replacement of such interjections as, “(Oh,) Man!” “Man alive!” “(Oh,) Brother!” and “(Oh,) Boy!”]

This sounds like a Tim Burton/Johnny Dep movie…

Hey dude, don’t call me dude.