Bill Haast: The Snakeman Who Was Bitten Nearly 200 Times and Lived to Be 100

Born in Paterson, New Jersey in 1910 to Gustav and Otillia Haast, Bill Haast was interested in snakes since he was 7 years old. This interest turned into something of an obsession during summer trips to Boy Scout camp, beginning when he was 11. The next year Bill suffered his first snake bite from a timber rattlesnake he tried to catch. At the time, Bill was four miles from the camp’s first aid station, so he applied the standard field dressing of the day (making crossed cuts over the fang marks and applying potassium permanganate) and walked back to camp. Although his arm had swollen pretty well before getting back to camp, he ultimately recovered with no long term ill effects.

Born in Paterson, New Jersey in 1910 to Gustav and Otillia Haast, Bill Haast was interested in snakes since he was 7 years old. This interest turned into something of an obsession during summer trips to Boy Scout camp, beginning when he was 11. The next year Bill suffered his first snake bite from a timber rattlesnake he tried to catch. At the time, Bill was four miles from the camp’s first aid station, so he applied the standard field dressing of the day (making crossed cuts over the fang marks and applying potassium permanganate) and walked back to camp. Although his arm had swollen pretty well before getting back to camp, he ultimately recovered with no long term ill effects.

When he returned to camp the following year, he suffered another bite from yet another snake he was trying to catch, this time a large copperhead. Having learned his lesson from the previous year, he was equipped with a snakebite kit and was immediately injected with anti-venom. Despite the early treatment, he was hospitalized for a week after this bite.

Not satisfied with snakes in the wild, Bill began collecting them via mail order catalogs as well. When he brought his first one home, he later stated his terrified mother refused to be near it and fled the apartment for three days, initially refusing to come back until he got rid of the snakes. Soon, however, she agreed he could keep, and even grow, his little collection of snakes.

Not satisfied with snakes in the wild, Bill began collecting them via mail order catalogs as well. When he brought his first one home, he later stated his terrified mother refused to be near it and fled the apartment for three days, initially refusing to come back until he got rid of the snakes. Soon, however, she agreed he could keep, and even grow, his little collection of snakes.

Restless and confident, Bill spent his final year in high school sneaking out of the building the second his mom was out of sight after dropping him off. He’d then simply wander around all day. By age 16 in the late 1920s, he gave up the ruse and joined a roadside snake show, hoping to make his way to Florida after reading in a catalog that the diamondback rattle snake he purchased was shipped out of Florida.

After the traveling snake show shut down due to the effects of the Great Depression, he eventually did indeed make his way to the Florida Everglades, where he supported himself by rooming with and helping a bootlegger. While this gave him ample time and opportunity to catch and study various snakes, ultimately the bootlegging entrepreneur was arrested. At this point, Bill had a dream- to start a snake farm. Unfortunately for him, that required money. So he decided to go back to school where he studied to become an airplane mechanic.

Upon graduation, he was hired by Pan Am as a flight engineer and traveled the world, allowing him to collect even more exotic snakes. He generally brought his snakes back via safely storing them away in his toolbox. He stated of this, “In those days there were no laws prohibiting it, but the crew members didn’t appreciate it.”

Besides collecting often deadly snakes from around the world and bringing them on planes back home, Bill also spent his time as a flight engineer saving up money to build a large snake farm. By 1946, he was able to purchase a plot of land in south Miami, sold his house, and began building his Serpentarium.

Unfortunately for him, his wife, Ann, didn’t exactly appreciate his obsession with snakes nor the new direction her husband was taking with his life, and she soon divorced him.

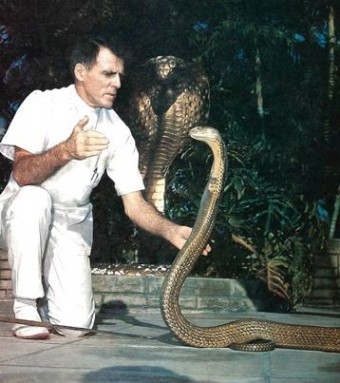

Undeterred, one year later Bill opened the Serpentarium with a skeleton staff of himself, his new wife, Clarita, who was much more supportive of his little snake enterprise, and his son, Bill Jr., who, after being bitten four times by the snakes, left the snake farm to seek safer work.

Over the next 20 years, Bill amassed an impressive array of venomous snakes from around the world, at any given time having in excess of 500 snakes on his little farm. You might think such an endeavor wouldn’t be very profitable, but Bill found ways to make quite a bit of money off his snake farm. He generated income in two ways. First, he “milked” venom from his 60 species of snakes in front of a paying audience every day. This not only generated revenue from ticket sales, but also from the sale of the raw material needed to produce anti-venom- a gram of which would net as much as $5,000 in some cases, taking 100 or so milkings to produce one gram.

Over the next 20 years, Bill amassed an impressive array of venomous snakes from around the world, at any given time having in excess of 500 snakes on his little farm. You might think such an endeavor wouldn’t be very profitable, but Bill found ways to make quite a bit of money off his snake farm. He generated income in two ways. First, he “milked” venom from his 60 species of snakes in front of a paying audience every day. This not only generated revenue from ticket sales, but also from the sale of the raw material needed to produce anti-venom- a gram of which would net as much as $5,000 in some cases, taking 100 or so milkings to produce one gram.

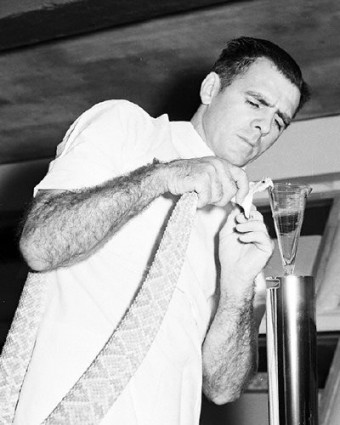

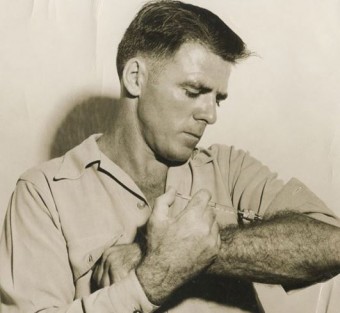

Being something of a dangerous profession with accidental bites not uncommon, Bill also decided to try to use the mithridatism approach to protecting himself against the snakes- namely, injecting himself with gradually increasing doses of venom from different snakes he milked regularly, including the Cape, King and Indian cobras.

This worked. In the 1950s, although he was bitten by cobras approximately 20 times, he had few ill-effects and didn’t need any anti-venom. Eventually, his immunity to many snake bites had grown so strong that he often donated blood to treat snakebite victims when anti-venom for a particular type of venom was not otherwise available. According to the New York Times, over 20 people who likely would have died without the antibodies in his blood were saved because of his donations, including in one instance where Bill flew all the way to Venezuela to donate a pint of his blood to be used for a boy who’d been bitten. For this act, the Venezuelan government made Bill an honorary citizen of the country. (Normally snake anti-venom is made via injecting diluted venom into certain mammals and then collecting the resulting antibodies from the animal’s blood.)

This worked. In the 1950s, although he was bitten by cobras approximately 20 times, he had few ill-effects and didn’t need any anti-venom. Eventually, his immunity to many snake bites had grown so strong that he often donated blood to treat snakebite victims when anti-venom for a particular type of venom was not otherwise available. According to the New York Times, over 20 people who likely would have died without the antibodies in his blood were saved because of his donations, including in one instance where Bill flew all the way to Venezuela to donate a pint of his blood to be used for a boy who’d been bitten. For this act, the Venezuelan government made Bill an honorary citizen of the country. (Normally snake anti-venom is made via injecting diluted venom into certain mammals and then collecting the resulting antibodies from the animal’s blood.)

While the farm was very profitable for Bill, a non-snake-related tragedy led to the closing of the Serpentarium. You see, in addition to snakes, Bill also kept alligators and crocodiles in a pit on the premises. In the late 1970s, a six-year-old boy fell into the pit. Seeing a tasty snack, one of the crocodiles lunged for the boy before a random bystander, Nicolas Caulineau and the boy’s father, could get to him. The two men did eventually manage to get on top of the near one ton crocodile and attempted to free the boy, but it was too late.

While the farm was very profitable for Bill, a non-snake-related tragedy led to the closing of the Serpentarium. You see, in addition to snakes, Bill also kept alligators and crocodiles in a pit on the premises. In the late 1970s, a six-year-old boy fell into the pit. Seeing a tasty snack, one of the crocodiles lunged for the boy before a random bystander, Nicolas Caulineau and the boy’s father, could get to him. The two men did eventually manage to get on top of the near one ton crocodile and attempted to free the boy, but it was too late.

While today Bill would have been sued into oblivion for this, the boy’s parents did not blame Bill for the accident. Nevertheless, he never forgave himself and not long after closed the snake farm… but not before firing nine rounds from his Luger pistol into the crocodile in question, ultimately resulting in it dying about an hour after being shot.

Years earlier, Bill developed a keen interest in the medicinal uses of snake venom when he and a University of Miami researcher experimented with its utility in treating polio, with encouraging results, before Dr. Jonas Salk came up with an effective and safe vaccine against the disease.

Now without his snake farm to run, Bill decided to devote his time to once again exploring various snake venoms’ medicinal properties with medical professionals. This culminated in Bill and a Miami doctor treating over 6,000 patients suffering from multiple sclerosis and arthritis with a certain blend of snake venom. While some of their research and results were promising, in 1980, the FDA shut the pair down, claiming that Bill’s manufacturing process on the venom used for injections was not rigorous enough.

Undeterred, in 1990 Bill persisted with his research at the Miami Serpentarium Laboratories he established. Bill also continued to inject himself with a variety of venoms, which ultimately came from 32 different snake species. Although he had long thought that his daily venom regimen contributed to his good health, a sample size of one certainly isn’t good enough to give definitive credit to anything. When he reached 100 years old, he was asked about this, stating, “Aging is hard. Sometimes, you feel useless. But I always felt I would live this long. It was intuitive. I always told people I’d live past 100, and I still feel I will. Is it the venom? I don’t know.”

Bill Haast died of natural causes some six months after turning 100, on June 15, 2011. In his lifetime, he stated he had been bitten by snakes approximately 173 times, 20 of which were nearly fatal.

Among the more notable of these strikes, he had a rather nasty incident with an eastern diamondback rattlesnake that left one of his hands looking a bit like a claw. In another significant strike, a Malayan pit viper managed to cause significant damage to his index finger. In yet another instance, a cottonmouth snake sank its fangs into one of his fingers, resulting in the finger turning black almost instantly. Concerned, he called his wife over and had her lop off the blackened bit of his fingertip with garden clippers before the venom could spread.

In an incident in 1989, a particularly nasty strike from a Pakistani pit viper nearly killed him, but according to The Associated Press, someone in the White House managed to use one of their contacts in Iran to get rare vials of the anti-venom from that country to Bill, who ultimately recovered.

Despite his love for snakes, he did note that they don’t make the best pets, “You could have a snake for 30 years and the second you leave his cage door cracked, he’s gone. And they’ll never come to you unless you’re holding a mouse in your teeth.”

When asked about his thoughts on life, having lived to over 100, he stated, “The art of living is not an instinct; it must be learned. Isn’t it a pity that it takes all of it before we know how to use that which we no longer have?”

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Truth About Snakebites and Sucking Out the Venom

- Why Don’t Snakes Get Sunburned?

- The Man Who Saved Over Two Million Lives via a Genetic Quirk

- The Man Who was a Dwarf and Later a Giant

- The Blind Man Who Invented Cruise Control

Bonus Facts:

- In the same way we use otherwise poisonous substances from plants as drugs (think: digitalis, opium, hemlock and mandrake), researchers are now popularly exploring the medicinal power of venom. In fact, in recent years scientists have become hopeful that a protein found in the venom of the Asian sand viper that stops blood from clotting, eristostatin, may be effective in helping the body’s immune system fight malignant melanomas. In addition, another protein found in the venom of South American rattlesnakes, crotoxin, is also being tested for its efficacy in fighting certain tumors.

- It should be noted that snakes aren’t nearly as dangerous on the whole as many people give them credit for. For one thing, even the most aggressive of snakes will typically avoid attacking humans if they can help it, unless they feel cornered, and even then they’ll usually give warning before striking. On top of that, around 80% of snakes aren’t significantly harmful to humans, even if they do bite you. Even those that are deadly, most will occasionally not inject venom into you when they strike, simply wanting you to leave. The exact percentage of “dry bites” varies from venomous snake to venomous snake, but, for instance, around 50% of Coral Snake bites are dry bites, delivering no venom.

- Only 9-15 people per year in the U.S. die from snake bites out of about 8000 bites from venomous snakes per year. This means you are about nine times more likely to die from being struck by lightning than die from being bitten by a snake in the United States. Even in Australia where seemingly everything in nature seems capable of killing humans and where 7 out of the world’s 10 deadliest snakes live, there is only about 1 death by a snake bite per year. In both the U.S. and Australia, this is less than are killed annually by bee and wasp stings.

- Rattlesnakes are able to make a rattling noise because their tails are comprised of 6-10 layers of scales. When these layers of scales are shaken, they rattle.

- The Calabar Ground Boa has an equally interesting trait. Their tail actually looks very similar to their head. When they coil up, they hide their real head and leave their fake “head” on their tail exposed. When a predator tries to grab or bite the fake head or is otherwise paying close attention to this fake head, they strike with their real one.

- Another interesting trait in a snake is found in the Dasypeltis Scabra (also called an “Egg Eater”). This snake has special vertebrae that first puncture the egg (after it’s been swallowed and begins passing through the snake) and then other bones in the vertebral column hold the egg so that it doesn’t go too far into the snake. Finally, more specialized vertebrae crush the egg. Once this is accomplished, rather than processing the shell, the snake regurgitates it.

- While in most places, the annual death rate from snake bites is fairly low, in India, around 50,000 people per year are killed by snake bites (out of about 250,000 bites annually). As you might infer from this, a good percentage of Indians don’t have access to anti-venom. Given that there are more homeless people in India than the entire population of the United States and that it is this group that is likely suffering the most bites, this isn’t surprising.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

A snake is not recommended pet, because a snake is a snake and it will remain a snake. Not like tamed pets, a snake don’t see anyone as his master and will not hesitate to bite anyone even eat if not fed properly. Ouch.