Who Invented the Shopping Mall?

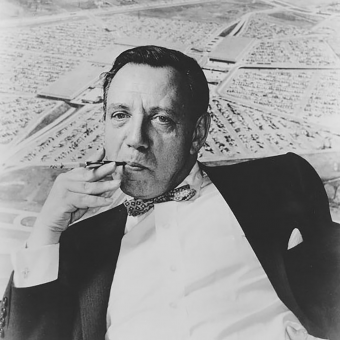

Modern shopping malls are so common that we forget they’ve only been around for about a half century. Here’s the story of how they came to be…and the story of the man who invented them, Victor Gruen—the most famous architect you’ve never heard of.

Modern shopping malls are so common that we forget they’ve only been around for about a half century. Here’s the story of how they came to be…and the story of the man who invented them, Victor Gruen—the most famous architect you’ve never heard of.

FATEFUL LAYOVER

In the winter of 1948, an architect named Victor Gruen got stranded in Detroit, Michigan, after his flight was cancelled due to a storm. Gruen made his living designing department stores, and rather than sit in the airport or in a hotel room, he paid a visit to Detroit’s landmark Hudson’s department store and asked the store’s architect to show him around. The Hudson’s building was nice enough; the company prided itself on being one of the finest department stores in the entire Midwest. But downtown Detroit itself was pretty run-down, which was not unusual for an American city in that era. World War I (1914–18), followed by the Great Depression and then World War II (1939–45), had disrupted the economic life of the country, and decades of neglect of downtown areas had taken their toll.

STRIP JOINTS

The suburbs were even shabbier, as Gruen saw when he took a ride in the country and drove past ugly retail and commercial developments that seemed to blight every town.

The combination of dirt-cheap land, lax zoning laws, and rampant real estate speculation had spawned an era of unregulated and shoddy commercial development in the suburbs. Speculators threw up cheap, (supposedly) temporary buildings derisively known as “taxpayers” because the crummy eyesores barely rented for enough money to cover the property taxes on the lot. That was their purpose: Land speculators were only interested in covering their costs until the property rose in value and could be unloaded for a profit. Then the new owner could tear down the taxpayer and build something more substantial on the lot. But if the proliferation of crumbling storefronts, gas stations, diners, and fleabag hotels were any guide, few taxpayers were ever torn down.

The unchecked growth in the suburbs was a problem for downtown department stores like Hudson’s, because their customers were moving there, too. Buying a house in suburbia was cheaper than renting an apartment downtown, and thanks to the G.I. Bill, World War II veterans could buy them with no money down.

Once these folks moved out to the suburbs, few of them wanted to return to the city to do their shopping. The smaller stores in suburban retail strips left a lot to be desired, but they were closer to home and parking was much easier than downtown, where a shopper might circle the block for a half hour or more before a parking space on the street finally opened up.

Stores like Hudson’s had made the situation worse by using their substantial political clout to block other department stores from building downtown. Newcomers such as Sears and J. C. Penney had been forced to build their stores in less desirable locations outside the city, but this disadvantage turned into an advantage when the migration to the suburbs began.

As he drove through the suburbs, Gruen envisioned a day when suburban retailers would completely surround the downtown department stores and drive them out of business.

SHOPPING AROUND

When Gruen returned home to New York City, he wrote a letter to the president of Hudson’s explaining that if the customers were moving out to the suburbs, Hudson’s should as well. For years Hudson’s had resisted opening branch stores outside the city. It had an image of exclusivity to protect, and opening stores in seedy commercial strips was no way to do that. But it was clear that something had to be done, and as Hudson’s president, Oscar Webber, read Gruen’s letter, he realized that here was a man who might be able to help. He offered Gruen a job as a real estate consultant, and soon Gruen was back driving around Detroit suburbs looking for a commercial strip worthy of the Hudson’s name.

The only problem: There weren’t any. Every retail development Gruen looked at was flawed in one way or another. Either it was too tacky even to be considered, or it was too close to downtown and risked stealing sales from the flagship store. Gruen recommended that the company develop a commercial property of its own. Doing so, he argued, offered a lot of advantages: Hudson’s wouldn’t have to rely on a disinterested landlord to maintain the property in keeping with Hudson’s image. And because Gruen proposed building an entire shopping center, one that would include other tenants, Hudson’s would be able to pick and choose which businesses moved in nearby.

Furthermore, by building a shopping center, Hudson’s would diversify its business beyond retailing into real estate development and commercial property management. And there was a bonus, Gruen argued: By concentrating a large number of stores in a single development, the shopping center would prevent ugly suburban sprawl. The competition that a well-designed, well-run shopping center presented, he reasoned, would discourage other businesses from locating nearby, helping to preserve open spaces in the process.

FOUR OF A KIND

Oscar Webber was impressed enough with Gruen’s proposal that he hired the architect to create a 20-year plan for the company’s growth. Gruen spent the next three weeks sneaking around the Detroit suburbs collecting data for his plan. Then he used the information to write up a proposal that called for developing not one but four shopping centers, to be named Northland, Eastland, Southland, and Westland Centers, each in a different suburb of Detroit. Gruen recommended that the company locate its shopping centers on the outer fringes of existing suburbs, where the land was cheapest and the potential for growth was greatest as the suburbs continued to expand out from downtown Detroit.

Hudson’s approved the plans and quietly began buying up land for the shopping centers. It hired Gruen to design them, even though he’d only designed two shopping centers before and neither was actually built. On June 4, 1950, Hudson’s announced its plan to build Eastland Center, the first of the four projects scheduled for development.

Three weeks later, on June 25, 1950, the North Korean People’s Army rolled across the 38th parallel that served as the border between North and South Korea. The Korean War had begun.

WORST-LAID PLANS

Though Victor Gruen is credited with being the “father of the mall,” he owes a lot to the North Korean Communists for helping him get his temples of consumerism off the ground. He owes the Commies (and so do you, if you like going to the mall) because as Gruen himself would later admit, his earliest design for the proposed Eastland Center was terrible. Had the Korean War not put the brakes on all nonessential construction projects, Eastland might have been built as Gruen originally designed it, before he could develop his ideas further.

Those early plans called for a jumble of nine detached buildings organized around a big oval parking lot. The parking lot was split in two by a sunken four-lane roadway, and if pedestrians wanted to cross from one half of the shopping center to the other, the only way to get over the moat-like roadway was by means of a scrawny footbridge that was 300 feet long. How many shoppers would even have bothered to cross over to the other side?

Had Eastland Center been built according to Gruen’s early plans, it almost certainly would have been a financial disaster. Even if it didn’t bankrupt Hudson’s, it probably would have forced the company to scrap its plans for Northland, Westland, and Southland Centers. Other developers would have taken note, and the shopping mall as we know it might never have come to be.

ALL IN A ROW

Shopping centers of the size of Eastland Center were such a new concept that no architect had figured out how to build them well. Until now, most shopping centers consisted of a small number of stores in a single strip facing the street, set back far enough to allow room for parking spaces in front of the stores. Some larger developments had two parallel strips of stores, with the storefronts facing inward toward each other across an area of landscaped grass called a “mall.” That’s how shopping malls got their name.

There had been a few attempts to build even larger shopping centers, but nearly all had lost money. In 1951 a development called Shoppers’ World opened outside of Boston. It had more than 40 stores on two levels and was anchored by a department store at the south end of the mall. But the smaller stores had struggled from the day the shopping center opened, and when they failed they took the entire shopping center (and the developer, who filed for bankruptcy) down with them.

INSIDE OUT

Gruen needed more time to think through his ideas, and when the Korean War pushed the Eastland project off into the indefinite future, he got it. Hudson’s eventually decided to build Northland first, and by the time Gruen started working on those plans in 1951, his thoughts on what a shopping center should look like had changed completely. The question of where to put all the parking spaces (Northland would have more than 8,000) was one problem. Gruen eventually decided that it made more sense to put the parking spaces around the shopping center, instead of putting the shopping center around the parking spaces, as his original plans for Eastland Center had called for.

WALK THIS WAY

Gruen then put the Hudson’s department store right in the middle of the development, surrounded on three sides by the smaller stores that made up the rest of the shopping center. Out beyond these smaller stores was the parking lot, which meant that the only way to get from the parking lot to Hudson’s—the shopping center’s biggest draw—was by walking past the smaller shops.

This may not sound like a very important detail, but it turned out to be key to the mall’s success. Forcing all that foot traffic past the smaller shops—increasing their business in the process—was the thing that made the small stores financially viable. Northland Center was going to have nearly 100 small stores; they all needed to be successful for the shopping center itself to succeed.

SUBURBAN OUTFITTER

Northland was an outdoor shopping center, with nearly everything a modern enclosed mall has…except the roof. Another feature that set it apart from other shopping centers of the era, besides its layout, its massive scale, and the large number of stores in the development, were the bustling public spaces between the rows of stores. In the past developers who had incorporated grassy malls into their shopping centers did so with the intention of giving the projects a rural, almost sleepy feel, similar to a village green.

Gruen, a native of Vienna, Austria, thought just the opposite was needed. He wanted his public spaces to blend with the shops to create a lively (and admittedly idealized) urban feel, just like he remembered from downtown Vienna, with its busy outdoor cafés and shops. He divided the spaces between Hudson’s and the other stores into separate and very distinct areas, giving them names like Peacock Terrace, Great Lakes Court, and Community Lane. He filled them with landscaping, fountains, artwork, covered walkways, and plenty of park benches to encourage people to put the spaces to use.

NOVELTY STORES

If Northland Center were to open its doors today, it would be remarkably unremarkable. There are dozens, if not hundreds, of similarly-sized malls all over the United States. But when Northland opened in the spring of 1954, it was one-of-a-kind, easily the largest shopping center on Earth, both in terms of square footage and the number of stores in the facility. The Wall Street Journal dispatched a reporter to cover the grand opening. So did Time and Newsweek, and many other newspapers and magazines. In the first weeks that the Northland Center was open, an estimated 40,000-50,000 people passed through its doors each day.

DON’T LOOK NOW

It was an impressive start, but Hudson’s executives still worried. Did all these people really come to shop, or just look around? Would they ever be back? No one knew for sure if the public would even feel comfortable in such a huge facility. People were used to shopping in one store, not having to choose from nearly 100. And there was a very real fear that for many shoppers, finding their way back to their car in the largest parking lot they had ever parked in would be too great a strain and they’d never come back. Even worse, what if Northland Center was too good? What if the public enjoyed the public spaces so much that they never bothered to go inside the stores? With a price tag of nearly $25 million, the equivalent of more than $200 million today, Northland Center was one of the most expensive retail developments in history, and nobody even knew if it would work.

CHA-CHING!

Whatever fears the Hudson’s executives had about making back their $25 million investment evaporated when their own store’s sales exceeded forecasts by 30 percent. The numbers for the smaller stores were good, too, and they stayed good month after month. In its first year in business Northland Center grossed $88 million, making it one of the most profitable shopping centers in the United States. And all of the press coverage generated by the construction of Northland Center made Gruen’s reputation. Before the center was even finished, he received the commission of a lifetime: Dayton’s department store hired him to design not just the world’s first enclosed shopping mall but an entire planned community around it, on a giant 463-acre plot in a suburb of Minneapolis.

NUMBER TWO

Southdale Center, the mall that Victor Gruen designed for Dayton’s department store in the town of Edina, Minnesota, outside of Minneapolis, was only his second shopping center. But it was the very first fully enclosed, climate-controlled shopping mall in history, and it had many of the features that are still found in modern malls today.

It was “anchored” by two major department stores, Dayton’s and Donaldson’s, which were located at opposite ends of the mall in order to generate foot traffic past the smaller shops in between. Southdale also had a giant interior atrium called the “Garden Court of Perpetual Spring” in the center of the mall. The atrium was as long as a city block and had a soaring ceiling that was five stories tall at its highest point.

Just as he had with the public spaces at Northland, Gruen intended the garden court to be a bustling space with an idealized downtown feel. He filled it with sculptures, murals, a newsstand, a tobacconist, and a Woolworth’s “sidewalk” café. Skylights in the ceiling of the atrium flooded the garden court with natural light; crisscrossing escalators and second story skybridges helped create an atmosphere of continuous movement while also attracting shoppers’ attention to the stores on the second level.

GARDEN VARIETY

The mall was climate controlled to keep it at a constant spring-like temperature (hence the “perpetual spring” theme) that would keep people shopping all year round. In the past shopping had always been a seasonal activity in harsh climates like Minnesota’s, where frigid winters could keep shoppers away from stores for months. Not so at Southdale, and Gruen emphasized the point by filling the garden court with orchids and other tropical plants, a 42-foot-tall eucalyptus tree, a goldfish pond, and a giant aviary filled with exotic birds. Such things were rare sights indeed in icy Minnesota, and they gave people one more reason to go to the mall.

INTELLIGENT DESIGN

With 10 acres of shopping surrounded by 70 acres of parking, Southdale was a huge development in its day. Even so, it was intended as merely a retail hub for a much larger planned community, spread out over the 463-acre plot acquired by Dayton’s. Just as the Dayton’s and Donaldson’s department stores served as anchors for the Southdale mall, the mall itself would one day serve as the retail anchor for this much larger development, which as Gruen designed it, would include apartment buildings, single-family homes, schools, office buildings, a hospital, landscaped parks with walking paths, and a lake.

The development was Victor Gruen’s response to the ugly, chaotic suburban sprawl that he had detested since his first visit to Michigan back in 1948. He intended it as a brand-new downtown for the suburb, carefully designed to eliminate sprawl while also solving the problems that poor or nonexistent planning had brought to traditional urban centers like Minneapolis. Such places had evolved gradually and haphazardly over many generations instead of following a single, carefully thought-out master plan.

The idea was to build the Southdale Center mall first. Then, if it was a success, Dayton’s would use the profits to develop the rest of the 463 acres in accordance with Gruen’s plan. And Southdale was a success: Though Dayton’s downtown flagship store did lose some business to the mall when it opened in the fall of 1956, the company’s overall sales rose 60 percent, and the other stores in the mall also flourished.

But the profits generated by the mall were never used to bring the rest of Gruen’s plan to fruition. Ironically, it was the very success of the mall that doomed the rest of the plan.

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

Back before the first malls had been built, Gruen and others had assumed that they would cause surrounding land values to drop, or at least not rise very much, on the theory that commercial developers would shy away from building other stores close to such a formidable competitor as a thriving shopping mall. The economic might of the mall, they reasoned, would help to preserve nearby open spaces by making them unsuitable for further commercial development.

But the opposite turned out to be the case. Because shopping malls attracted so much traffic, it soon became clear that it made sense to build other developments nearby. Result: The once dirt-cheap real estate around Southdale began to climb rapidly in value. As it did, Dayton’s executives realized they could make a lot of money selling off their remaining parcels of land—much more quickly, with much less risk—than they could by gradually implementing Gruen’s master plan over many years.

From the beginning Gruen had seen the mall as a solution to sprawl, something that would preserve open spaces, not destroy them. But his “solution” had only made the problem worse—malls turned out to be sprawl magnets, not sprawl killers. Any remaining doubts Gruen had were dispelled in the mid-1960s when he made his first visit to Northland Center since its opening a decade earlier. He was stunned by the number of seedy strip malls and other commercial developments that had grown up right around it.

REVERSAL OF FORTUNE

Victor Gruen, the father of the shopping mall, became one of its most outspoken critics. He tried to remake himself as an urban planner, marketing his services to American cities that wanted to make their downtown areas more mall-like, in order to recapture some of the business lost to malls. He drew up massive, ambitious, and very costly plans for remaking Fort Worth, Rochester, Manhattan, Kalamazoo, and even the Iranian capital city of Tehran. Most of his plans called for banning cars from city centers, confining them to ring roads and giant parking structures circling downtown. Unused roadways and parking spaces in the center would then be redeveloped into parks, walkways, outdoor cafés, and other uses. It’s doubtful that any of these pie-in-the-sky projects were ever really politically or financially viable, and none of them made it off the drawing board.

HOMECOMING

In 1968 Gruen closed his architectural practice and moved back to Vienna…where he discovered that the once thriving downtown shops and cafés, which had inspired him to invent the shopping mall in the first place, were now themselves threatened by a new shopping mall that had opened outside the city.

He spent the remaining years of his life writing articles and giving speeches condemning shopping malls as “gigantic shopping machines” and ugly “land-wasting seas of parking.” He attacked developers for shrinking the public, non-profit-generating spaces to a bare minimum. “I refuse to pay alimony for these bastard developments,” Gruen told a London audience in 1978, in a speech titled “The Sad Story of Shopping Centers.”

Gruen called on the public to oppose the construction of new malls in their communities, but his efforts were largely in vain. At the time of his death in 1980, the United States was in the middle of a 20-year building boom that would see more than 1,000 shopping malls added to the American landscape. And were they ever popular: According to a survey by U.S. News and World Report, by the early 1970s, Americans spent more time at the mall than anyplace else except for home and work.

VICTOR WHO?

Today Victor Gruen is largely a forgotten man, known primarily to architectural historians. That may not be such a bad thing, considering how much he came to despise the creation that gives him his claim to fame.

Gruen does live on, however, in the term “Gruen transfer,” which mall designers use to refer to the moment of disorientation that shoppers who have come to the mall to buy a particular item can experience upon entering the building—the moment in which they are distracted into forgetting their errand and instead begin wandering the mall with glazed eyes and a slowed, almost shuffling gait, impulsively buying any merchandise that strikes their fancy.

FINISHING TOUCHES

Victor Gruen may well be considered the “father of the mall,” but he didn’t remain a doting dad for long. Southdale Center, the world’s first enclosed shopping mall, opened its doors in the fall of 1956, and by 1968 Gruen had turned publicly and vehemently against his creation.

So it would fall to other early mall builders, people such as A. Alfred Taubman, Melvin Simon, and Edward J. DeBartolo Sr., to give the shopping mall its modern, standardized form, by taking what they understood about human nature and applying it to Gruen’s original concept. In the process, they fine-tuned the mall into the highly effective, super-efficient “shopping machines” that have dominated American retailing for nearly half a century.

BACK TO BASICS

These developers saw shopping malls the same way that Gruen did, as idealized versions of downtown shopping districts. Working from that starting point, they set about systematically removing all distractions, annoyances, and other barriers to consumption. Your local mall may not contain all of the following features, but there should be much here that looks familiar:

- It’s a truism among mall developers that most shoppers will only walk about three city blocks—about 1,000 feet—before they begin to feel a need to head back to where they’d started. So 1,000 feet became a standard length for malls.

- Most of the stairs, escalators, and elevators are located at the ends of the mall, not in the center. This is done to encourage shoppers to walk past all the stores on the level they’re on before visiting shops on another level.

- Malls are usually built with shops on two levels, not one or three. This way, if a shopper walks the length of the mall on one level to get to the escalator, then walks the length of the mall on the second level to return to where they started, they’ve walked past every store in the mall and are back where they parked their car. (If there was a third level of shops, a shopper who walked all three levels would finish up at the opposite end of the mall, three city blocks away from where they parked.)

- Another truism among mall developers is that people, like water, tend to flow down more easily than they flow up. Because of this, many malls are designed to encourage people to park and enter the mall on the upper level, not the lower level, on the theory they are more likely to travel down to visit stores on a lower level than travel up to visit stores on a higher level.

THE VISION THING

- Great big openings are designed into the floor that separates the upper level of shops from the lower level. That allows shoppers to see stores on both levels from wherever they happen to be in the mall. The handrails that protect shoppers from falling into the openings are made of glass or otherwise designed so that they don’t obstruct the sight lines to those stores.

- Does your mall’s decor seem dull to you? That’s no accident—the interior of the mall is designed to be aesthetically pleasing but not particularly interesting, so as not to distract shoppers from looking at the merchandise, which is much more important.

- Skylights flood the interiors of malls with natural light, but these skylights are invariably recessed in deep wells to keep direct sunlight from reflecting off of storefront glass, which would create glare and distract shoppers from looking at the merchandise. The wells also contain artificial lighting that comes on late in the day when the natural light begins to fade, to prevent shoppers from receiving a visual cue that it’s time to go home.

A NEIGHBORLY APPROACH

- Great attention is paid to the placement of stores within the mall, something that mall managers refer to as “adjacencies.” The price of merchandise, as well as the type, factors into this equation: There’s not much point in placing a store that sells $200 silk ties next to one that sells $99 men’s suits.

- Likewise, any stores that give off strong smells, like restaurants and hair salons, are kept away from jewelry and other high-end stores. (Would you want to smell cheeseburgers or fried fish while you and your fiancé are picking out your wedding rings?)

- Have you ever bought milk, raw meat, or a gallon of ice cream at the mall? Probably not, and there’s a good reason for it: Malls generally do not lease space to stores that sell perishable goods, because once you buy them you have to take them right home, instead of spending more time shopping at the mall.

- Consumer tastes change over time, and mall operators worry about falling out of fashion with shoppers. Because of this, they keep a close watch on individual store sales. Even if a store in the mall is profitable, if it falls below its “tenant profile,” or average sales per square foot of other stores in the same retail category, the mall operator may refuse to renew its lease. Tenant turnover at a well-managed mall can run as high as 10 percent a year.

HERE, THERE, EVERYWHERE

Malls have been a part of the American landscape for so long now that a little “mall fatigue” is certainly understandable. But like so much of American culture, the concept has been exported to foreign countries, and malls remain very popular around the world, where they are built not just in the suburbs but in urban centers as well. They have achieved the sort of iconic status once reserved for airports, skyscrapers, and large government buildings. They are the kind of buildings created by emerging societies to communicate to the rest of the world, “We have arrived.” If you climb into a taxicab in almost any major city in the world, be it Moscow, Kuala Lumpur, Dubai, or Shanghai, and tell the driver, “Take me to the mall,” he’ll know where to go.

KILL ’EM MALL

America’s love-hate relationship with shopping malls is now more than half a century old, and for as long as it has been fashionable to see malls as unfashionable, people have been predicting their demise. In the 1970s, “category killers” were seen as a threat. Stand-alone stores like Toys “R” Us focused on a single category of goods, offering a greater selection at a lower price than even the biggest stores in the mall couldn’t match. They were soon followed by “power centers,” strip malls anchored by “big box” stores like Walmart, and discount warehouse stores like Costco and Sam’s Club. In the early 1990s, TV shopping posed a threat, only to fizzle out…and be replaced by even stronger competition posed by Internet retailers like Amazon.

By the early 1990s, construction of new malls in the United States had slowed to a crawl, but this had as much to do with rising real estate prices (land in the suburbs wasn’t dirt cheap anymore), the savings and loan crisis (which made construction financing harder to come by), and the fact that most communities that wanted a mall already had one…or two…or more.

Increasing competition from other retailers and bad economic times in recent years have also taken their toll, resulting in declining sales per square foot and rising vacancy rates in malls all over the country. In 2009 General Growth Properties, the nation’s second-largest mall operator, filed for bankruptcy; it was the largest real estate bankruptcy in American history.

FULL CIRCLE

But mall builders and operators keep fighting back, continually reinventing themselves as they try to keep pace with the times. Open-air malls are remade into enclosed malls, and enclosed malls are opened to the fresh air. One strategy tried in Kansas, Georgia, and other areas is to incorporate shopping centers into larger mixed-use developments that include rental apartments, condominiums, office buildings, and other offerings. Legacy Town Center, a 150-acre development in the middle of a 2,700-acre business park north of Dallas, for example, includes 80 outdoor shops and restaurants, 1,500 apartments and townhouses, two office towers, a Marriott Hotel, a landscaped park with hiking trails, and a lake. (Sound familiar?)

In other words, developers are trying to save the mall by finally building them just the way that Victor Gruen wanted to in the first place.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Heavy Duty Bathroom Reader. The big brains at the Bathroom Readers’ Institute have come up with 544 all-new pages full of incredible facts, hilarious articles, and a whole bunch of other ways to, er, pass the time. With topics ranging from history and science to pop culture, wordplay, and modern mythology, Heavy Duty is sure to amaze and entertain the loyal legions of throne sitters.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Heavy Duty Bathroom Reader. The big brains at the Bathroom Readers’ Institute have come up with 544 all-new pages full of incredible facts, hilarious articles, and a whole bunch of other ways to, er, pass the time. With topics ranging from history and science to pop culture, wordplay, and modern mythology, Heavy Duty is sure to amaze and entertain the loyal legions of throne sitters.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Gruen was not the father of the shopping center, but got the idea of a large scale regional centre from John Graham. If you’re interested, see my article on the Northgate Shopping Centre, which opened in 1950, in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, May 1984. Easily available on JSTORS or I can send you a pdf.

I think Temple Hoyne Buell should be in the running as the father of the outdoor shopping mall. His creation, the Cherry Creek Mall in Denver, upscale and still going strong.