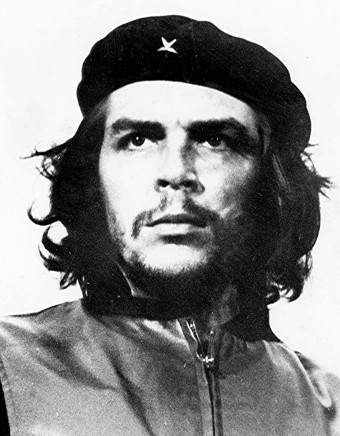

The Death of Che Guevara

On October 9, 1967, controversial Marxist revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara was executed by members of the Bolivian army. Although he was active as a revolutionary for only a relatively short time, Guevara has become one of the most recognizable figures of the 20th century.

On October 9, 1967, controversial Marxist revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara was executed by members of the Bolivian army. Although he was active as a revolutionary for only a relatively short time, Guevara has become one of the most recognizable figures of the 20th century.

Ernesto R. Guevara de la Serna was born in Rosario, Argentina, on June 14, 1928 (though some claim it was really May 14th). After studying medicine in Buenos Aires, he traveled extensively around South America. The injustices he witnessed along the way were the catalyst for what he’d do with the rest of his life.

Guevara was working as a doctor in Mexico City when he met Fidel and Raul Castro. All three went to Cuba to overthrow Fulgencio Batista, whose rule President John F. Kennedy described as, “one of the most bloody and repressive dictatorships in the long history of Latin American repression…”

By 1959, Guevara and the Castro brothers formed a triumvirate of the most powerful men in the Cuban Revolution. Guevara’s first official assignment was at the infamous prison, La Cabaña. His job was to oversee executions and between the years of 1959-1963, hundreds of prisoners met their deaths under his watch. Cuban human rights activist Armando Valladares, who was arrested in 1960 for protesting communism and spent the next 22 years in prison for this, said of Guevara, “He [Guevara] was a man full of hatred … [He] executed dozens and dozens of people who never once stood trial and were never declared guilty … In his own words, he said the following: ‘At the smallest of doubt we must execute.’ And that’s what he did at the Sierra Maestra and the prison of Las Cabanas.”

Valladares went on to state, “For me, it meant 8,000 days of hunger, of systematic beatings, of hard labor, of solitary confinement and solitude, 8,000 days of struggling to prove that I was a human being, 8,000 days of proving that my spirit could triumph over exhaustion and pain, 8,000 days of testing my religious convictions, my faith, of fighting the hate my atheist jailers were trying to instill in me with each bayonet thrust, fighting so that hate would not flourish in my heart, 8,000 days of struggling so that I would not become like them.”

On October 24, 1963, President Kennedy shared his own thoughts on the situation in Cuba in an interview with journalist Jean Daniel (later published in The New Republic on December 14, 1963)

I believe that there is no country in the world, including the African regions, including any and all the countries under colonial domination, where economic colonization, humiliation and exploitation were worse than in Cuba, in part owing to my country’s policies during the Batista regime. I believe that we created, built and manufactured the Castro movement out of whole cloth and without realizing it. I believe that the accumulation of these mistakes has jeopardized all of Latin America. The great aim of the Alliance for Progress is to reverse this unfortunate policy. This is one of the most, if not the most, important problems in America foreign policy. I can assure you that I have understood the Cubans. I approved the proclamation which Fidel Castro made in the Sierra Maestra, when he justifiably called for justice and especially yearned to rid Cuba of corruption. I will go even further: to some extent it is as though Batista was the incarnation of a number of sins on the part of the United States. Now we shall have to pay for those sins. In the matter of the Batista regime, I am in agreement with the first Cuban revolutionaries. That is perfectly clear.

With the revolution successful, matters of actually running the country came to the forefront and, although Guevara lacked any business training, he was eventually named Finance Minister and President of the Cuban national bank. He worked very hard at his post (all other controversies aside, no-one could ever accuse Che of being a slacker) and was very popular with the people, but he failed to produce results, and Cuba’s economy suffered greatly.

Guevara also began to openly question the Soviet Union’s commitment to global socialism, especially after Nikita Khrushchev removed nuclear missiles from Cuba during the 1962 Missile Crisis.

In that era of world revolution, Che Guevara became incredibly famous, even outside of Cuba. But in 1965, he dropped out of sight, and if Castro knew where he was, he wasn’t talking. At least not until that October, when Castro admitted Guevara had resigned his posts and left Cuba “to fight imperialism… in new fields of battle.”

Guevara made his way from the African Congo, back to Cuba, and finally, on the suggestion of Castro, to Bolivia. At first, he and his group of 120 guerrillas had some initial victories. Then a U.S.-trained battalion of Bolivian Rangers began hunting them down.

“Bolivia. July, 1967,” Guevara noted in his diary. “The negative aspects prevail, including the failure to make contact with the outside. We are down to 22 men, three of whom are disabled, including myself.”

Things got even worse by September when Guevara’s life-long asthma flared up, and he was also suffering from dysentery. The Bolivian Rangers were closing in to boot. On October 8, 1967, the Rangers finally got their man. He was executed the next day; his body photographed on a stone slab with the photographic evidence published world-wide to erase any doubt.

Things got even worse by September when Guevara’s life-long asthma flared up, and he was also suffering from dysentery. The Bolivian Rangers were closing in to boot. On October 8, 1967, the Rangers finally got their man. He was executed the next day; his body photographed on a stone slab with the photographic evidence published world-wide to erase any doubt.

Many years after his death, Che Guevara’s role in history is still hotly debated, as are the many seemingly contradictory aspects of his life, such as being a rebellious young man who would state in 1961, “Youth must refrain from ungrateful questioning of Government mandates, instead they must dedicate themselves to study, work, and military service.” Whatever one’s opinion on the man, one thing’s for certain– thanks to Alberto Korda’s photograph of Guevara taken in March of 1960 seen on everything from posters to coffee cups even today, he’s one the most recognizable figures of the 20th century.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Vasili Arkhipov: The Man Who Saved the World

- The Soviet Superman: Red Son

- How Did the Cold War Start and End?

- Why the Viet Cong Were Called “Charlie”

- For Nearly Two Decades the Nuclear Launch Code at all Minuteman Silos in the United States Was 00000000

| Share the Knowledge! |

|