Thor Heyerdahl and the Kon-Tiki

Thor Heyerdahl was born in Larvik, Norway on October 6, 1914. His father worked as a brewer while Heyerdahl’s mother held a leadership position at a local museum. Heyerdahl spent his childhood trekking through the forest at the edge of town and then climbing mountains with his pet husky. Despite those adventures, he only learned to swim in his twenties- nearly drowning twice when he was young led to an understandable fear of water until then.

Thor Heyerdahl was born in Larvik, Norway on October 6, 1914. His father worked as a brewer while Heyerdahl’s mother held a leadership position at a local museum. Heyerdahl spent his childhood trekking through the forest at the edge of town and then climbing mountains with his pet husky. Despite those adventures, he only learned to swim in his twenties- nearly drowning twice when he was young led to an understandable fear of water until then.

After studying geology and zoology at the University of Oslo, Heyerdahl embarked on a yearlong stay (1937-1938) on an island in the South Pacific called Fatu Hiva. The trip served the dual purpose of giving Heyerdahl the opportunity to study the local flora and fauna while also serving as a honeymoon with his new wife, Liv Coucheron Torp Heyerdahl.

A portion of Heyerdahl’s time of Fatu Hiva was spent with local villagers and a conversation with a village elder forever changed his life. The elder told Heyerdahl legends about his ancestors, claiming they came from a land far to the east of the island and their leader was a man named Tiki.

The name Tiki stuck with Heyerdahl. It was similar to the legendary fair skinned Peruvian sun king/god, Con-Tici (aka Viracocha), who ruled over a pre-Incan fair skinned people living near Lake Titicaca in South America. He also saw parallels in the legends from the village elder and the stories told about the fair skinned people being massacred, with the survivors fleeing to the sea.

This and other such tenuous evidence led Heyerdahl to hypothesize that Con-Tiki might very well be who the elder referred to as Tiki and that the rafts and this legendary people of Peru could possibly have survived the trip across the Pacific Ocean. So, in his view, the islands may not have been populated by people from Asia as previously thought, but instead by those from South America.

Heyerdahl met countless objections to his theory from academics and others, and he had difficulty getting his thesis, “Polynesia and America: A Study in Prehistoric Relations,” published. The consensus was that a primitive raft could not withstand the violent storms that frequently occurred in the South Pacific. Plus, there was the question of whether or not humans of this period with the technology at hand could have survived the journey when exposed to the elements for the length of time it would take to get from South America to Polynesia. Thus, the long-held theory stood- that 5,500 years ago or so, people from Asia traveled to Polynesia and gradually settled the islands.

To get around these objections, Heyerdahl decided to put his life on the line to prove it could be done. After scrounging up from various sources a little over $22,000 for the journey, he then went searching for a few people to accompany him, placing an ad stating: “Am going to cross the Pacific on a wooden raft to support a theory that the South Sea islands were peopled from Peru. Will you come? Reply at once.”

To get around these objections, Heyerdahl decided to put his life on the line to prove it could be done. After scrounging up from various sources a little over $22,000 for the journey, he then went searching for a few people to accompany him, placing an ad stating: “Am going to cross the Pacific on a wooden raft to support a theory that the South Sea islands were peopled from Peru. Will you come? Reply at once.”

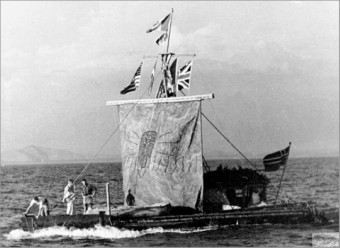

He assembled a team of five men, four fellow Norwegians and a Swede, to sail with him from Peru to Polynesia. Then he flew to Peru where he and his crew painstakingly recreated a raft according to the materials and technology found in pre-Colombian Peru. The resulting raft was fashioned of nine balsawood logs tied together with hemp ropes and a bamboo cabin open at one side for shelter. They christened it “Kon-Tiki.”

Heyerdahl was thirty-two years old when the Kon-Tiki left port on April 28, 1947. He was joined by his five crewmembers, a green parrot, multiple portable radios, a hand crank generator and batteries, 275 gallons of water stored in cans as well as sealed bamboo rods, and various food supplies such as numerous coconuts and sweet potatoes, as well as field rations supplied by the United States military and other implements needed to document the journey.

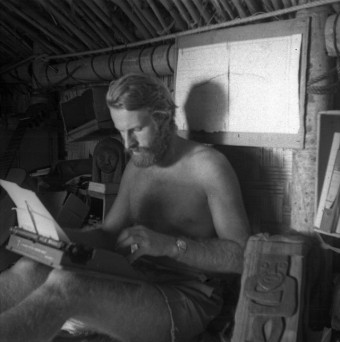

The men spent the next three months battling the dangerous weather and ocean swells, taunting sharks that swam close to their craft, and supplementing their provisions with various fish, which were reportedly, along with the sharks, the explorers’ near constant companions around the boat during the entire journey. They sent regular radio reports back to the mainland on their progress and Heyerdahl filmed sections of their voyage on his camera.

On August 7, 1947, the Kon-Tiki had traveled some 4,300 miles when it finally hit a reef and forced the crew to land on an uninhabited island off of Raroia, in French Polynesia. They spotted shore about a week and 260 miles earlier at Angatau atoll, but were unable to land safely. Nevertheless, one hundred and one days after setting out from Peru, Heyerdahl proved that the nautical technology available to pre-Columbian Peruvians could have successfully brought them to Polynesia.

On August 7, 1947, the Kon-Tiki had traveled some 4,300 miles when it finally hit a reef and forced the crew to land on an uninhabited island off of Raroia, in French Polynesia. They spotted shore about a week and 260 miles earlier at Angatau atoll, but were unable to land safely. Nevertheless, one hundred and one days after setting out from Peru, Heyerdahl proved that the nautical technology available to pre-Columbian Peruvians could have successfully brought them to Polynesia.

Heyerdahl returned to Norway to global fanfare. His footage from the expedition netted him an Oscar in 1951 for Best Documentary Film, and his book titled The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas has been translated into 65 languages and has sold an estimated 20 million copies- the whole thing becoming something of a cultural phenomenon with “Tiki bars,” “Tiki shorts,” “Tiki Torches,” etc. popping up, as well as the famous “Tiki Room” in Disneyland.

But, as you might imagine would happen when a husband decides to take an extremely dangerous several month jaunt across the big blue without his wife, his personal life suffered irrecoverable damage, and he and Liv got divorced in 1948. One of their sons later claimed of this that his mother had felt betrayed because, when they got married, it was supposedly with the understanding that she would be a partner in Heyerdahl’s research and exploration, but ultimately that promise was never fulfilled. He also stated, “My father couldn’t cope with her being such a strong, independent woman. His idea of the perfect female was a Japanese geisha, and my mother was no geisha.”

Of course, proving that something could be done and proving that it was done are two different things and Heyerdahl’s theory was still not well accepted. Potential evidence cited against his idea included differences in the language and cultural traits between the people on the islands and those in South America.

Of course, proving that something could be done and proving that it was done are two different things and Heyerdahl’s theory was still not well accepted. Potential evidence cited against his idea included differences in the language and cultural traits between the people on the islands and those in South America.

Heyerdahl died in 2002, not living to see that he, in fact, had the last word… sort of. In 2011, Professor Erik Thorsby of the University of Oslo performed genetic tests on inhabitants of Easter Island. While it is true that the previous idea that the islanders had originally come from Asia did bear out, on the whole, Dr. Thorsby also discovered that at some point DNA that could only have come from Native Americans was also introduced into the population, whether via the islanders making the jaunt across the ocean and back, or from peoples from South America making a one way trip. Further research into the matter showed that the South American component of the DNA in the Rapanui people tested seems to have been introduced around the mid-13th century to the late 15th century. For reference, the particular island in question wasn’t colonized by Polynesians until the early 13th century. So, in the end, genetic evidence seems to suggest that Heyerdahl and the popular opinion were both right, and both wrong.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Why Native Americans Didn’t Wipe Out Europeans With Diseases

- Magellan Was Not the First Person to Circumnavigate the Globe, The Man Who First Did It May Have Been Magellan’s Slave

- The Real Life Indiana Jones: Roy Chapman Andrews

- Did the Warrior Women Known as the Amazons Ever Exist?

- People in Columbus’ Time Did Not Think the World Was Flat

Bonus Facts:

- Thor Heyerdahl also hypothesized that Egyptians may have traveled to the Americas, based upon the building of pyramids in both areas, and had a traditional boat that would have been available to the Egyptians built. After naming the boat after the sun god Ra, Heyerdahl set off with a crew from Morocco for the Americas on May 25, 1969. The ship sank 600 miles short of its goal, but he completed the journey a year later with the Ra II.

- A third expedition in a recreated Mesopotamian-era read ship, named the Tigris, that was meant to sail from the Tigris River to the Red Sea, ended after five months. The North Yemen government refused to let the ship pass, and Heyerdahl burnt the ship in the port of Djibouti in early April 1978.

- Kon-Tiki Sails Again

- Thor Heyerdahl’s epic ocean voyage the stuff of legend, and film

- Thor Heyerdahl

- Kon-Tiki explorer was partially right – Polynesians had South American roots

- Thor Heyerdahl

- Kon-Tiki Trip Ends on Pacific Reef; Party Safe After 4,000-Mile Drift

- Kon-Tiki voyager Thor Heyerdahl dies

- Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki Voyage

- Thor Heyerdahl

- Thor Heyerdahl Dies at 87; His Voyage on Kon-Tiki Argued for Ancient Mariners

- Wayfinders: A Pacific Odyssey

- Chachapoya Culture

- Viracocha

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

This article was very interesting, Sarah. Thank you!