The Great Race

It involved only a half-dozen cars and 17 men, but this was one race that not only made history- it changed it.

It involved only a half-dozen cars and 17 men, but this was one race that not only made history- it changed it.

Get a Horse

In 1908 the promise of the automobile was just that- a promise. The industry was in its infancy, and most people still relied on horses or their own two feet to get from one place to another. Skeptics were convinced that the automobile was just an expensive and unreliable gimmick. So how could anyone prove to the world that the automobile was the most practical, durable, and reliable means of transport ever invented? Easy: Sponsor a race. But not just any race- it would have to be a marathon of global proportions, pitting the newfangled machines (and their drivers) against the toughest conditions possible on a course stretching around the world, with a sizable cash prize to the winner, say, $1,000. Then call it “The Great Race”…and cross your fingers.

My Car’s Better Than Yours

It’s hard to comprehend the hold automobiles had on the public imagination at the turn of the 20th century. A similar frenzy of technological one-upmanship occurred during the race to the moon in the 1960s, as industrial nations competed fiercely to be considered the most modern and up-to-date technologically.

When it came to cars, there had been a few rally-style road races but nothing on a truly global scale. So the New York Times and the French newspaper Le Matin combined to organize a bigger, better competition designed to be the ultimate test of man and machine. Starting in New York City, the racers would cross the continental United States and the Alaskan territory, take a ferry across the Bering Strait, then drive from Vladivostok across Siberia to Paris-a trek of 22,000 miles.

Few paved roads existed anywhere at the time, and much of the planned route crossed vast roadless areas. And with few gas stations in existence, just completing the course would require every ounce of stamina and ingenuity on the part of the car and the driver, but the winner would own indisputable bragging rights to the claim of Best Car in the World.

Gentlemen, Start Your Engines

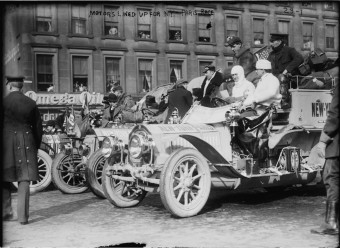

To the cheers of a crowd of 250,000 people, six cars representing four nations pulled out of New York’s Times Square on February 12, 1908, to begin the great adventure. France had three cars: a De Dion-Bouton, a Motobloc, and a Sizaire-Naudin. Germany was represented by a Protos, and Italy by a Zust. All but the American entry- a stock off-the-line Thomas Flyer driven by George Schuster- were custom built for the competition. (The Thomas was a last-minute entry because the sponsors couldn’t bear the thought of a race of this magnitude not having an American representative.) All but the 1-cylinder Sizaire-Naudin had 4 cylinder engines ranging from 30-60 horsepower; the fastest, the Protos, could get up to 70 mph. The cars were heavy, boxy things, with open cockpits and no windshields (glass was considered too dangerous). Each team consisted of a principal driver, a relief driver/mechanic, and an assistant, usually a reporter who would travel with the team and send stories from the road via telegraph.

To the cheers of a crowd of 250,000 people, six cars representing four nations pulled out of New York’s Times Square on February 12, 1908, to begin the great adventure. France had three cars: a De Dion-Bouton, a Motobloc, and a Sizaire-Naudin. Germany was represented by a Protos, and Italy by a Zust. All but the American entry- a stock off-the-line Thomas Flyer driven by George Schuster- were custom built for the competition. (The Thomas was a last-minute entry because the sponsors couldn’t bear the thought of a race of this magnitude not having an American representative.) All but the 1-cylinder Sizaire-Naudin had 4 cylinder engines ranging from 30-60 horsepower; the fastest, the Protos, could get up to 70 mph. The cars were heavy, boxy things, with open cockpits and no windshields (glass was considered too dangerous). Each team consisted of a principal driver, a relief driver/mechanic, and an assistant, usually a reporter who would travel with the team and send stories from the road via telegraph.

They’re Off!

Immediately upon leaving Manhattan, the cars drove into a fierce snowstorm that claimed the Sizaire-Naudin as the race’s first victim. The 15-horspower French two-seater broke down in Peekskill, New York, and was forced to quit. It had gone a mere 44 miles. Snow dogged the remaining cars all the way to Chicago, slowing their progress to a snail’s pace. It took the Thomas Flyer eight hours to travel four miles in Indiana, and then only with horses breaking the trail in front of the car.

Immediately upon leaving Manhattan, the cars drove into a fierce snowstorm that claimed the Sizaire-Naudin as the race’s first victim. The 15-horspower French two-seater broke down in Peekskill, New York, and was forced to quit. It had gone a mere 44 miles. Snow dogged the remaining cars all the way to Chicago, slowing their progress to a snail’s pace. It took the Thomas Flyer eight hours to travel four miles in Indiana, and then only with horses breaking the trail in front of the car.

After Chicago, the cars headed across the Great Plains in sub-zero temperatures. To keep warm, the French Motobloc team rerouted heat from the engine into the cab (an innovation that found its way into future cars) but to no avail: The Motobloc had to quit the race in Iowa. Meanwhile, the winter weather had turned the plains to mud, which stuck to the chassis of the cars, adding hundreds of pounds of weight to each vehicle. Teams took to stopping at fire stations in every town they passed for a high-pressure rinse.

Unable to find usable roads across Nebraska, the drivers took to “riding the rails,” straddling railroad tracks and bouncing along, tie to tie, for hundreds of miles. (Blowouts were frequent.) A Union Pacific conductor rode along with the American team to alert them to oncoming trains. In especially bad weather, one team member would straddle the radiator with a lantern and peer ahead of the car.

When there were no train tracks, the cars used ruts left by covered wagons years before. They navigated by the stars, sextants, compasses, and local guides, when they could hire them. And if they had to stop for more than a few hours, the radiators had to be completely drained- antifreeze hadn’t been invented yet.

Taking the Lead

After 41 days, 8 hours, 15 minutes, the Thomas Flyer was the first entrant to reach San Francisco, becoming the first car ever to cross the United States in winter. The American team promptly boarded a steamer to Valdez, Alaska, the starting spot for the overland trip to the Bering Sea, and brought a crate of homing pigeons with them to send reports back to the States. Race organizers had hoped the ice across the Bering Strait would provide a bridge for the cars. But the Alaska leg had to be scrapped because the weather and driving conditions were even worse than they’d been in the United States. (The pigeon plan didn’t work so well, either. The first bird sent aloft from Valdez was attacked and eaten by seagulls.)

After 41 days, 8 hours, 15 minutes, the Thomas Flyer was the first entrant to reach San Francisco, becoming the first car ever to cross the United States in winter. The American team promptly boarded a steamer to Valdez, Alaska, the starting spot for the overland trip to the Bering Sea, and brought a crate of homing pigeons with them to send reports back to the States. Race organizers had hoped the ice across the Bering Strait would provide a bridge for the cars. But the Alaska leg had to be scrapped because the weather and driving conditions were even worse than they’d been in the United States. (The pigeon plan didn’t work so well, either. The first bird sent aloft from Valdez was attacked and eaten by seagulls.)

The U.S. team was given a 15-day bonus for their Alaskan misadventure and told to return to San Francisco to join the other racers on the S.S. Shawmutt, bound for Yokohama, Japan. At the same time, the German team was penalized 15 days for putting their car on a train from Ogden, Utah, to San Francisco. Both decisions would bear heavily on the race’s end.

Gentlemen, Restart Your Engines

Once they docker in Japan, the remaining competitors had to get their cars to the port of Vladivostok, Russia, where the race would officially resume. The Germans and Italians took another ship; the Americans and the French drove across Japan and took a ferry. It was too much for the De Dion-Bouton. After 7,332 miles, the French team threw in the towel, and only three cars were left: the German Protos, the Italian Zust, and the American Thomas Flyer. After another rousing send-off from a roaring crowd of spectators, the cars zoomed out of Vladivostok… and into the mud. The spring thaw had turned the Siberian tundra into a quagmire.

Only a few miles out of Vladivostok, the American team came upon the German Protos stuck in deep mud. George Schuster carefully nudged his car past the Germans onto firmer ground a few hundred yards ahead. With him were mechanic George Miller, assistant Hans Hansen, and New York Times reporter George Macadam. When Hansen suggested they help the Germans out, the others agreed. The stunned Germans were so grateful that their driver, Lt. Hans Koeppen, uncorked a bottle of champagne he’d been saving for the victory celebration in Paris, declaring the American gesture “a gallant and comradely act.” The two teams raised a glass together, reporter Macadam recorded the moment for his paper, and the subsequent photograph appeared in papers around the globe and became the most enduring image of the race.

Only a few miles out of Vladivostok, the American team came upon the German Protos stuck in deep mud. George Schuster carefully nudged his car past the Germans onto firmer ground a few hundred yards ahead. With him were mechanic George Miller, assistant Hans Hansen, and New York Times reporter George Macadam. When Hansen suggested they help the Germans out, the others agreed. The stunned Germans were so grateful that their driver, Lt. Hans Koeppen, uncorked a bottle of champagne he’d been saving for the victory celebration in Paris, declaring the American gesture “a gallant and comradely act.” The two teams raised a glass together, reporter Macadam recorded the moment for his paper, and the subsequent photograph appeared in papers around the globe and became the most enduring image of the race.

Human Obstacles

Road conditions in Siberia were even worse than they’d been in the western United States. Once again the cars took to the rails- this time on the tracks of the Trans-Siberian Railway. An attempt by Schuster to use a railroad tunnel could have been a scene from a silent-movie comedy, as the American car frantically backed out of the tunnel ahead of an oncoming train. There were other obstacles, too. At one point, the American team was charged by a band of horsemen brandishing rifles. The Americans burst into laughter and drove right through the herd of riders, leaving the bandits in the dust.

Road conditions in Siberia were even worse than they’d been in the western United States. Once again the cars took to the rails- this time on the tracks of the Trans-Siberian Railway. An attempt by Schuster to use a railroad tunnel could have been a scene from a silent-movie comedy, as the American car frantically backed out of the tunnel ahead of an oncoming train. There were other obstacles, too. At one point, the American team was charged by a band of horsemen brandishing rifles. The Americans burst into laughter and drove right through the herd of riders, leaving the bandits in the dust.

Driving around the clock created other problems: The relief driver often fell out of the open car while sleeping, so the team fashioned a buckle and strap to hold him in- the world’s first seat belt. The length and rigor of the race took its toll as well, and tempers flared. At one point an exasperated Schuster threatened to throw Hansen out of the car and off the team. Hansen responded by pulling his pistol and snarling, “Do that and I will put a bullet in you.” Mechanic George Miller drew his gun and snapped, “If any shooting is done, you will not be the only one.” Finally both sides agree to holster their weapons and press on.

Italian Tragedy

By May the cars had been racing around the world for four months. The quicker German Protos had pulled ahead of the American Thomas Flyer, while the underpowered Italian Zust fell farther and father behind but pressed on, convinced that they’d catch up. Then disaster struck. Outside Tauroggen, a Russian frontier town, a horse drawing a cart was startled by the sound of the passing Zust and bolted out of control. A child playing near the road was trampled and killed. The Italians drove into Tauroggen to report the accident and were promptly thrown in jail, where they remained for three days, unable to communicate with anyone outside. Finally, the local police determined the driver of the cart was at fault for losing control of his horse, and released them. They continued on toward Paris in a somber mood.

And the Winner Is…

On July 30, 1908- 169 days after the race’s start- the Thomas Flyer arrived on the outskirts of Paris, smelling victory. The Protos had actually gotten to Paris four days earlier, but because of the Americans’ 15-day bonus and the Germans’ 15-day penalty, everyone knew the American team had an insurmountable margin of victory. Or did they? Before the Americans could enter the city, a gendarme stopped them. French law required automobiles to have two working headlights. The Flyer had only one; the other had been broken back in Russia (by a bird). A crowd gathered. Parisians, like thousands of others around the world, had been following the progress of the Great Race for months in the papers. They were anxious to welcome the victors at the finish line on the Champs-Elysees.

On July 30, 1908- 169 days after the race’s start- the Thomas Flyer arrived on the outskirts of Paris, smelling victory. The Protos had actually gotten to Paris four days earlier, but because of the Americans’ 15-day bonus and the Germans’ 15-day penalty, everyone knew the American team had an insurmountable margin of victory. Or did they? Before the Americans could enter the city, a gendarme stopped them. French law required automobiles to have two working headlights. The Flyer had only one; the other had been broken back in Russia (by a bird). A crowd gathered. Parisians, like thousands of others around the world, had been following the progress of the Great Race for months in the papers. They were anxious to welcome the victors at the finish line on the Champs-Elysees.

Schuster’s crew pleaded with the gendarme, but he wouldn’t budge. No headlight, no entry. A frustrated Schuster was about to set off an international incident by attacking the gendarme when a bicyclist offered the Americans the headlamp from his bike. Mechanic Miller tried to unbolt the light but couldn’t pry it off. The solution: They lifted the bike onto the hood of the car and held it in place by hand. The gendarme shrugged his shoulders and waved them on. A few hours later they crossed the finish line. Victory at last!

A New Era Begins

The celebrations lasted for weeks, long enough for the Italian team, weary but unbowed, to roll into Paris on September 17 and take third place. The Great Race was officially over. The drivers and their crews became national heroes in their home countries. When the Americans got back to New York, they were given a ticker-tape parade down Fifth Avenue and invited by President Theodore Roosevelt (the first U.S. president to drive a car) to a special reception at his summer house on Long Island. Today the Thomas Flyer is on display in Harrah’s Automobile Collection in Reno, Nevada. Munich’s Deutsches Museum has the German Protos. The Italian Zust was destroyed in a fire only months after the race, but the ultimate fates of the cars involved didn’t matter. All three finishers had proved that a car could reliably and safely go anywhere in the world at any time, and under any conditions. No other form of transport could make the same claim. With the conclusion of the Great Race, the Automobile Age had officially arrived. That same year, Henry Ford put the Model T into full production on the assembly line, and the world has been car-crazy ever since.

The celebrations lasted for weeks, long enough for the Italian team, weary but unbowed, to roll into Paris on September 17 and take third place. The Great Race was officially over. The drivers and their crews became national heroes in their home countries. When the Americans got back to New York, they were given a ticker-tape parade down Fifth Avenue and invited by President Theodore Roosevelt (the first U.S. president to drive a car) to a special reception at his summer house on Long Island. Today the Thomas Flyer is on display in Harrah’s Automobile Collection in Reno, Nevada. Munich’s Deutsches Museum has the German Protos. The Italian Zust was destroyed in a fire only months after the race, but the ultimate fates of the cars involved didn’t matter. All three finishers had proved that a car could reliably and safely go anywhere in the world at any time, and under any conditions. No other form of transport could make the same claim. With the conclusion of the Great Race, the Automobile Age had officially arrived. That same year, Henry Ford put the Model T into full production on the assembly line, and the world has been car-crazy ever since.

Postscript

In all the hoopla after the race, the race sponsors “neglected” to hand over the $1,000 prize money to the Thomas Flyer team. It wasn’t until 60 years later, in 1968, that the New York Times awarded the prize money to George Schuster. By then, he was the only member of his team still alive.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Endlessly Engrossing Bathroom Reader. This 22nd edition of the wildly popular Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is jam-packed with their trademark mix of humor and interesting facts. Where else could you learn about the lost cloud people of Peru, the world’s first detective, and the history of surfing?

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Endlessly Engrossing Bathroom Reader. This 22nd edition of the wildly popular Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is jam-packed with their trademark mix of humor and interesting facts. Where else could you learn about the lost cloud people of Peru, the world’s first detective, and the history of surfing?

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

I had read about this race, guess where? The Bathroom reader itself (and other sources over the years). I love the Bathroom reader. I remember buying their first edition as I am one of those that has to read something when sitting on the throne.

I have been known to read the operating instructions of bathroom cleaning products when better reading wasn’t available.

This was obviously the inspiration for the movie “The Great Race”. Great movie. But there was no mention of a pie fight in this article, so that’s probably something they added!

The Thomas Flyer car that won the race was build in Buffalo, NY. Buffalo, at the time, had numerous car companies, many of which were an outgrowth of the bicycle industry there.

Because there were so many rich people in Buffalo who drove cars, they formed a private car club and would drive on Sundays out to a suburb, where they built a gorgeous club house that is still used. This automobile club was just the second one ever established in the US and eventually merged into the AAA.