Why are Electric Wires Color Coded the Way They Are?

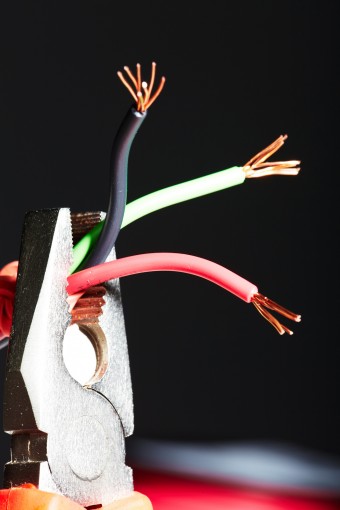

Black, white, green, red, blue, orange, brown and grey, the color of the insulating sheath on an electrical wire generally designates its purpose. So, before you start fiddling around with that new light fixture, besides switching off the breaker to a given circuit, it’s a good idea to determine what the color of each of the wires you’re about to touch means.

Black, white, green, red, blue, orange, brown and grey, the color of the insulating sheath on an electrical wire generally designates its purpose. So, before you start fiddling around with that new light fixture, besides switching off the breaker to a given circuit, it’s a good idea to determine what the color of each of the wires you’re about to touch means.

Residential electricity in the United States didn’t begin with an organized system of color-coded wires, or even a set of standards on how to run them. Since shortly after Thomas Edison first introduced the electric lamp in 1879, the insurance industry began issuing safety guidelines. In fact, the New York Board of Fire Underwriters issued its first set in 1881, addressing capacity, insulation and installation, but not wire color.

By 1882, the National Board of Fire Underwriters (NBFU) had also adopted early safety rules. In 1893, the Underwriters’ National Electric Association, seeking to unify the diverse guidelines established in different locales and standardize electrical installations, came up with the National Code of Rules for Wiring Buildings for Electric Light and Power.

The first National Electrical Code (NEC) was produced by the NBFU in 1897, although it, too, ignored the issue of standardizing wire colors, which wasn’t addressed until the 1928 edition of the NEC. There, a requirement was set to standardize the color of ground wires (called “grounding conductors”), which thereafter were to be either “white or natural gray;” this edition also prohibited the use of these colors for either live or neutral wires.

More in-depth color-coding was introduced in the United States with the 1937 edition of the NEC, where a color-code was established for “multi-branch circuits,” and mandated that three-branch circuits have one each of black, red and white wires; for circuits with even more branches, other colors were added including yellow and blue.

In 1953, the NEC changed its ground color to either green or a bare wire, and the green color was prohibited from use as a circuit wire (i.e., live or neutral).

The color-coding for multi-branches was discarded with the 1971 NEC, although the colors white, natural gray, green and green with yellow stripes were all still reserved, and prohibited for ungrounded wires. The decision to discard the rigid color code requirements for circuit wires was due to the fact that “there are not enough colors to cover the variations in systems and voltages.”

Today in America, ground wires in the United States are to be green, green with a yellow stripe or bare, neutral wires should be white or gray, and circuit wires may be black, red, blue, brown, orange or yellow, depending on the voltage.

Note that these colors are the standard practice in the United States; other countries have instituted different codes (although Canada’s color coding is very similar). For example, Australia and New Zealand have the same colors for ground wires as the United States (green, green with a yellow stripe and bare), although their neutral wires are black or blue; in addition, any color may be used for live wires that isn’t a color used for ground or a neutral wiring, although red and brown are recommended for single phase, and red, white and blue are recommended for multiphase live wires.

The United Kingdom recently (2004) changed its system to comply with that of the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). Although its ground wire color (green with a yellow stripe) remained the same, the color for neutral wires, which formerly was black, should now be blue. Likewise, where an old single-phase line was red, now it should be brown. In addition, the labeling and coloring of multi-phase lines in the UK has also changed: L1, which formerly was red, is now brown, L2 (formerly yellow) is now black, and L3 (formerly blue) is now grey.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Why are There No B Batteries?

- Hollywood Medical Myths: Shocking Someone Who Has “Flat-Lined” Can Get Their Heart Going Again

- How Anti-Static Dryer Sheets Work

- How the Human Body Generates Electricity

- In 1899 Ninety Percent of New York City’s Taxi Cabs Were Electric Vehicles

Bonus Facts:

- In 1894, the Underwriters’ Electrical Bureau branched off from the NBFU, and this organization eventually became Underwriters Laboratories (UL), a non-profit testing laboratory that today certifies that products meet the standards it establishes for safety and performance.

- The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) is also a non-profit, and although it doesn’t (in principle) create standards, it approves and adopts the standards created by other entities (like the UL).

- Of course, with DC circuits, you’ll notice the color coding is different than for AC circuits like you find in the walls of your home. For instance, in the United States, it’s traditional that red is used for the positive side of a negative grounded circuit and black is used for the ground side, along with potentially white as the neutral wire. Why exactly these colors were chosen isn’t known, but some have guessed, at least for the red part of the equation, (pure speculation on their part) that it’s because red is associated with “hot”, thus is commonly used for the so-called hot wire in DC circuits.

- A Colorful History

- Electric Circuits

- Electrically wiring

- History of Fire Protection Engineering

- National Electrical Code (1897)

- National Electrical Code (2014)

- North American Standards

- NEC – History and Purpose

- Some History of Residential Wiring Practices in the U.S.

- UL History

- What is a Circuit?

- Wiring Color Codes

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Why did the IEC change from Red to Brown? And Black to Blue?

And why did so many countries follow suit?

COLOURBLINDNESS – approximately 10% of males suffer from red/green colourblindness(**)

It was regularly found in investigation of electrocution/electric shock cases that red and green were swapped(*) – which is guaranteed to give anyone working on the circuit a bad day.

Switching from Black to Blue helped for two reasons:

1: Some colourblind workers couldn’t tell red and black apart(**) – again resulting in wire swaps being found in the field(*)

2: Having one country/area’s “Neutral” be another country/area’s “Live” is generally a “bad idea”

(*) Wire swaps were most common in cord wiring done by unqualified individuals. Colourblindness is _USUALLY_ detected in an apprentice during training(but not always)

(**) A red/green colourblind driver may not be able to see red _at all_ – the brightest red light/tint ever simply doesn’t register at all, or may be seen as a very dull brown.

This is why red/green are the two WORST POSSIBLE choices for traffic lights. (some countries add blue tint to red lights to help) – which means that a driver claiming not to have seen a red light might actually be telling the truth as few jurisdictions check for colourblindness when testing.

It also means the driver who claimed not to see brake lights ahead might also be telling the truth – particularly as led lamps mean only red gets emitted, whilst red filters over incandescent will usually pass some blue light