The Truth About Ben Franklin’s Epigrams

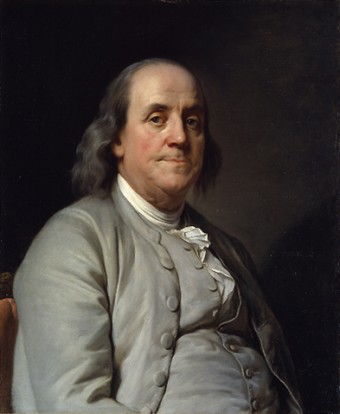

Ben Franklin accomplished a lot of things over his 84 years on Earth. He was an influential newspaper editor and printer. He was an inventor, known for bifocals, the lightening rod, and Franklin stove. He was the governor of Pennsylvania for three years. He was an American founding father, who had a hand in drafting the Declaration of Independence. The biographer Walter Isaacson once called Franklin, “the most accomplished American in his age.” Despite all of this, perhaps the most lasting of all his credits is that of a writer and humorist, the author (or curator, as we will get into in a moment) of many pithy, funny, and true sayings, or epigrams, about life. Here are the origins behind several of them:

Fish and visitors stink in three days

As one might imagine, Ben Franklin didn’t conceive all of these witty epigrams himself. Sometimes he took old ones and adapted them to the times and his voice. “Fish and visitors stink in three days” actually originally comes from the 16th century writer John Lyly. In his most famous work, Euphues – the Anatomy of Wit, he writes, “Fish and guests in three days are stale.” Euphues (from Greek, meaning “graceful and witty”) was such a success when it was published in 1579, that today’s English word “euphemism” is derived from the title of the book Two hundred years later, Franklin would adopt a version of this saying as his own.

You paid too much for that whistle

This underused epigram (at least in this author’s opinion) comes from a 1779 letter he sent to Madame Brillon (long thought to be one of Franklin’s infamous French mistresses). They would correspond twice a week when not in each other’s company, with Franklin usually writing two copies of the same letter – one in English for his safe keeping and one in French for her. This particular letter, published in 1780, became known as “The Whistle” due to a story Franklin recounts from his youth. When Franklin was seven years old, he went to the toy shop and used all his hard-earned money to buy a whistle. While he enjoyed the whistle very much (though the sound annoyed his family), he was made fun of for paying “four times as much for it as it was worth.” He cried, realizing that the amount of money he paid for the whistle was far beyond the pleasure it gave him. Continued Franklin in the letter, “As I grew up, came into the world, and observed the actions of men, I thought I met many who gave too much for the whistle.”

Eat to live, not live to eat

In 1733, Franklin printed the first Poor Richard’s Almanack. Writing under the pseudonym “Poor Richard Saunders,” Franklin dispensed advice, truthisms, and words to live by. In this edition is one of Franklin’s more ironic epigrams – “Eat to live, not live to eat.” This could be called ironic because Franklin was well-known to overindulge in food, wine, and women. He talked of this in his autobiography, saying: “the hard-to-be-governed passion of my youth had hurried me frequently into intrigues with low women that fell in my way.” He fathered a child out of wedlock, flirted and sought company with women half his age and in his autobiography he devoted some time to discussing the advantages of sleeping with older women instead. He was also rumored to be a member of the Medmenham Monks, a group “devoted to sexual access of all kinds”

As for food and drink, he battled gout for much of his elderly life. Once known as “the rich man’s disease,” gout is an arthritic condition that can come from the consumption of too much alcohol, too many foods rich in uric acid (like red meat, seafood, and organ meat), and not enough exercise.

As for the phrase itself, it originally came from the French comedic playwright Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, more known by his stage name Moliere. In his 1668 play, L’Avare, a character says, “to quote an ancient philosopher, one must eat to live, not live to eat.”

Beware of the young doctor & the old barber

Again from the very first Poor Richard’s Almanack in 1733, this saying was probably meant as more of a joke than an actual truth. As one can imagine, this saying doesn’t sit well with doctors nor barbers. In fact, in 1919, New York City coroner (and son of famed physician George F. Shrady Sr.) George Frederick Shrady Jr. wrote as editor of a medical journal that “this (phrase) was true when written, but today the world knows the young physician is the best trained and fears him not. It’s now only true of the barber.” One wonders what the barber would say to that.

Early to bed, early to rise, make a man healthy, wealthy, and wise

This well-known proverb appeared in the 1735 edition of Poor Richard’s Almanack, but, once again, Franklin likely didn’t write it. A form of this phrase appeared in a Renaissance text from the 15th century and even then, it was called old. In a piece about fly fishing, it was used to encourage anglers to go fly fishing early, for it was in the morning sun that fishing was “most profitable.” Said the text, “For it will cause him to be well, also for the increase of his goods, for it will make him rich. As the old English proverb says: ‘Whoever will rise early shall be holy, healthy, and happy.”

There are no gains, without pains

While this exact phrasing may not be familiar to most, this proverb was the inspiration behind the more common workout (and t-shirt) saying, “no pain, no gain.” Printed in the 1734 edition of Poor Richard’s Almanack, Franklin emphasized the phrase “there are no gains, without pains” again in his 1758 self-help book The Way to Wealth.

While some sources date this proverb to 1577 (in the form of “They must take the pain that look for gain.”) and its more modern version to a 1648 Robert Herrick poem, others say this saying may have originated much earlier. The Pirkei Avot (English translation: Chapters of the Fathers) is a collection of rabbinical teachings from the Mishnaic Period, roughly from the first to the third century. According to Chabad.org, in the Pirkei Avot, Ben Hei Hei (a Jewish convert during this time and, apparently, a wise man), stated, “According to the pain is the gain.”

As one can see, Ben Franklin was more of a curator of epigrams, proverbs, and sayings rather than the author, despite that he tends to be given full credit today. Then again, as Franklin once wrote, “any fool can criticize, condemn, and complain – and most fools do.”

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Ben Franklin’s Proposal of Something Like Daylight Saving Time was Written as a Joke

- The Large Number of Human Remains Found In Ben Franklin’s Basement

- 10 Interesting Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Ben Franklin

- The Signers of The Declaration of Independence Did So On August 2nd, 1776 Not July 4th

- You’ve Been Saying It Wrong (11 Famous Quotes That Have Changed Over Time)

Bonus Fact:

- According to Ormand Seavey, editor of Oxford’s edition of Ben Franklin’s autobiography, Thomas Jefferson was chosen over the much more qualified Ben Franklin to write the Declaration of Independence because Franklin was known to put extremely subtle satire in just about everything he wrote and, quite often, it would be so subtle that no one would notice for some time. Knowing this document would likely be examined closely by certain nations of the world, according to Seavey, they chose to avoid the issue by having the much less gifted writer, Jefferson, write the Declaration instead, with Franklin and three others helping Jefferson draft it.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

I liked the last bit, Im no fool tho

“lightening rod”

should be lightning rod

“…too many foods rich in uric acid…”

as well as rich in purines such as dried beans

as I’ve been warned by my doctor.

I would suggest that Euphemism is derived from the Greek ‘Euphemia’ (speak good words) not some book title.

Correct! “Eu-” is good, or well in Greek, and “pheme” is speech.

Likewise, “Euphues” would be good natured or, more likely, well endowed by nature, from “phusis”, nature.