Where the Expression “To Stand on Ceremony” Comes From

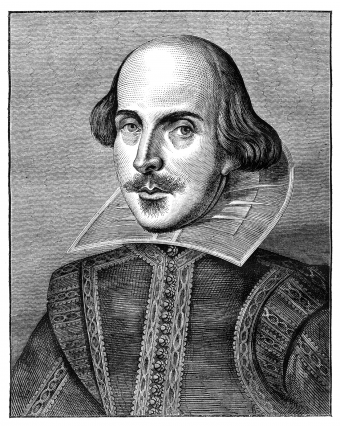

Dating back to the early days of the English Renaissance, and quite possibly having been coined by none other than the Bard, himself, the phrase “to stand on ceremony” has long been used to describe (or more often deride) a scrupulous and unproductive adherence to rules and protocol.

Dating back to the early days of the English Renaissance, and quite possibly having been coined by none other than the Bard, himself, the phrase “to stand on ceremony” has long been used to describe (or more often deride) a scrupulous and unproductive adherence to rules and protocol.

The verb “to stand” pre-dates the Norman invasion and was well used by the Middle English period. Early on, the word related to standing on the feet or remaining upright, although the connotation of being insistent upon something, and the use of the preposition “on” with the verb, can be found as early as the 15th century.

By the end of the 16th century, this latter meaning can be seen in numerous works, including notably, William Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part 2 (1591) (Act III, Scene II) where the Duke of Suffolk, in discussing the impending doom of the Duke of Gloucester with Queen Margaret, says:

And do not stand on quillets [quibbles] how to slay him:

Be it by gins, by snares, by subtlety,

Sleeping or waking, ’tis no matter how,

So he be dead . . . .

Shakespeare’s contemporary, Christopher Marlowe, likewise used this meaning in Edward II (1594) (Act IV, Scene VI). When the Earl of Leicester arrests King Edward, he says:

I arrest you of high treason here.

Stand not on titles, but obey the arrest.

Shortly thereafter, it would seem Shakespeare was the first to append (in writing that has survived to this day, at least) the noun “ceremony” in Julius Caesar (1599)(Act II, Scene II) when he has Caesar’s wife, Calpurnia, implore him with:

Caesar, I never stood on ceremonies,

Yet now they fright me . . . .

After that, the phrase became quite common, as can be seen in less elevated works, such as those by the 19th century, sensationalist author, Wilkie Collins, who in The Little Novels wrote: “Pray don’t stand on ceremony, Mrs. Callender. Nothing that you can ask me need be prefaced by an apology.”

Other writers in the 1800s, such as the historian, William Milligan Sloane, in his The Life of Napolean Bonaparte, also used the expression: “His ‘little Corsican officer, who will not stand on ceremony,’ as he called him, was to be nominally lieutenant.”

Today, the phrase has become ubiquitous in the negative as a shorthand method for discarding unnecessary procedures and getting right to the heart of the matter. As Bane said to Batman before he “unceremoniously” kicked his keister in 2012’s The Dark Knight Rises: “Let’s not stand on ceremony, here, Mr. Wayne.”

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Origin of the Phrase “As Dead as a Doornail”

- The Interesting Origin of the Word “Handicap”

- Et Tu Brute? Not Caesar’s Last Words

- How the Tradition of Saying “Pardon My French” After Saying Swear Words Started

- The Iconic “Live Long and Prosper” Hand Gesture Was Originally a Jewish Sign

Bonus Fact:

- The three brothers John Wilkes, Junius Brutus (Jr.), and Edwin Booth, all critically acclaimed actors of their day, only once appeared in the same play together. That was in a portrayal of Julius Caesar in 1864, with John Wilkes playing Marc Antony; Junius taking the roll of Cassius; and Edwin playing Brutus. The funds from the performance were donated to erect a statue of William Shakespeare in Central Park, just south of the Promenade. The statue still stands there to this day. Edwin Booth was a staunch Unionist and Lincoln supporter (who, interestingly, also once saved the life of Abraham Lincoln’s son), while John Wilkes Booth was an even more fanatical secessionist. When Edwin informed his brother he had voted for Lincoln, Wilkes Booth supposedly became rabid and asserted his belief that Lincoln would soon set himself up as king of America.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|