This Day in History: December 29th- The Murder of the Archibishop of Canterbury

This Day In History: December 29, 1170

“Will no one rid me of this troublesome priest?” –Henry II

“Will no one rid me of this troublesome priest?” –Henry II

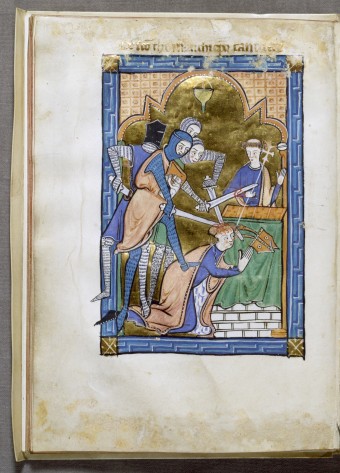

On the cold winter’s night of December 29, 1170, one of the most notorious murders of the Middle Ages occurred. To please their King, four knights crept into Canterbury Cathedral to assassinate the Archbishop Thomas Becket. This brutal event provoked a wave of revulsion and outrage throughout Europe. Cults quickly grew around the slain Archbishop as reports of miracles attributed to him abounded. Becket was recognized as a martyr by the Catholic Church and canonized in 1173.

In the 12th century, the Catholic Church was the most powerful entity in Europe. Even royalty played second banana to the Church and its leaders. In England, the highest religious authority was the Archbishop of Canterbury, who was often a political as well as a spiritual advisor to the King.

Thomas Becket, despite a relative lack of education, rose to the position of clerk for the Archbishop of Canterbury Theobald, and earned the title of Archdeacon in 1154 at the age of 36. He quickly made a favorable impression on the new king Henry II, who named him his Lord Chancellor.

The two men formed a fast friendship and became inseparable. Becket’s calm demeanor proved to be the perfect foil for Henry’s volatile temper. Thomas was also a skilled diplomat and generally well-respected, which came in handy for matters of state.

When Theobald died in 1161, Henry elevated Becket to the position of Archbishop of Canterbury, a move that surprised no-one. The King knew this would be a very pleasing arrangement, as he assumed having his best bud at the helm ensured his royal wishes would be followed to the letter.

Although hesitant at first to take the post, when he did acquiesce, Becket took his new gig very seriously. He hit the books and studied theology with renewed zeal. All of this new book learning made his loyalties turn from court to church, and drove a wedge between himself and the King.

Matters came to a head when Henry wanted to deny clerics the right of being tried in ecclesiastical courts when charged with a crime. This matter took on a certain urgency in 1163 when a canon accused of murder was acquitted by church authorities. This sparked such public outrage that the cleric was brought before the King’s court to answer the charges.

Becket cried foul and the proceedings were aborted, but Henry II went forward and amended the law anyway. The clergy would no longer be exempt from civil prosecution. Thomas wavered on the issue, but in the end refused to accept anything that would result in diminished protection for the clergy. This bit of cheek prompted the King to demand the Archbishop show himself at court in Northampton. Unwilling to face what he believed were false charges of meddling with the royal purse, Becket decided it was a good time for a little trip to France.

Once he was across the Channel, Thomas kept up his feud with Henry. He excommunicated the Bishops of London and Salisbury for undermining his authority as head of the church, infuriating the King. After years of acrimony, the two old friends met up in Normandy in 1170, and seemed to put aside their differences, even though Henry had allowed the Archbishop of York to crown his son the heir apparent in May, which cut Becket deeply.

When Becket returned to England, he not only refused to absolve the disgraced Bishops of London and Salisbury, he also excommunicated the Archbishop of York while he was at it. This pushed King Henry, still in Normandy, over the edge. The King went on an epic rant that sealed the Archbishop’s fate: “What sluggards, what cowards have I brought up in my court, who care nothing for their allegiance to their lord. Who will rid me of this troublesome priest?”

There were four knights, Reginald Fitzurse, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracey and Richard Brito who were up to the task. They sailed to England to do their king’s bidding.

The four men arrived at Canterbury on the afternoon of December 29th. Becket ran to the Cathedral where a service was being held with the four knights in hot pursuit. They overtook Becket at the altar, drew their swords (which they had hidden on the church grounds the night before) and began hacking at him until they finally split his skull open in front of horrified witnesses.

The knights, who no doubt foresaw a future of glory for their service to their monarch, instead fell into disgrace. The pope excommunicated them, and ordered that the King could not attend Mass until he had atoned for his sin. He also made him pony up 200 men for the latest Crusade to the Holy Land. As mentioned, it wasn’t long before miracles were being attributed to the murdered prelate, and he was put on the fast track to sainthood. Pilgrims flocked to Canterbury, which became a shrine to Becket.

All of this greatly unnerved Henry II and he did his penance for his part in his old friend’s death without complaint. Four years after Becket’s murder, the king donned a sack-cloth and walked barefoot through the streets of Canterbury as 80 monks flogged him with branches. He then slept in the martyr’s crypt that night as a further act of atonement.

Even though there’s some question as to whether Henry meant for Becket to be killed or he was just having an angry outburst, contemporary opinion seems to be that the King earned that sack-cloth. Henry II himself certainly seemed to think he did.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Second Pope: St. Linus, Ladies’ Heads, and Massacring Early Christians

- The Many Wives of King Henry VIII

- How the King James Bible Came About

- The Curious Relationship Between Richard the Lionheart and King Philip II of France

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Missing from this otherwise decent article is a mention of one of the vilest things that the monstrous King Henry VIII did, a few centuries later. That king was extremely unhappy about the fact that St. Thomas Becket had stood up to King Henry II, showing that the Church (and its visible leader, the Pope) was greater than the State. Henry VIII wanted to force the English people to stop thinking of Becket as a hero (and a symbolic leader of any potential anti-regal faction), so he carried out an unimaginable desecration. Here is what happened, as related at another Internet site:

“[In 1220,] in the 50th jubilee year of [Becket’s] death, his remains were relocated from [a] tomb to a shrine in the recently completed Trinity Chapel. This act of translation … was attended by King Henry III of England, the papal legate, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, and large numbers of dignitaries and magnates secular and ecclesiastical. Thus a ‘major new feast day was instituted, commemorating the translation [of the relics] … .’ This feast was suppressed [by Henry VIII] in 1536 … The shrine[, which had been a place of great pilgrimage for over 300 years,] stood until it was destroyed in 1538, during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, on orders from King Henry VIII. The king also destroyed Becket’s bones and ordered that all mention of his name be obliterated.”

Only now, after the passage of almost another 400 years, is Catholicism slowly but surely regaining its dominant position in England. Although there are still more Anglicans than Catholics, the gap has been shrinking for decades, and now more English Catholics worship on Sundays than Anglicans.