This Day in History: Novemeber 20th- Occupying Alcatraz

This Day In History: November 20, 1969

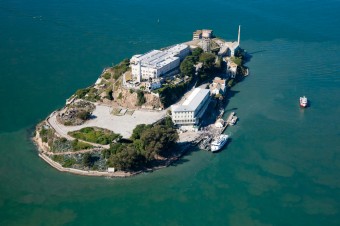

Most people remember Alcatraz Island off the California coast as the location of the country’s most notorious and isolated federal prison housing the most dangerous inmates. It closed in 1963, and the empty prison complex stood silently against the rocky, grey landscape.

Most people remember Alcatraz Island off the California coast as the location of the country’s most notorious and isolated federal prison housing the most dangerous inmates. It closed in 1963, and the empty prison complex stood silently against the rocky, grey landscape.

That is, until November 20, 1969, when a group of Native Americans, mostly students led by Richard Oakes from San Francisco State College, embarked on a chartered boat across San Francisco Bay. When they reached Alcatraz Island, they began a peaceful occupation that would continue for the next 19 months and attract massive amounts of media attention.

The group demanded control of Alcatraz so they could erect several Indian institutions, in part to replace a center that had burned down in San Francisco. They wanted to construct a center for American Indian Studies, a museum and a spiritual center on the island. But there was another motivation behind their occupation of Alcatraz, and that was the policy the U.S. had instigated 16 years earlier of closing reservations and relocating its inhabits to urban areas.

The government wanted them to vacate the island, and for three days the Coast Guard attempted to set up a blockade, but supporters managed to deliver the occupiers supplies by boat. The Native Americans approached the situation with humor and satire, declaring they claimed Alcatraz Island by right of discovery and that they were willing to pay $24 in exchange for the property. Sound familiar?

The FBI was ready to remove the group from Alcatraz, but the White House knew this would be a very bad P.R. move. They backed off, and ended any attempts at a blockade. The government even made the gesture of sitting down to talk with the Native Americans, although neither side was willing to budge an inch.

The occupation wore on, with newbies coming and veterans going. One of those living on the island for a spell was television actor Benjamin Bratt, who resided on Alcatraz with his siblings and his mother, a Peruvian Quechua native.

“Forty years later, Native people still recognize the occupation for what it was and remains: a seminal event in American history that brought the plight of American Indians to the world’s attention,” Bratt and his brother Peter said in a joint statement about the occupation.

In January 1970, things took a turn for the worse, when organizer Richard Oakes’ teenage stepdaughter died after a fall. Oakes was completely heartbroken, and left the island. Shortly after, several different factions fought for control, and eventually the Feds cut their electricity and water supply. By mid-January 1971, the last 15 people still remaining on Alcatraz Island were escorted away by federal marshals, GSA Special Forces, Coast Guard and FBI agents. They did not put up a fight.

The occupiers didn’t accomplish what they had set out to do, but in June of 1970 Nixon abolished the U.S. tribal termination policy, which was most likely a result of the attention the occupation had shed on Native American affairs. No small victory, that.

The Bratt brothers describe what they believe is the Occupation of Alcatraz’s legacy:

It’s easy to pass off the Alcatraz event as largely symbolic, but the truth is the spirit and dream of Alcatraz never died, it simply found its way to other fights. Native sovereignty, repatriation, environmental justice, the struggle for basic human rights – these are the issues Native people were fighting for then, and are the same things we are fighting for today.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- How “The Birdman of Alcatraz” Got His Name

- Al Capone Had A Brother Who Was A Prohibition Enforcement Officer

- Why Native Americans Didn’t Wipe Out Europeans With Diseases

- The Amazing Jim Thorpe

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Following the occupation of Alcatraz, the federal government became concerned that other abandoned federal properties — of which there were many — would become the target of similar “occupations.” At that time, the West Coast was dotted with abandoned Nike missile sites and similar military reservations. Small teams of Army personnel were dispatched to “un-abandon” these sites. These teams would typically spend a week or two at a site, then be relieved by a different team. I do not know know long that went on. I only know that there wasn’t a damned thing to do at these sites once the missile bunker had been explored.