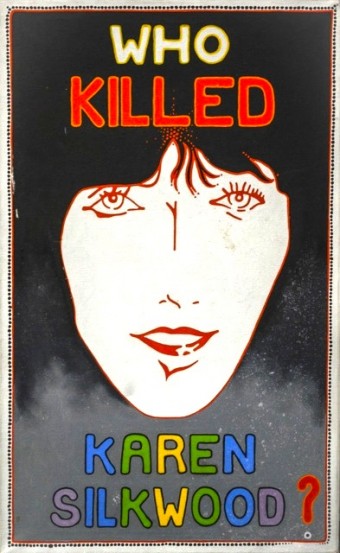

This Day in History: November 13th- The Mysterious Death of Karen Silkwood

This Day In History: November 13, 1974

On November 13, 1974, a 28 year-old technician at a plutonium plant named Karen Silkwood died in a one-car crash near Crescent, Oklahoma. She was headed to a meeting with a union representative and a reporter for the New York Times. Witnesses who saw here last claim she carried with her a folder full of documents proving that Kerr-McGee, the corporation that owned the facility where she worked, was guilty of gross negligence. When her body was found, the binder containing those documents had vanished.

On November 13, 1974, a 28 year-old technician at a plutonium plant named Karen Silkwood died in a one-car crash near Crescent, Oklahoma. She was headed to a meeting with a union representative and a reporter for the New York Times. Witnesses who saw here last claim she carried with her a folder full of documents proving that Kerr-McGee, the corporation that owned the facility where she worked, was guilty of gross negligence. When her body was found, the binder containing those documents had vanished.

Karen Silkwood was hired by Kerr-McGee in 1972. She joined the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union and became the first woman to be elected to the union’s bargaining committee at the plant. Her job was to investigate health and safety issues, and she uncovered numerous violations, including improper storage of nuclear materials, inadequate respiratory equipment, and employee exposure to contamination.

The Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union stated:“the Kerr-McGee plant had manufactured faulty fuel rods, falsified product inspection records, and risked employee safety,” and threatened to file a lawsuit against the company. Karen Silkwood testified before the Atomic Energy Commission during the summer of 1974 that safety standards at the plant had become lax because of a production speed-up.

Then, on November 5, 1974, Karen discovered her body contained 400 times the safe level of plutonium during a routine self-test at the plant, despite that she hadn’t recently been exposed to any plutonium. She was decontaminated and sent home with equipment to collect urine and feces samples for further analysis, both of which indicated high levels remained.

Over the next few days, additional testing showed a puzzling pattern – Silkwood’s continued high levels of plutonium were not being caused by a known outside source, as she had not been exposed to any new plutonium at work. Her apartment was surveyed, and high levels of radiation were present, although no-one could figure out how traces of plutonium had gotten all over her apartment.

Silkwood believed it might have happened when she accidentally spilled some of her plutonium-rich urine sample on November 7. The company claimed that Karen contaminated herself deliberately to make Kerr McGee look bad, which would seem like a rather drastic move considering the risks. In any case, Karen had no way to access the type of plutonium she had been exposed to.

But Karen Silkwood knew she had been contaminated, and that the Kerr McGee Corporation was liable. She had all her ducks in a row and had decided to go public. A New York Times reporter was interested in hearing her story, and she was on her way to meet with him when her white Honda crashed into a concrete culvert. She died before help could arrive.

At first glance, the accident appeared to be another case of asleep-at-the-wheel, especially when the autopsy revealed that Karen had a hefty amount of Quaaludes in her system at the time of her death. But an accident investigator found skid marks indicating Karen had tried to stop her vehicle, and a dent and paint chips from another vehicle in the rear bumper suggesting someone may have forced her off the road. Witnesses who saw her drive away from the union meeting she had been at said there was no damage to the rear of her car before she left and she had a binder with incriminating documents with her at that time. When police found her body and car, the binder was gone.

Karen Silkwood’s father Bill and her three children sued Kerr-McKee for negligence. The trial took place in 1979 and lasted ten months, which made it the longest trial in Oklahoma history up to that point. Silkwood’s estate maintained that Karen’s autopsy was definitive proof that she had been poisoned by plutonium at the time of her death. A series of former Kerr McGee employees served as witnesses.

The defense purported that Silkwood was a troublemaker who had poisoned herself, but, after some legal wrangling, the two sides eventually settled out of court for $1.38 million in 1986.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Tragic Family Life of Kelsey Grammer

- The United States Once Planned On Nuking the Moon

- Why Can People Live in Hiroshima and Nagasaki Now, But Not Chernobyl?

- The Tunguska Event, a 1908 Explosion Estimated at 1000 Times More Powerful Than the Atomic Bomb Dropped on Hiroshima

| Share the Knowledge! |

|