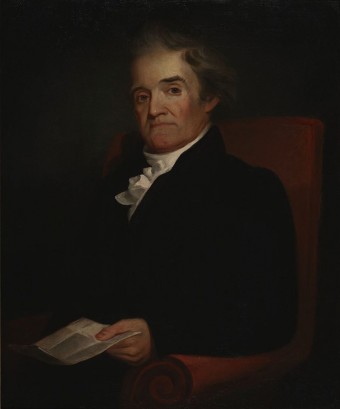

Noah Webster and Moving Away from British English

Eliminating the unnecessary u, many duplicate consonants, the redundant e, converting diphthongs into simple vowels and turning the combination of e and r at the end of a word the right way around, Americans significantly changed the spelling of many English words. And it was done with the best of intentions – to make spelling easier.

American English began to deviate from British English as soon as the United States won its independence from Great Britain. The brainchild of Noah Webster, the differences in spelling between the two dialects are essentially based upon Benjamin Franklin’s idea that “people spell best who do not know how to spell,” meaning the more phonetic and logical, the better the spelling.

In 1783, Webster first published his suggestion for changing certain spellings in the Grammatical Institute of the English Language with its appendix An Essay on the Necessity, Advantages and Practicability of Reforming the Mode of Spelling, and of Rendering the Orthography of Words Correspondent to the Pronunciation.

He transformed this scholarly treatise into a practical work later that same year with the first edition of his American Spelling Book. An overnight sensation, Webster’s guide to spelling soon replaced its predecessor (Dilworth’s Aby-sel-pha) and remained popular for the next 100 years (although in 1829, the name changed to Webster’s Elementary Spelling Book).

Moving out of the classroom, Webster published his first dictionary in 1806, and his first American Dictionary of the English Language in 1828, both with many spellings simplified, including a number of changes we see in modern American English today such as eliminating the silent u (color for colour), unnecessary double consonants (jeweler for jeweller) and switched around the re (theater for theatre).

His radical ideas didn’t stop there, and many changes found in those early dictionaries did not stick. These included removing the final, silent e (as in determin for determine), the silent b (thum for thumb), the s in island and the o in leopard. He also changed ph to f (fantom for phantom), porpoise to porpess and tung for tongue. Many of these unusual spellings he held onto through his life, however, and they did not disappear from his dictionaries until well after his death.

Although some of these new spellings were his own, many had long been in use, but their adoption into the mainstream was contested by many, including notable Americans Washington Irving and William Cullen Bryant.

Webster’s mission was picked up again in the 1870s when the American Philological Association (APA) and the International Convention for the Amendment of English Orthography both decided changes were necessary. Many, both in England and the United States, worked on the project, including Lord Tennyson, Charles Darwin, Sir J.A.H. Murray and Sir John Lubbock, and in 1883 they issued several recommendations. Shortly after, in 1886, the APA issued its own list, this one, essentially all Webster’s ideas, changing the spellings of 3,500 words (but organized under 10 headings).

Many of these ideas were adopted, and by 1921, H.L. Mencken noted 18 distinct differences between English and American orthographies. Of course, Webster’s elimination of the unnecessary u was adopted (armor for armour), as was the elimination of the unnecessary double consonant (counselor for counsellor) ,many redundant e’s (asphalt for asphalte) and the switch of re to er (center for centre).

Other differences included the elimination of certain foreign endings (catalog for catalogue), and the u when it was with an a or o (balk for baulk and mustache for moustache). Diphthongs (two vowels stuck together like æ) were replaced with simple vowels (anemia for anæmia), as were compound consonants with simple consonants (plow for plough).

For some reason, o was sometimes replaced with an a or u (naught for nought and slug for slog), e was sometimes changed to i (inquire for enquire), y into either an a, ia or i (baritone for barytone and pajamas for pyjamas.) and k for c (skeptic for sceptic). In addition, many c’s and z’s were switched for s’s such as defense for defence and advertisement for advertizement.

Other words were made more complex, including adding an e to words like forego (for forgo), a ct for x (connection for connexion) and y for i (as in dryly for drily). Finally, there are some words that follow no particular pattern, but are simply spelled different like gasoline for gasolene and czar for tzar.

Altogether, although many of the spelling changes adopted by Americans made spelling easier, others don’t seem to add anything in terms of simplicity, phonetics or logic. This last has led many to question the need for standardized spelling, including President Andrew Jackson who famously said, “It is a damn poor mind that can think of only one way to spell a word.”

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Why Do the British Pronounce “Z” as “Zed”?

- Why British Singers Lose Their Accents When Singing

- Why Some Countries Drive on the Right and Some Countries Drive on the Left

- The British Equivalent of “That’s What She Said”

- The Differences Between British and American English

Bonus Facts:

- The reason the Boston Red Sox and the Chicago White Sox spell their name with an x also is from the attempt to simplify English spelling. From this, it was common at the time to see socks spelled s-o-x.

- In March 2014, the Oxford English Dictionary released its new word list that included notable entries such as bestie, chugging, coney, cunted (as well as cunting, cuntish and cunty), death spiral, demo, empath, exfoliator, hegemonize, honey trap, impervium, scientific socialism, scientificality (and scientificness), shvitz, TP (as a noun and a verb), tropicalismo, wackadoo and wackadoodle. Not to be outdone, in August 2014, Merriam-Webster released a fifth edition of The Official Scrabble Players Dictionary that included more than 5,000 new words such as hashtag, chillax, mojito, mixtape, beatbox, Sudoku, yuzu and geocache.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

“turning the combination of e and r at the end of a word the right way around”

How pompous is this? The word was created the way it was, therefore the “right way round” in the first place.

If you could like comments on this site, I’d like yours.

Same, I’m Welsh but I’m living in Florida, its absolutely rubbish.

“And it was done with the best of intentions – to make spelling easier.”

So basically, you’re confirming the thing that all you Yanks seem to get so wound up about by the rest of us saying; that you changed the spelling because you’re lazy.

“The reason the Boston Red Sox and the Chicago White Sox spell their name with an s also is from the attempt to simplify English spelling. From this, it was common at the time to see socks spelled s-o-x.”

I think you meant spelled with an “x” instead of “s”.

@John: Indeed! Thanks for catching that. Fixed.

There is so much more to English spelling than your story presents.

Writing English encodes spoken English. Silent letters signify to readers how to pronounce preceding vowels, (e.g., bake, time, cute). How would know tim from time? How would you know cut from cute? How would you know bak from bake? In words that end u or v (e.g., love, true), how would you know to say luh-of rather than loff or tr-ew rather than tr-uh?

What about words ending in c or g, (e.g., chance, allege). How would you know to not say ‘chank’ instead of chance or alleg instead of ‘alledge’?

Do you know of any words in English where syllables lack vowels, except words of onomatopoeia and interjection? What happens to words like little, castle, bottle, fiddle?

Without a silent e, how would you know dense from dens? How would you know fore from for or ore from or?

Spelling signals words of foreigners. Many foreign words retain spelling.

Words of Old French and Middle French origin were spoken first by English speakers who could speak those words and pronounced as natives would have pronounced those words in what is contemporary northern France. Today’s English speakers do the same with words like coup d’etat, eclair, à la carte, à propos, art nouveau, au gratin, au jus, ballet, bon voyage, café, carte blanche, crème brûlée, garçon and many more.

And then you have the problem of whose pronunciation of English is right? Do Bostonians pronounce English right and the rest of us have it wrong? Or do those who speak Appalachian English have it right? Or is it those who speak Pittsburgh English? Or is it those who speak Great Lakes English? Or is it those who speak Southern English? Or is it those who speak Californian English?

Should there be different spellings of words to accommodate all speakers with their peculiar regional pronunciation?

Bad spellers arise from lame teachers who don’t understand English and thus cannot teach English, even when licensed to do so. Ironically, most native speakers of English don’t even understand their own language.

Couldn’t agree more with Ken U. Beleevit. This is why changing spelling is a fool’s errand, especially in this day and age when spell checkers and autocorrect features exist. Rather than trying to change spelling to be different from the rest of the world in an attempt motivated by blind nationalism, the US should just adopt Oxford spelling, the most etymologically correct and international spelling of the English language.

Fighting with the rest of the world serves no one and is a waste of time, energy, and money. This effort would be better spent teaching everyone the Shavian/Shaw alphabet for English, which would result in a significant improvement in people’s spelling and literacy.