That Time About Two-Thirds of China’s Population, and then a Decade Later About Half of Europe’s, Up and Died

Pandemics have been the bane of humanity throughout history. Although the past few centuries have witnessed numerous epidemics, and even a handful of pandemics, none compare to the Black Death of the 14th century in terms of percentage of the Earth’s human population killed in a very brief period of time.

The Bubonic Plague

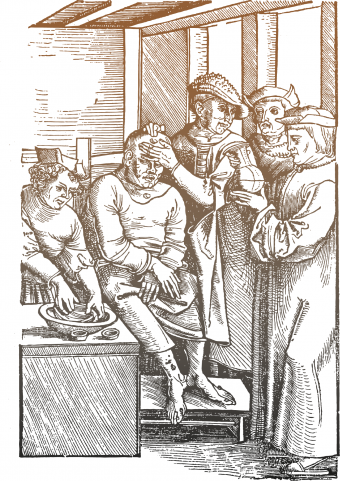

Caused by the bacteria, Yersinia Pestis, and carried by rodents, the plague infects people through fleabites. Prior to the dawn of antibiotics, the few times in history the bubonic plague popped up, it had devastating effects. Highly lethal if untreated, symptoms include fever, severe pain and black, pus-filled boils covering the skin (hence the name).

Although some scholars believe the bubonic plague may have contributed to the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 2nd century AD, the first recorded instance arose in the Byzantine empire in the 6th century AD. Named after the emperor, the Justinian Plague that lasted for the next 200 years eventually killed over 100 million people across the Mediterranean.

About 500 years later, the bubonic plague appeared again, this time in China. In 1334 in the northeastern province of Hopei, a new epidemic struck. By the time it was over, nearly 2/3 of China’s population, around 5,000,000 people, had died.

The Black Death (1347-1353)

By the 14th century, international trade spanned the eastern hemisphere. From China (then ruled by the Mongols) in the east to England in the west, trading caravans journeyed the Silk Road and other routes, while the great ships of city states like Venice and Genoa sailed the oceans, spreading commerce and contagious disease.

The Genoese Black Sea port city of Kaffa, on the Crimean peninsula (today, a territory disputed by Russia and Ukraine), was the first site of the Black Death that would eventually ravage Europe.

For nearly a year before the plague came, Kaffa had been under siege by the Tartars, the powerful Golden Horde whose territory spanned from Mongol territory in the east to the Danube in the west. In 1347 when the plague arrived the Tartars ended their siege, but not before they catapulted plague-infected corpses over the walls and into the city. Although experts dispute the precise origin of the contagion, many believe it was from the same plague that had devastated China a decade before, and had just taken 10 years to make its way across the Horde’s vast territory.

Regardless, after the siege the Genoese in Kaffa established a pattern that would repeat itself throughout the pandemic: ships carrying the plague from one infected city would visit a new city, bringing the plague and spreading the pandemic.

So, early in 1347 a handful of ships left Kaffa with those on board believing (or at least praying) that they were free from plague. Sadly no, and soon after they docked in Constantinople in May 1347, the plague was spreading throughout that center of international commerce and trade.

Thereafter, as ships left Constantinople they carried plague. By September, the plague had spread to Marseilles, and by October and November, to several ports in Italy including Messina, Genoa, Venice and Pisa (the seaport for Florence).

From its early arrival in Marseilles in September 1347, the plague quickly spread up the Rhone to Lyons and southwest toward Spain, and both were under the thrall of epidemic by March of 1348.

Bordeaux was also pestilential by the spring of 1348, and from that commercial hub, the plague spread to a number of sites, including La Coruña and Navarre (Spain), Rouen and Paris (France), and then Belgium and the Netherlands.

Ships from Bordeaux also carried the plague to Melcombe Regis in England in May of 1348. It had reached Bristol and Pale, Ireland by June and London by August of that year.

The plague also tore through Italy: nearly 3/4 of Venetians and 7/10 of Pisans died during the Black Death. From April through October of 1348, 80,000 people died in Sienna, and although contemporary accounts vary, between 60,000 and 100,000 died in Florence. In sum, it is estimated that half of the population of Italy perished during the Black Death.

By the fall of 1348, the plague had reached Oslo, Norway from which it eventually spread to Denmark and Sweden in July of 1349. The Prussian town of Elbing on the Baltic Sea suffered from an outbreak in August 1349, from which the plague then spread south into Germany (which was already besieged by plague moving northward from Austria and Sweden).

The Black Death eventually made its way to the Russian city of Novgorod in the fall of 1351, with the larger outbreak occurring in spring 1352. Moscow succumbed to plague in 1353.

Although experts disagree, it is estimated that the Black Death killed around 60% of the European population, reducing the Earth’s total human populace from about 430 million people to about 350-375 million. The estimated annual death rate from the plague in Europe was over 8,000,000 each year. This was by far the worst of any known pandemic in history, only rivaled by the Spanish Flu of the early twentieth century which killed off approximately the same total number of people, but worldwide, even reaching into the Arctic. For reference, when the Spanish Flu hit, the human population was also much higher at around 2 billion people.

The Silver Lining

With so few people remaining after the pandemic burned itself out, European laborers saw an increase in bargaining power. Serfdom (a form of bondage similar to share cropping) ended in many places and wages, and the standard of living of peasants, increased.

These changes led to other transformations in European society and its economy, and when urban populations swelled again in the 15th century, the middle class of bankers, merchants and tradesmen grew.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Why Native Americans Didn’t Wipe Out Europeans With Diseases

- The Mysterious Encephalitis Lethargica Epidemic of the Early 20th Century

- It is Possible for a Person’s Muscles and Other Connective Soft Tissues to Turn to Bone

- 1374: Thousands of People on the Streets of Aachen, Germany Suddenly Suffer from the “Forgotten Plague”, Dance Mania

- The True Story Behind The Appalling Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

Bonus Facts:

- Forgotten but not gone, the plague continued to pop up here and there over the centuries that followed the Black Death, including killing 10 million people in India alone in the 19th century. Today, it remains alive and well (so to speak). In July of 2014 in Yumen, Gansu Province, China, 151 people were quarantined and the entire city was closed after a 38-year-old man died from bubonic plague. It is believed he caught it from a flea that was on a dead marmot he had been handling. Luckily, the CDC says modern antibiotics will still effectively treat bubonic plague.

- While the Black Death killed off a significant portion of the human population, there were still plenty of humans to go around. This was not the case about 200,000 years ago when the human populace dropped so low that we can all trace a common female ancestor, known as Mitochondrial Eve. As you’ll see if you follow the link to the full article, this was not the only time this happened and we all also have a common male ancestor known as Y-Chromosome Adam who lived during a separate period in history than Mitochondrial Eve (about 90,000 years ago). For more on this, see: The Woman Who is the “Mother” to Us All

- The Afro-Eurasian Trading System in the 13th and 14th Centuries

- Black Death – Facts & Summary

- The Black Death: The Greatest Catastrophe Ever

- Black Death Migration (Wikipedia)

- CDC-History-Plague

- Chinese city sealed off after bubonic plague death

- The Death Toll

- Definition of a Pandemic

- Five Deadliest Outbreaks and Pandemics in History

- Golden Horde (Wikipedia)

- How the Plague Spread to Italy

- The Lasting Consequences of Plague in Siena

- Renaissance – Out of the Middle Ages

- Social and Economic Effects of the Plague

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

There was no “Belgium” in the 14th century. You must have meant Flanders.

“It had reached Bristol and Pale, Ireland by June and London by August …”

Pale isn’t a city or geographic region in Ireland! “The Pale” (the term includes the definite article in every reference I’ve ever seen) was the term for the part of Ireland under English control (generally Dublin and surrounding counties). Parts of Ireland that weren’t “English” were referred to as “beyond the Pale.” So although the Pale was a political region, it was never a static geographic region, and writing “Pale, Ireland” looks very,very strange (and wrong!).