The Legend of Spring Heeled Jack

During the early years of the Victorian era, an imposing figure dressed in black terrorized the English countryside almost unchallenged. According to eyewitness accounts, this specter had bulging, red eyes, pointy ears and razor-sharp metal claws. He would materialize to attack unsuspecting victims, and when townsfolk gave chase, easily outmaneuvered them by effortlessly jumping over high fences and hedgerows to evade capture. The name of this man/beast/demon was Spring Heeled Jack, and his legend is still alive and well today.

Jack’s first known appearance was in 1837. A local businessman was making his way home from work, when a cloaked figure with inhuman features leapt over the imposing gates of the local graveyard in one fluid motion. The businessman wasn’t harmed, but he hurried to the safety of his home as fast as his trembling legs could carry him.

Later that same year, a young lady named Mary Stevens was heading to her home in South West London when the creature suddenly attacked her, emerging from a dark alley and subduing the horrified girl by gripping her arms. He began to kiss her face and attempted to cut her clothes off with his talon-like fingernails, his hands “cold and clammy as those of a corpse.” The victim began to scream hysterically, and the figure in black retreated back into the darkness. A group of people who had responded to Mary’s cries for help gathered at the spot, but an attempt to hunt down the attacker ended in vain.

The very next night, a figure jumped into the path of a carriage, causing the driver serious injury. Witnesses claim that the perpetrator escaped from the scene by hopping over a 9-foot fence, cackling maniacally as he disappeared into the coal-black night. It wasn’t long before the local press got wind of these stories, and dubbed the elusive assailant as Spring Heeled Jack.

In January of 1838, Jack’s fame grew wider as the Lord Mayor of London made public an anonymous letter which read in part:

It appears that some individuals (of, as the writer believes, the highest ranks of life) have laid a wager with a mischievous and foolhardy companion, that he durst not take upon himself the task of visiting many of the villages near London in three different disguises — a ghost, a bear, and a devil; and moreover, that he will not enter a gentleman’s gardens for the purpose of alarming the inmates of the house. The wager has, however, been accepted, and the unmanly villain has succeeded in depriving seven ladies of their senses, two of whom are not likely to recover, but to become burdens to their families.

At one house the man rang the bell, and on the servant coming to open door, this worse than brute stood in no less dreadful figure than a spectre clad most perfectly. The consequence was that the poor girl immediately swooned, and has never from that moment been in her senses.

The affair has now been going on for some time, and, strange to say, the papers are still silent on the subject. The writer has reason to believe that they have the whole history at their finger-ends but, through interested motives, are induced to remain silent.

The mayor was understandably skeptical about the contents of the letter, but a member of the audience chimed in that several young women in Hammersmith, Ealing and Kensington also told tales of encounters with this demonic figure. In short order The Times picked up the story, and more victims came forward claiming terrifying sightings of the imposing apparition, which had allegedly caused some of those unlucky enough to cross his path to literally die from fright. As reports of Jack’s menacing attacks spread, the mayor knew he had an explosive situation on his hands. He ordered the police force to make the apprehension of this ghoul a top priority, and offered a tempting sum as reward for his capture.

In spite of the ever-increasing efforts to apprehend him, Spring Heeled Jack was approaching the zenith of his illustrious career. A month after the mayor’s proclimations, two attacks occurred within days of each other that sealed Jack’s infamy for all time. On a cold February night in 1838, a girl named Jane Allsop answered a knock at the door. When she opened it, a cloaked police officer told her to grab a light, as they had captured Spring Heeled Jack. The girl quickly handed the man a candle, only to have him roughly slap it from her hand and show his true identity.

As the story went, the “officer’s” red eyes mirrored the flames of Hell as he spewed white-hot flames from his mouth. Adding to the macabre nature of the scene, the creature was clad in a skin-tight black suit of oil-skin and a matching black helmet. He attacked the terrified girl with his metallic fingernails, cutting her clothes to ribbons, and ripping the skin of her neck and arms. Jane’s screams alerted her sister, and Jack disappeared into the mists just as she appeared to confront her sister’s attacker.

Just over a week after this incident a young woman named Lucy Scales was walking home with her sister when the ghoul appeared in their path, breathing flames that blinded her, and initiated a hysterical fit that went on for several hours. Her brother, alerted by the sound of his sister’s screams, showed up to find Lucy writhing on the ground as their sister attempted to comfort her. A search was conducted, and several arrests were even made, but in the end the culprit once again eluded capture.

Following the attack on poor Jane Allsop, a man named Thomas Milbank was bragging that he was Spring Heeled Jack. The clothes Milbank had been wearing at the time of the attack had been found, along with (apparently) Jane’s candle which was in Milbank’s pocket. But, alas, Milbank lacked the ability to breathe fire, which Jane insisted the culprit could do. Milbank was ultimately cleared of all charges.

Of course, James Smith, who claims to have witnessed the tail end of the attack and later heard an intoxicated Milbank and a companion of his, Payne, discussing the event, said that no fire was present except for that introduced by the candle. He also claimed there was no real violence in the “attack,” seemingly simply a practical joke. As for Milbank, he claimed he had been too drunk to remember much of what went on that night.

Others have pinned at least the first instances of Spring Heeled Jack jumping out at people on Irish nobleman the Marquess of Waterford, a.k.a. “the Mad Marquis,” known for his contempt of women, willingness to do just about anything if someone would bet that he wouldn’t, and thinking it funny to jump out at random travelers to scare them. Beyond that, it’s generally thought later instances were likely just copycats, with the supernatural attributes simply growing in the telling, or the product of an overzealous imagination as would appear to be the case with the Jane Allsop attack.

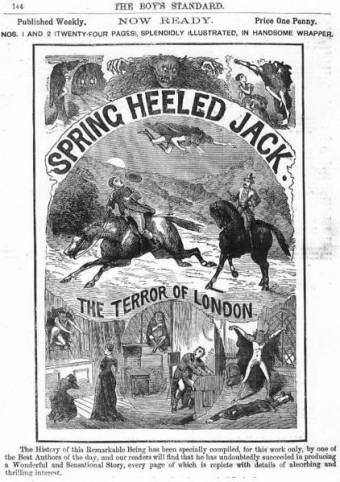

The legend of Spring Heeled Jack was kept alive through the 1870s by the penny dreadfuls and tabloid journalism of the time, with noteworthy reports of mayhem caused by him coming from Aldershot, a town in England known for its Army barracks. But in the late 1880s, Spring Heeled Jack was eclipsed by another Jack even more monstrous than himself, who hunted Victorian women by gaslight and gutted them randomly and mercilessly – Jack the Ripper.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Why are Carved Pumpkins Called “Jack O’ Lanterns”?

- The Greatest Practical Joke of the 19th Century

- The Fascinating Origin of the Word “Abracadabra”

- The Origin of Friday the 13th as an Unlucky Day

- Why a Rabbit’s Foot is Considered Lucky

| Share the Knowledge! |

|