The Goingsnake Shootout

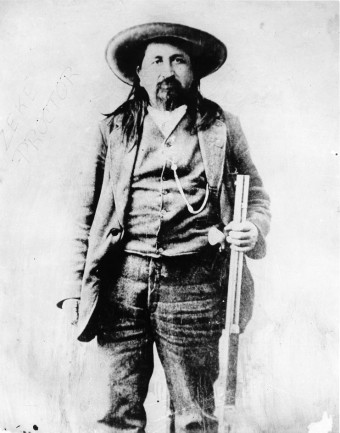

Ezekiel Proctor was a 19th century Cherokee man who had walked the Trail of Tears from Georgia to the Indian Territory when he was just seven years old. He was proud of his heritage, and he still spoke the language and basked in the customs of the Cherokee people. When he grew up, he became a lawman.

Ezekiel Proctor was a 19th century Cherokee man who had walked the Trail of Tears from Georgia to the Indian Territory when he was just seven years old. He was proud of his heritage, and he still spoke the language and basked in the customs of the Cherokee people. When he grew up, he became a lawman.

Jim Keterson was a white man who married Proctor’s sister. The pair had several children together, but Proctor didn’t like Keterson—especially not when Keterson left his sister and their children for another woman. That woman was Polly Beck, another member of the Cherokee tribe.

When Proctor went to confront Keterson about abandoning his wife, he took a gun. But when he pulled the trigger, Polly Beck got in the way of the bullet. She died almost instantly.

Needless to say, Proctor hadn’t been intending to kill Polly. Afterwards, her direct family wanted Proctor dead; the Cherokee tribe wanted to try Proctor as he had killed one of his own tribeswomen; and the U.S. Government wanted Proctor to pay with his life primarily because his intended victim had been white.

Unfortunately, there were a lot of territorial issues that confused the trial and prosecution. The U.S. government had no jurisdiction over the Cherokee lands, even though Proctor’s intended victim had been a U.S. citizen. Polly Beck’s family didn’t want Proctor tried by the Cherokee court, because they felt he would get off easy since many people in the tribe were related to him.

Even so, Proctor’s Cherokee court trial was scheduled for April 15, 1872, in the Goingsnake District of what would later become Oklahoma.

Angered by the decision, Polly’s family decided to petition for Proctor to be tried at a U.S. court in Arkansas. The United States government agreed, and they sent U.S. marshals to collect Proctor and take him to be tried—and likely killed—for his crime. The U.S. marshals were no strangers to violence on the Cherokee lands, however, and decided to take a group of 13 armed men to transfer Proctor to Arkansas, just in case they ran into any trouble. This group included members of the Beck family who were still sore over the death of Polly.

The Cherokee nation was determined not to allow the U.S. government to interfere. Many people came to the trial armed and prepared to fight for the right to prosecute Proctor. Even the judge and Proctor himself had guns.

Needless to say, when these two groups met at the schoolhouse where the trial was to take place, it didn’t go well. No one knows who fired the first shot, but after it rang out everyone started shooting indiscriminately.

What would become known as the Goingsnake Shootout lasted only a few minutes, but it left eleven men dead and others seriously wounded. Eight of the men killed were U.S. marshals, making it the largest loss of life in a single incident for the agency.

Proctor’s attorney was also killed, and Proctor himself was wounded in the shooting, but the trial had to go on. The very next day, Proctor underwent questioning about his killing of Polly Beck. As the Beck family had feared, the jury acquitted him of the murder.

The U.S. government got another band of marshals together to collect Proctor and the others who participated in the shootout in order to prosecute them for the killing of eight marshals. But when the Cherokee chief was confronted and asked to hand the men over, he said that the tribe would take care of the punishments instead. Not wanting another incident, the U.S. government backed down and decided not to pursue the matter.

This wasn’t unusual at the time. There were about 200 U.S. marshals who patrolled the vast Indian Territory at any given point and between 1872 and 1907, 119 officers were killed in the Indian Territory. Federal Judge Parker headed the justice system for the Western District of Arkansas for 21 years starting in 1875, and during that time only 5 people were tried and hanged for the crime of killing a U.S. Marshal in the Indian Territory.

Everyone else got away with it—and some, like Proctor, were considered heroes for their crimes. Proctor even ended up becoming a deputy U.S. marshal himself, and wound up dying in his bed of pneumonia at the age of 76.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Why Native Americans Didn’t Wipe Out Europeans With Diseases

- Native Americans Were Not Introduced to Alcohol by Europeans

- The First Convicted Murderer in America

- Where the Tradition of Yelling “Geronimo” When Jumping Out of a Plane Came From

- “Billy the Kid’s” Real Name was Not William H. Bonney

Bonus Facts:

- It’s thought that part of the leniency granted to those killing U.S. marshals at this time in the South stems from the fact that U.S. marshals represented the northern government, and in the southern courts they were looked down upon; a not insignificant portion of Southern citizens thought the marshals got what they deserved. So while it was good news for the murderers, it was not such great news for the dead marshals’ families. The Indian Territory marshals did not earn very much each year, and the government did not pay for their funerals or give their families a pension. Most of the marshals’ killers were never caught.

- If the Indian Territory marshals had such a thankless, dangerous job, why did anyone choose to become one? Most of them were simply seeking adventure. They didn’t want to become farmers or whatever life at home had in store for them.

- The marshals were in the territory in the first place because the territory attracted a lot of white criminals who thought that they could escape U.S. justice by conducting their nefarious activities on Native American soil. But the marshals also helped Native Americans by stopping timber poaching and stopping whites from settling on Native American land.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

One comment