The First Person to Play for Both Baseball’s National League and American League All-Star Teams was a Woman: Lizzie “The Queen of Baseball” Murphy

On August 14, 1922, a collection of baseball stars gathered at Fenway Park in Boston. An exhibition all-star game had been set-up to honor and raise money for the family of Tommy “Little Mac” McCarthy- Boston Red Sox great in the 1880s and 1890s. The game featured the Boston Red Sox, World Series champs only three seasons ago, versus a group of professional baseball players, some who actually played in the majors and others who made their living barnstorming.

On August 14, 1922, a collection of baseball stars gathered at Fenway Park in Boston. An exhibition all-star game had been set-up to honor and raise money for the family of Tommy “Little Mac” McCarthy- Boston Red Sox great in the 1880s and 1890s. The game featured the Boston Red Sox, World Series champs only three seasons ago, versus a group of professional baseball players, some who actually played in the majors and others who made their living barnstorming.

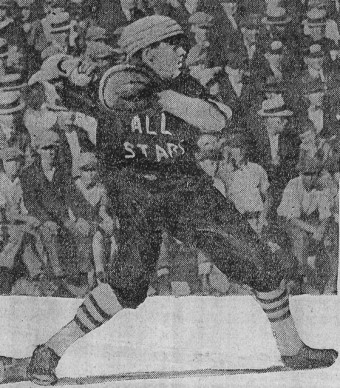

About half-way through the game, Lizzie Murphy, the proclaimed “Queen of Baseball,” subbed in to play first base. Met with jeers – and even louder cheers – her entrance into the game made history; Lizzie Murphy had become the first female to play in a baseball game against major league players. But that wasn’t and wouldn’t be the only time Lizzie “Spike” Murphy would make baseball history. She made something of a habit of it, in fact.

While baseball was her true love, Lizzie was born an athlete. She participated in everything from ice hockey to soccer to swimming to long-distance running in her hometown of Warren, Rhode Island during the early 1900s. She told a reporter once, in 1941, that she “always loved boys’ sports. They’re so active, they wake you up.” She was such a good ice skater that her brother Henry claimed that no boy or girl could even come close to keeping up with her on the ice. But baseball was what she wanted to play.

Lizzie’s father was an avid amateur baseball player himself when he had time off from his job at the mill. He encouraged Lizzie, thinking her tomboy phase was eventually going to pass anyway. As for her mother, she didn’t love the idea of her only daughter being so into sports. Despite this, everyone could see Lizzie was destined for the baseball life. Henry would play catch with her, wincing as her fastballs smacked his glove.

As was customary back then for children of working-class families, when she turned twelve, Lizzie left school and took a job, in her case working in the Parker woolen mill as a ring spinner. That still didn’t stop her from playing baseball. She played after work, on the weekends- whenever she could. In an interview with Sports Illustrated in the early 1960s, she said,

Even then, when I was too small to play, I used to beg the boys to let me carry the bats. Finally, I was allowed to join the team for only one reason: I used to ‘steal’ my father’s gloves and bats and bring them along, so I was a valuable asset to them when I could furnish some of the equipment.

She immediately left her mark with the boys and soon was the first player chosen in nearly every game. In fact, she was so good that by the age of 15, she was playing with men on local business teams like the Warren Shoe Company.

At 17, she became a professional and signed on to play for a Warren semi-pro club. Though her skills were immense, it wasn’t lost upon the team’s owner that Lizzie was an attraction and could bring in a crowd.

In those days, fans in these leagues didn’t typically pay admission to the games, but rather a hat was passed around after the nine innings and coins were thrown in. The owners would divvy up payment when this concluded. After her first game on the semi-pro club, Lizzie received no payment. The next week, the team had a game scheduled in Newport, Rhode Island. A wealthy port town with a fine amount of sailors looking forward to seeing Lizzie’s strawberry hair under her cap; the owner thought he was going to make a healthy profit that day in Newport.

As the story goes, Lizzie showed up all week long to practice and workouts, never once mentioning her “forgotten” payment. On Saturday morning, mere hours before the game, as everyone got ready, Lizzie approached the owner and told him “No money, no Newport.” Without much choice or leverage at this stage with so many coming to see Lizzie play, the owner agreed to pay her a five dollar flat rate (about $121 today) every game from then on, plus a share of the collection. Because of this, Lizzie Murphy made history, becoming the first known female holdout in professional sports.

A few years later, she was signed by the Providence Independents and, then, by Ed Carr’s All-Stars of Boston. Said Carr at the time of the signing to a group of reporters,

No ball is too hard for her to scoop out of the dirt and when it comes to batting, she packs a mean wagon tongue.

The team traveled across southern New England and, then, into Canada, pulling in crowds wherever they went. It was estimated that they played upwards of hundred games during the season, which lasted from April to August. Boasted Carr to reporters,

She swells attendance and she’s worth every cent I pay her. But more important, she produces the goods. She’s a real player and a good fellow.

Besides being a good baseball player, Lizzie also had a good head for making money and marketing herself. To supplement income, she would go into the crowd herself after games, selling picture postcards of herself in uniform for a dime. She liked to say whatever town bought the most postcards was her favorite town.

She also wore the same uniform as all the men – save for one pretty notable exception. The front of her shirt didn’t have the team’s name, but rather “Lizzie Murphy” stitched across it, as evident in a picture of her at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. She wanted to make sure everyone knew that the woman the fans had paid to see was, in fact, playing first base, and what her name was.

She also wore the same uniform as all the men – save for one pretty notable exception. The front of her shirt didn’t have the team’s name, but rather “Lizzie Murphy” stitched across it, as evident in a picture of her at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. She wanted to make sure everyone knew that the woman the fans had paid to see was, in fact, playing first base, and what her name was.

Despite Murphy getting most of the attention, she never had any issues getting along with her teammates. She once told the Providence Journal that, she “didn’t have any trouble with the boys. Of course, they cursed and swore, but I knew all the words.”

Well, there was one incident in that 1922 all-star game. After Lizzie entered the game, in that same inning, there was a sharp grounder to third. Legend has it (and according to Murphy’s recollection), the third basemen held on to the ball and waited for the runner to get closer to first. He then zipped the throw hard and wide. Murphy, like she’d done throughout her life, handled what was thrown at her with ease. She caught the ball for the out. The third baseman turned to the shortstop and said, “She’ll do.”

As Murphy said later to Sports Illustrated, “What he didn’t know was that I liked fast ones better than slow.”

Lizzie would go on to have two more firsts. In 1928, she played on a National League all-star team (in a game against the Boston Braves), becoming the first person of any gender to play for all-star teams in both the American and National leagues.

She also became the first woman to play in the Negro Leagues, when she played first base for the Cleveland Colored Giants when they came through Rhode Island. According to the Exploratorium, a museum in San Francisco, Lizzy actually got a hit off of legendary Negro League pitcher (and Baseball Hall of Famer) Satchel Paige.

Catcher Josh Gibson, one of the greatest power hitters of all time and also eventual Cooperstown-inductee, was asked if Paige really had given Murphy all he had. Gibson responded with an angry “Of course, he did!” because Paige would have never wanted to have the embarrassment of giving up a hit to a woman.

Lizzie Murphy hung up her spikes and jersey for good in 1935 at the age of forty. She spent the rest of her life in her hometown of Warren, passing away at the age of 70 in 1964.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- There Once was a 17 Year Old Girl Who Struck Out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig Back to Back

- Hall of Famer Richie Ashburn Once Struck a Spectator with Foul Balls Twice in the Same At Bat, the Second Time as She was Being Carried Off on a Stretcher

- The Woman Who Batted During a Major League Baseball Game

- The Only Major League Baseball Player to Openly Admit He was Gay During His Career Also May Have “Invented” the High-Five

- 10 Fascinating Baseball Facts [Infographic]

Bonus Facts:

- Because her mother was French-Canadian, Lizzie was fluent in French (well, Quebecian-French). While playing in Quebec with Ed Carr’s team, she overheard the first base coach telling the runner to steal second, completely unaware that Lizzie also spoke French. She called time and worked out a hand signal with her catcher. The catcher threw out five runners attempting to steal second that day.

- Lizzie Murphy may have been the first, but she wasn’t the only woman to play against major league men. In 1931, a pitched named Jacki Mitchell was signed by the Class-AA Chattanooga Lookouts and their owner Joe Engel. A few days later, she pitched against the New York Yankees – and their legends Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. She promptly struck both of these gentlemen out on six pitches combined. For her efforts, her contract was voided and she was banned from the majors by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, stating that baseball was “too strenuous” for women to play.

- Babe Didrikson, another woman to play against major leaguers, pitched in two exhibition games for the Philadelphia Athletics, but she was more known for her other athletic achievements – most notably winning two gold medals and one silver in track and field in the 1932 Olympics.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Um…”Quebecian”??

Quebecois, s’il vous plait.