The Orangeburg Massacre of 1968

Today I found out about the Orangeburg Massacre of 1968.

Today I found out about the Orangeburg Massacre of 1968.

As with many massacres around this turbulent time in history, the Orangeburg Massacre had its beginnings in race relations. In February, 1968, black students at South Carolina State College were prohibited from using the lanes at a nearby bowling alley. There were no other bowling alleys in town and the owner refused to serve them, preferring to keep his facility white-only.

Needless to say, this didn’t sit well with the students who were being denied their bowling entertainment. No one knows exactly who started it, but tension led to anger which led to violence, and within a few hours there were nine students and one police officer in the hospital getting treated for injuries, while other students were cared for at the college infirmary. The blows dealt by the police who’d arrived to deal with the problem were likely disproportional to whatever crimes the students had committed. Eyewitnesses claim to have seen two separate instances of “female students being held by one officer and clubbed by another.”

On that night, no one died.

Within a few days, some 200 students had amassed on the South Carolina State College campus, preparing to protest the injustice. They started a bonfire on the street in front of the campus. Firemen were called in to douse the flames, and with them came additional policemen.

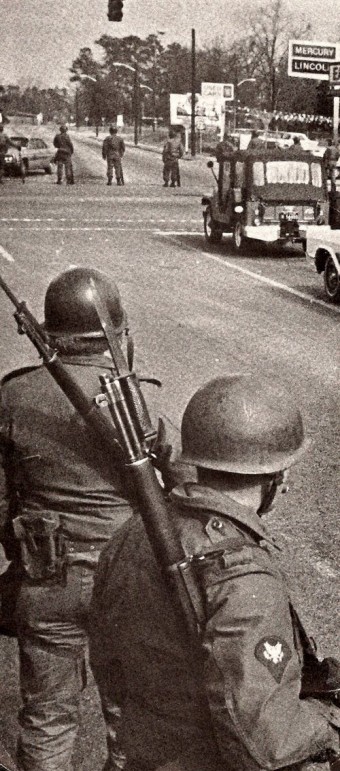

The protesting students were almost all black; the police officers were exclusively white. When they arrived bearing pistols, riot guns, and carbines, roughly 100 students retreated indoors to safety. The weapons were technically supposed to be used to disperse crowds rather than injure anyone, but given the escalation of violence at the bowling alley a few days before, students were understandably concerned.

It’s unclear exactly what happened next. Some people say that a student fired on an officer (eight police officers claimed they had fired their guns “after hearing shots”); others say that the students were all unarmed, or that a bannister rail was tossed and struck an officer. Whatever the case, one of the officers decided to fire a warning shot which prompted others to do the same. Student Robert Lee Davis recounted what happened next:

The sky lit up. Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom! And students were hollering, yelling and running. I went into a slope near the front end of the campus, and I kneeled down. I got up to run, and I took one step; that’s all I can remember. I got hit in the back.

He wasn’t the only one hit. Three students died that night: Delano Middleton, who didn’t go to the college but was visiting from a local high school; Henry Smith, an ROTC student who was shot five times; and Sam Hammond, a football player. A total of twenty-eight other students were injured. None of the police officers, save for the one that may or may not have been hit with the bannister rail, were injured.

Nine officers were put on trial in a federal court following the events, charged with “imposing summary punishment without due process of law.” However, hearing the story, the jury took all of two hours to acquit the men of their crimes. Meanwhile, Cleveland L. Sellers—program director of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—was charged with riot, conspiracy to riot and incitement to riot. He was only found guilty of the first and sentenced to a year in prison. Because of this, he was seen as the scapegoat—it was his fault for starting the riot, rather than the police officers’ fault for shooting into the crowd.

The media wasn’t helping matters. The Associated Press claimed that “a heavy exchange of gunfire” happened at the university, while local papers claimed that the black students had been sniping the police officers and throwing firebombs at the buildings. Otherwise, the incident didn’t gain a lot of attention. Civil rights leaders have criticized the lack of attention, citing the huge amount of media coverage that the Kent State Shootings received just two years later (in this case, the four students who were killed were all white).

The government has gone some way to attempt to clear the air. In 2001, then-Governor of South Carolina, Jim Hodges, addressed students at an annual memorial service at South Carolina State College. Some of the victims of the incident were present to hear him proclaim the event “a great tragedy for our state.” He also professed “deep regret.” A few years later Governor Mark Sanford added to the sentiment, saying: “I think it’s appropriate to tell the African-American community in South Carolina that we don’t just regret what happened in Orangeburg 35 years ago—we apologize for it.”

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Jane Elliot and the Blue-Eyed Children Experiment

- You Should Know About Jury Nullification

- 20 Interesting Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Facts

- The Thibodaux Massacre of 1887

- The Haun’s Mill Massacre

Bonus Facts:

- The Orangeburg Massacre was the first shooting of its kind on a United States university campus. As such, the lack of media coverage received is doubly surprising.

- The white students protesting at Kent State were protesting the Vietnam War, which may have been partially why the event received so much coverage. The war was increasingly unpopular, so the tragic deaths of students protesting what many other Americans didn’t agree with really hit home, and the media knew it would grab an audience.

- A monument has been erected on the South Carolina State University campus, and the gymnasium was named in honour of the men who died. However, Delano H. Middleton’s name was misspelled for 40 years as Delano B. Middleton, speculated to have come about because his nickname was “Bump.”

| Share the Knowledge! |

|