The Man Who Was Stuck in the 1950s

Henry Gustav Molaison, who came to be known by his initials, H.M., was studied from 1957 until his death in 2008. From an early age, H.M. suffered from severe epilepsy that was blamed on a bicycle accident when he was seven years old. He had seizures for many years that got progressively worse as he aged. The seizures finally got so bad that H.M was blacking out and could no longer work at his job assembling vehicle motors. He had to move in with his parents. At the age of 27 in 1953, H.M. was referred to neurosurgeon William Beecher Scoville at Connecticut’s Hartford Hospital.

After running out of other options, Scoville suggested an experimental surgery that would remove small parts of H.M.’s brain to reduce the seizures. Out of desperation, H.M. agreed and the surgery was performed in August 1953. It included removing most of the hippocampi (two parts of the lower brain) and portions of his temporal lobes (the side parts of the cortex); Scoville thought these areas were causing the seizures.

During the procedure, H.M. was conscious, having been given only local anesthesia. While he seemed fine during the event, as Scoville would later put it, the surgery proved to be “a tragic mistake.” Nonetheless, a mistake that would be hugely important to science, with H.M. coming to be arguably the most important individual in the history of neuroscience.

As for the seizures, the surgery was successful in that it brought them under control, but not successful in that it soon became clear it had disrupted H.M.’s memory in a debilitating way. He could remember things in the distant past, but couldn’t commit anything new to his conscious memory! H.M. could only hold onto thoughts for about 20 seconds and couldn’t recall facts he’d learned recently or events that had just happened. He could also not remember things that happened a year or two before the surgery and had random holes in his memory from the eleven years before that.

Interestingly, H.M. was able to learn new motor skills, like playing a musical instrument or a modern computer game. However, the next time he was asked to perform these activities, he had no recollection he knew how to do them, despite being able to perform well at each, something that often surprised him once he became expert at the task. H.M. also seemed to be able to acquire small pieces of information regarding public life such as the names of celebrities. He also had the ability to learn new spatial memories, like the layout of his residence, though he had no memory of how he knew this layout or what the different rooms actually looked like.

Most scientists at the time of his surgery believed memory was distributed throughout the entire brain and not dependent on any single region. H.M.’s condition revealed that there are different kinds of long-term memory that come from different parts of the brain and gave insight into what areas of the brain are responsible for converting short term memory to long term, among other things.

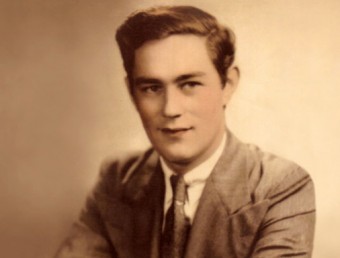

The memory loss prevented H.M. from moving forward in life. In 2004, he still thought Eisenhower was president and that he still had the full head of dark hair and unwrinkled skin he’d had in the 1950s. He lived with his parents, then a relative over the years as he couldn’t hold a job due his memory loss. During this time, H.M. would help with household duties such as shopping and yard work and proved he could perform everyday chores and tasks from what he could remember from the years before his surgery.

For the next 55 years, H.M. participated in hundreds of studies and experiments on memory and learning, revealing previously unknown information about the workings of the human brain. Despite his amnesia, H.M.’s intelligence in areas outside of memory remained normal and he continued to have a normal IQ. This made him an excellent candidate for experiments. The damage to his brain also did not change his personality. This made him somewhat ideal to work with because he was a very friendly and happy individual, even telling jokes. He also never tired of doing memory tests repeatedly that others would find tedious; after all, they were new to him every time. Between testing, H.M. would often do crossword puzzles. If the words were erased, he would do the same ones over and over again.

As for how he felt about all this, he once stated,

I’m having a little argument with myself. Right now, I’m wondering. Have I done or said anything amiss? You see, at this moment everything looks clear to me, but what happened just before? That’s what worries me.

H.M. lived in a nursing home from the time he was 54-years-old until he died in 2008 at the age of 82. He left his body to science and, following his death, his brain was dissected into 2401 “slices” at the UC San Diego. Imaging of it showed that damage was more widespread than previously thought, making it hard to identify a specific fine-grained area or areas that were responsible for his memory loss. Nonetheless, the research on his brain is ongoing and continues to be extremely important in our understanding of how the memory systems of the brain work.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- There are People Who Can’t “See” Faces

- Goldfish Do Not Have a Three Second Memory

- Elephants Really Do Have Exceptionally Good Memories

- How Deaf People Think

- You Actually Use All of Your Brain, Not 10%

Bonus Facts:

- H.M. has been mentioned in almost 12,000 medical reports or articles. This large number makes him the most studied case person in psychological or medical history.

- It was only after his death that H.M.’s identity was revealed to the public. Until then he was known by his initials to protect his privacy.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Check also into Clive Waring, esp. for notes on difference between episodic and procedural memory. How does “working” memory relate to those two and to long-term. “muscle”, and short-term memory? i confuse these things.