The Revenge of Han van Meegeren, One of the Great Art Forgers of All Time

Today I found out about Han van Meegeren, the great art forger.

Today I found out about Han van Meegeren, the great art forger.

Han van Meegeren was born in 1889 and developed an interest in painting at a young age. He wasn’t supported in his dream to become an artist by his father, who forbade van Meegeren’s artistic development, trying to steer his son in the direction of architecture instead. Undeterred, van Meegeren met Bartus Kortelling—a teacher and painter—at his school, and Kortelling later became van Meegeren’s mentor.

Kortelling loved paintings from the Dutch Golden Age and likely had a hand in van Meegeren’s love of golden age paintings as well. A particular fan of Johannes Vermeer, Kortelling showed his protégé how Vermeer mixed his colours—a lesson that would have a great impact on the aspiring artist’s later life.

Still, van Meegeren’s father was not impressed. He sent his son to school in Delft to become an architect. Perhaps he wasn’t aware, but Delft was the one-time hometown of Vermeer. Van Meegeren proved to be an adept architect, but his heart was still set on painting. He continued his painting lessons and never took the final exam that would allow him to become an architect. Instead, he moved on to art school in The Hague in 1913. That same year, he was granted a Gold Medal from his school in Delft for his painting The Study of the Interior of the Church of Saint Lawrence.

Van Meegeren exhibited his first set of legitimate paintings in 1917, and they proved to be quite popular among critics. However, as time went on he garnered less and less attention. Critics were more interested in the forward-thinking artists like the Cubists and Surrealists; they remarked that van Meegeren had little to offer because he was focused only on the past. He received comments about being unoriginal and simply “a copycat” without as much talent as the great artists who had lived before him.

In 1945, van Meegeren declared,

Driven into a state of anxiety and depression due to the all-too-meager appreciation of my work, I decided, one fateful day, to revenge myself on the art critics and experts by doing something the likes of which the world had never seen before.

That “something” happened to be “the perfect forgery.” Van Meegeren set out to show the world that he was just as good as the old artists by creating paintings and passing them off as the old artists’ originals—and make a lot of money doing it.

It was easy for him to settle on Vermeer. He already had a base knowledge of Vermeer from his mentor, and Vermeer was a good target because he’d only produced around 35 paintings—just a tenth of his contemporaries’ output. That meant art historians were constantly on the lookout for undiscovered Vermeers. The thought that there should be more likely made it easier for them to believe that they saw a new one when they were presented with one—even if it was a forgery.

Van Meegeren was a careful forger. He did extensive research on Vermeer and his paintings, bought authentic 17th-century canvasses, and used the original formulas for making his own paints. His biggest problem was trying to make the painting look like it was 300 years old. Oil paint takes decades to dry completely, which meant that a newer painting would be found out the moment someone touched it. He was forced to experiment with the original paint formulas and baking his paintings in an oven. Most of the paints burned or melted, but he found using phenol formaldehyde on a finished painting would make the paint harden. When it was finished baking, he would roll a cylinder over it to make more cracks, making it look more legitimate.

Once the process of creating old-looking paintings was perfected, van Meegeren had another obstacle: the content of the paintings. At first, he painted pictures much like those that Vermeer had painted, but he found that experts looked too closely at them and detected little differences between the real thing and the forgery. He ended up taking a gamble and painting something completely different than what Vermeer painted, but with hints of Vermeer’s style.

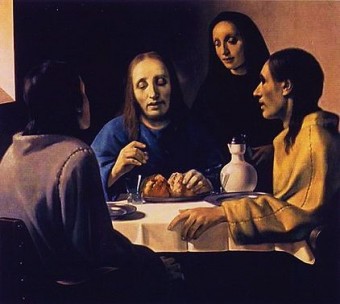

The result? Millions of dollars straight into van Meegeren’s pockets. It was his famous “Christ at Emmaus” painting that allowed van Meegeren to break into the market. The painting was larger than anything Vermeer had done, and it had religious subject matter, which was also different. But art historians had speculated that Vermeer had painted something like “Christ at Emmaus” for some time, and they were eager to believe that the painting really was Vermeer’s.

He even fooled Abraham Bredius, an art historian who had a reputation for authenticating new Vermeers. The historian wrote an article on “Christ at Emmaus,” saying,

It is a wonderful moment in the life of a lover of art when he finds himself suddenly confronted with a hitherto unknown painting by a great master, untouched, on the original canvas, and without any restoration, just as it left the painter’s studio! And what a picture! … I am inclined to say the masterpiece of Johannes Vermeer of Delft…

Van Meegeren continued to churn out paintings with religious subject matter, and they continued to be snapped up by art enthusiasts. By the time he was found out, he’d made $30 million on his forgeries (about $400 million today). Unfortunately, his incredible success ended up being his undoing.

During World War II, Hermann Goerring—“the No. 2 man in Nazi Germany”—traded 137 paintings for van Meegeren’s forgery “Christ with the Woman Taken in Adultery.” Unfortunately for van Meegeren, Goerring kept meticulous papers regarding his transactions. At the end of World War II, van Meegeren’s name was found next to the trade for the Vermeer, and he was arrested in 1945 for “collaborating with the enemy.”

The allegations might have carried a death sentence, and so van Meegeren was forced to out himself as a forger. He claimed responsibility for the painting of the Vermeer that Goerring had bought, along with five other Vermeer paintings and two Pieter de Hooghs, all of which had been “discovered” after 1937. The astonished court room had him paint another forgery in front of them to prove it, and when he passed the test his charges were changed to forgery and he was sentenced to just one year in prison, which was the minimum prison sentence for such a crime.

Rather than be angry with van Meegeren, the Dutch public largely lauded him as a hero. During his trial, he presented himself as a patriot—he had, after all, secured 137 paintings that had been unlawfully seized by Goerring by duping the famous Nazi into thinking he’d purchased a real Vermeer. As van Meegeren said, “How could a person demonstrate his patriotism, his love of Holland more than I did by conning the great enemy of the Dutch people?”

Van Meegeren never served his one year in prison. He died of a heart attack two months after his two-year trial. Until the end, he believed that—when he was gone—his name would soon be forgotten, and his paintings would eventually be remembered as true Vermeers.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Monkey Artist Hoax

- The Origin of “Where’s Waldo”

- How an Etch A Sketch Works

- The Novel ‘Gadsby’ has 50,110 Words In It, None of Which Contain the Letter ‘E’

- Joseph Pujol, World Famous Farter

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

How can there be 4 comments when there are no comments.