The Voynich Manuscript

So mysterious, no one even knows exactly which century it was written in, the Voynich Manuscript has stumped medieval scholars, linguists, cryptologists and the curious for hundreds of years.

So mysterious, no one even knows exactly which century it was written in, the Voynich Manuscript has stumped medieval scholars, linguists, cryptologists and the curious for hundreds of years.

The Manuscript

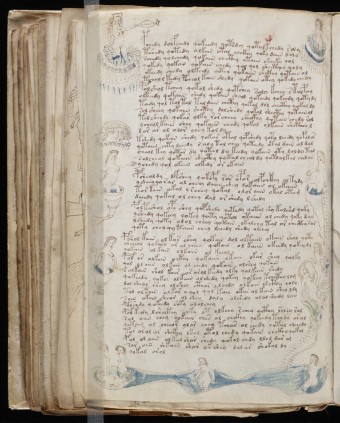

Approximately 6″ x 9″ x 2″, this octavo contains 240 pages of indecipherable text and a host of illustrations drawn with iron gall ink on vellum. Many of the pages are folios that fold out for full display. It is bound, also in vellum, although experts believe the cover was added after the original manuscript was written. It is possible that the color in the illustrations was added later, as well.

Other than that, it is difficult to describe the Voynich – you really have to see it. There is writing throughout the book in an unknown, yet seemingly simple, script accompanied by illustrations. But these are no ordinary drawings.

The curators at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, where the book is housed, have divided the illustrations into six categories:

- “Star-like flowers” in the margins of pages filled otherwise with text.

- Drawings of known medicinal herbs and roots (over 100 different kinds) are shown in jars or other vessels.

- Nine cosmological medallions are arranged across several of the folded folios.

- Naked ladies, possibly pregnant, often in liquid and connected to the fluid or each other by tubes or pipes (the tactful curators call this the biological section).

- Astronomical and astrological drawings including several of the signs of the Zodiac, radiating circles, astronomical bodies, astral charts and more naked ladies.

- Over 100 unidentified plant species.

Despite exhaustive efforts by people across the globe to decipher the text, no one knows who wrote the manuscript, when, where or even why.

Known History

Although some insist that radiocarbon dating and analysis of the inks used on the book demonstrate that it was written in the early 1400s, the Beinecke does not limit its possible copyright date more than sometime between “the end of the 15th or during the 16th century.”

The tale of what is known of the book’s provenance is best told out of chronological order:

The first records of the book come in letters written to the distinguished polymath and decipherer of hieroglyphics, Athanasius Kircher. In 1639, Georg Baresch wrote to Kircher about the manuscript; later, it is believed that, at his death, Baresch left the Voynich to the well-respected doctor, Jan Marek Marci. Marci wrote to Kircher, in a letter that was delivered along with the book, in 1666, noting that, among other things, the book had been owned by the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II sometime between 1552 and 1612.

Rudolf, who loved science, nature and art, kept great thinkers like Erasmus and scientists like Johannes Kepler and Tycho Brahe in his court. Open also to different ideas, he would sponsor dubious people, like the alchemist Edward Kelley and the astrologer John Dee.

According to some reports, Kelley (or Dee) brought the book to Rudolf’s court, claiming the manuscript had been written by Roger Bacon, the 13th century experimental scientist with a reputation for dealing in alchemy, although there is no proof for that. In any event, Kelley (or Dee) is reported to have sold the book to Rudolf for an amount that in today’s dollars would be about $100,000.

Rudolf in turn is reported to have given the manuscript to his physician and head gardener, Jacobus Horcicky de Tepenec (also known as Jacobus Sinapius), a transfer that is recorded on the book, but only legible when read with ultraviolet light. Jacobus died in 1622, and It is uncertain when or how Baresch obtained the text.

In any event, after the 1666 letter to Kircher, the book disappeared for 250 years, only to resurface again in 1912 when Wilfrid Voynich bought it, along with 30 other manuscripts, from the Jesuit Collegio Romano. Scholars believe the Jesuits had acquired Kircher’s library after his death, and that the book sat in obscurity during the interim.

Voynich did little with the manuscript, and upon his widow’s death in 1960, her friend, Anne Nill, inherited it; a capitalist, Nill sold the manuscript to Hans P. Kraus in 1961. Kraus gave up trying to sell a book no one could read and donated it to Yale University in 1969. It currently resides there, in the Beinecke Library.

Authorship Theories

Over the years, several theories, but no definitive answers, have been proposed as to who wrote the manuscript.

Both Marci and Wilfrid Voynich thought the book was written by Roger Bacon in the 13th century; this has never been confirmed, and most date the origins of the book to well-after Bacon’s death.

It has been suggested that Rudolf’s doctor, Jacobus, who was also a noted botanist, wrote the manuscript; this has been discredited by the discovery of his verified signature, which does not match the writing in the book.

Another proposed author was the diplomat, lawyer and cryptographer, Raphael Sobiehrd-Mnishovsky. It is rumored that he claimed to have written an indecipherable code long before Baresch wrote to Kircher, and he was friends with Marci; in fact, he is credited with telling him the story of how Rudolf came by the manuscript.

The Renaissance architect, Antonio Averlino, has also been suggested as a possible author. This theory holds that Averlino prepared the manuscript as a way to sneak otherwise banned scientific content into Constantinople.

Contrarily, some believe it was a hoax. Many have been accused, including both Dee and Kelley; notably, Edward Kelley had been found guilty of forgery at one time and had his ears cut off. It has also been proposed that Marci fabricated the manuscript, and ensnared Kircher, as part of an academic/political war that had been raging between more secular-minded scholars and the Catholic Church at the time. Others think Voynich forged the manuscript. As a rare book dealer, he had access to ancient vellum and ink and could easily have written the script.

Recent Developments

In 2013, after an exhaustive analysis of linguistic patterns in the manuscript, scholars determined that, given the text’s organizational structure and the frequency and location of both content-bearing and structural and functional words, the Voynich is likely not a hoax. As the authors noted, “While the mystery of origins and meaning of the text remain to be solved, the accumulated evidence about organization at different levels, limits severely the scope of the hoax hypothesis and suggests the presence of a genuine linguistic structure.”

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Mystery of the Gobekli Tepe

- The Mysterious Fate of the Library at Alexandria

- Why the Dodo Went Extinct

- The Mystery of the Mary Celeste

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

I love books and this one is really interesting. Here is another rare book.

—————————————————-

The Gutenberg Bible:

The Gutenberg Bible (also known as 42-line Bible, the Mazarin Bible or the B42) was the first major book printed with movable type in the West. It marked the start of the “Gutenberg Revolution” and the age of the printed book in the West. Widely praised for its high aesthetic and artistic qualities, the book has an iconic status. Written in Latin, the Gutenberg Bible is an edition of the Vulgate, printed by Johannes Gutenberg, in Mainz, Germany, in the 1450s. Forty-eight copies, or substantial portions of copies, survive, and they are considered to be among the most valuable books in the world, even though a complete copy has not been sold since 1978. The 36-line Bible, believed to be the second printed version of the Bible, is also sometimes referred to as a Gutenberg Bible, but is likely the work of another printer.

—————————————————-

Early owners:

The Bible seems to have sold out immediately, with initial sales to owners as far away as England and possibly Sweden and Hungary. At least some copies are known to have sold for 30 florins – about three years wages for a clerk. Although this made them significantly cheaper than manuscript Bibles, most students, priests or other people of ordinary income would have been unable to afford them. It is assumed that most were sold to monasteries, universities and particularly wealthy individuals. At present only one copy is known to have been privately owned in the fifteenth century. Some are known to have been used for communal readings in monastery refectories; others may have been for display rather than use, and a few were certainly used for study. Kristian Jensen suggests that many copies were bought by wealthy and pious laypeople for donation to religious institutions.

Influence on later Bibles

The Gutenberg Bible had an incalculable effect on the history of the printed book. Textually, it also had an influence on future editions of the Bible. It provided the model for several later editions, including the 36 Line Bible, Mentelin’s Latin Bible, and the first and third Eggestein Bibles. The third Eggestein Bible was set from the copy of the Gutenberg Bible now in Cambridge University Library. The Gutenberg Bible also had an influence on the Clementine edition of the Vulgate commissioned by the Papacy in the late sixteenth century.

———————————————————-

Recent history:

Today, few copies remain in religious institutions, with most now owned by university libraries and other major scholarly institutions. After centuries in which all copies seem to have remained in Europe, the first Gutenberg Bible reached North America in 1847. It is now in the New York Public Library. In the last hundred years, several long-lost copies have come to light, and our understanding of how the Bible was produced and distributed has improved considerably.The only copy held outside Europe or North America is the first volume of a Gutenberg Bible (Hubay 45) at Keio University in Tokyo. The HUMI Project team at Keio University is known for its high-quality digital images of Gutenberg Bibles and other rare books.

In 1921 a New York book dealer, Gabriel Wells, bought a damaged paper copy, dismantled the book and sold sections and individual leaves to book collectors and libraries. The leaves were sold in a portfolio case with an essay written by A. Edward Newton, and were referred to as “Noble Fragments”. In 1953 Charles Scribner’s Sons, also book dealers in New York, dismembered a paper copy of volume II. The largest portion of this, the New Testament, is now owned by Indiana University.

The matching first volume of this copy was subsequently discovered in Mons, Belgium. The last sale of a complete Gutenberg Bible took place in 1978. It fetched $2.2 million. This copy is now in Stuttgart. The price of a complete copy today is estimated at $25−35 million. Individual leaves now sell for $20,000–$100,000, depending upon condition and the desirability of the page.

——————————————————–

I suspect that there are many rare books in the Vatican archives and some of these are the books that were banned

the Voynich manuscript is originally just one of the many books from the vedic time and one of the vedas thats why they cannot be understood and deciphered by todays so called experts assomeone with knowledge of ancient india and a thourough understanding of the vedas which may take years to understand might realise this text of the vedic times. the drawings and carricatures of plants are of those plants and trees and herbs foundand existed in the region of ancient india known as BHARAT or aryavarta.

these ancient texts were a part of the huge collection storedat the nalanda university,the library of alexandria ANDand other places of studyon earth which was over the time,looted and plundered by the muslims and the christians THIS PARTICULAR TEXT WAS WRITTEN BY DHANVANTARI AND MEANT FOR STUDY for the benefit of allmankind. there were thousands of such texts written during the period of vedic india written by rishis munis and scholars of those times they were a priceless gift to humans and mankind by the hindu religion the devas and the ancient aliens of vedic india . all the plants in this book can still be found in the region of india

Good day!

I have been deciphering the Voynich manuscript and obtained concrete results.

The Voynich manuscript is not written with letters. It is written in signs. Characters replace the letters of the alphabet one of the ancient language. Moreover, in the text there are 2 levels of encryption. I figured out the key by which the first section could read the following words: hemp, wearing hemp; food, food (sheet 20 at the numbering on the Internet); to clean (gut), knowledge, perhaps the desire, to drink, sweet beverage (nectar), maturation (maturity), to consider, to believe (sheet 107); to drink; six; flourishing; increasing; intense; peas; sweet drink, nectar, etc. Is just the short words, 2-3 sign. To translate words with more than 2-3 characters requires knowledge of this ancient language. The fact that some symbols represent two letters. In the end, the word consisting of three characters can fit up to six letters. Three letters are superfluous. In the end, you need six characters to define the semantic word of three letters. Of course, without knowledge of this language make it very difficult even with a dictionary.

If you are interested, I am ready to send more detailed information, including scans of pages showing the translated words.

Nicholai.