How Hieroglyphics were Originally Translated

Today I found out about the history of the Rosetta Stone and how hieroglyphics were first translated.

Today I found out about the history of the Rosetta Stone and how hieroglyphics were first translated.

Hieroglyphics were elaborate, elegant symbols used prolifically in Ancient Egypt. The symbols decorated temples and tombs of pharaohs. However, being quite ornate, other scripts were usually used in day-to-day life, such as demotic, a precursor to Coptic, which was used in Egypt until the 1000s. These other scripts were sort of like different hieroglyphic fonts—your classic Times New Roman to Jokerman or Vivaldi.

Unfortunately, hieroglyphics started to disappear. Christianity was becoming more and more popular, and around 400 A.D. hieroglyphics were outlawed in order to break from the tradition of Egypt’s “pagan” past. The last dated hieroglyph was carved in a temple on the island of Philae in 395 A.D. Coptic was then written and spoken—a combination of twenty-four Greek characters and six demotic characters—before the spread of Arabic meant that Egypt was cut off from the last connection to its linguistic past.

What remained were temples and monuments covered in hieroglyphic writing and no knowledge about how to begin translating them. Scientists and historians who analyzed the symbols in the next few centuries believed that it was a form of ancient picture writing. Thus, instead of translating the symbols phonetically—that is, representing sounds—they translated them literally based on the image they saw.

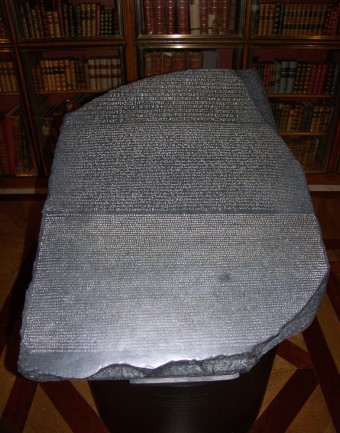

It wasn’t until July 19, 1799 when a breakthrough in translation was discovered by French soldiers building an extension on a fort in el-Rashid, or Rosetta, under the orders of Napoleon Bonaparte. While demolishing an ancient wall, they discovered a large slab of granodiorite bearing an inscription in three different scripts. Before the French had much of a chance to examine it, however, the stone was handed over to the British in 1802 following the Treaty of Capitulation.

On this stone, known as the Rosetta Stone, the three scripts present were hieroglyphics, demotic, and Greek. Soon after arriving at the British Museum, the Greek translation revealed that the inscription is a decree by Ptolemy V, issued in 196 B.C. in Memphis. One of the most important lines of the decree is this stipulation laid down by Ptolemy V: “and the decree should be written on a stela of hard stone, in sacred writing, document writing, and Greek writing.” The “sacred writing” was hieroglyphics and “document writing” referred to demotic—this confirmed that the inscription was the same message three times over, providing a way to begin translating hieroglyphics at last!

One of the big problems encountered was that they could try to translate written text all they wanted, but it wouldn’t give the translators an idea of the sounds made when the text was spoken. In 1814, Thomas Young discovered a series of hieroglyphs surrounded by a loop, called a cartouche. The cartouche signified something important, which Young hypothesized could be the name of something significant—kind of like capitalizing a proper noun. If it was a pharoah’s name, then the sound would be relatively similar to the way the names are commonly pronounced in numerous other languages where we know the pronunciation.

However, Young was still working under the delusion that hieroglyphs were picture writing, which ultimately caused him to abandon his work which he called “the amusement of a few leisure hours”, even though he had managed to successfully correlate many hieroglyphs with their phonetic values.

A few years later, Jean-Francois Champollion finally cracked the code in 1822. Champollion had a long-time obsession with hieroglyphics and Egyptian culture. He’d even become fluent in Coptic, though it had long since become a dead language. Using Young’s theory and focusing on cartouches, he found one containing four hieroglyphs, the last two of which were known to represent an “s” sound. The first one was a circle with a large black dot in the centre, which he thought might represent the sun. He dug into his knowledge of the Coptic language, which he hadn’t previously considered to be part of the equation, and knew that “ra” meant “sun.” Therefore, the word that fit was the pharaoh Ramses and the connection between Coptic and hieroglyphics was now perfectly clear.

Champollion’s research provided the momentum to get the ball rolling on hieroglyphic translation. He now demonstrated conclusively that hieroglyphics weren’t just picture writing, but a phonetic language. Champollion went on to translate hieroglyphic text in the temples in Egypt, making notes about his translations along the way. He discovered the phonetic value of most hieroglyphs. It was a good thing he kept extensive notes, too as he suffered a stroke three years later and died at the age of 41. Without those notes, much of the progress made on the translations would have been lost.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- A Man Once Tried to Raise His Son as a Native Speaker in Klingon

- What E Pluribus Unum Means

- How Dick Came to Be Short for Richard

- The Word Dinner Used to Mean Breakfast

- How the Adam’s Apple Came to be Called That

Bonus Facts:

- The Rosetta Stone now sits in the British Museum, where it’s been since 1801.

- The Rosetta Stone is commonly thought to be made of black basalt due to its dark hue. This is incorrect—the dark colour is actually due to a layer of carnauba wax which was put on the stone to protect it from oil on people’s fingers as they were examining the text.

- There is no single translation of the decree inscribed upon the Rosetta Stone because of minor differences in the text as well as a still-developing understanding of the language, but a version of the translation can be found on the British Museum’s website.

- Roughly 45 inches high, 28.5 inches wide, and 11 inches thick, the Rosetta Stone weighs over 1700 pounds. Still, the stone isn’t complete. Many of the lines of text are broken or completely absent. Unfortunately, the rest of the stone has been lost to time.

- The stone was only moved from display at the British Museum twice. At the end of World War I, museum workers feared for the stone’s safety due to bombing in London. It was moved to a station 50 feet below the ground in Holborn and stayed there for two years. In 1972, it was moved to the Lourve in Paris to be displayed alongside Champollion’s Lettre, describing the translation of hieroglyphs, on its 150th anniversary of publication.

- In 1802, plaster casts of the inscriptions were made and sent to the universities of Edinburgh, Oxford, and Cambridge, as well as Trinity College Dublin.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Louvre.

I am from Bougainville Island, the eastern most province in Papua New Guinea. Just yesterday the 10th of July 2016 a group of locals excavated a stone with engravings if the sun and moon as well as other drawings. It is unbelievable this hieroglyphics could be found in this place where the primitive people were only discovered by white men a mere 100 years ago. It would be interesting for historians as to how these engravings ended on this Island given the fact that the people are black in skin colour and most of these hieroglyphics is found on places where the people a white skinned colour. Can someone help please? I will post some photos of the engravings in my next post if someone now shows interest.